Journal of Financial Planning: December 2016

Sonya L. Britt, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of personal financial planning at Kansas State University. She is co-editor of Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice and Student Financial Literacy: Campus-Based Program Development. Her educational background is in therapy and financial planning from Kansas State University and Texas Tech University.

Derek R. Lawson, CFP®, is a doctoral student in personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Prior to attending Kansas State, he was a financial planner in Kansas City. He currently serves as treasurer of the Financial Therapy Association and sits on several committees and boards for other national professional organizations.

Camila A. Haselwood is an admissions specialist for the Kansas State University Graduate School. She is currently a doctoral student in personal financial planning and a peer financial counselor and student advisory board member for Powercat Financial Counseling at Kansas State University.

Executive Summary

- This article is a primer on assessing physiological stress in the financial planning office. Planners will understand the implications of stress on immediate-term likelihood of motivation in clients.

- Results of the analyses reveal that being relaxed is associated with an increased readiness to change.

- The InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (Prawitz et al. 2006) is an assessment of eight questions, and it may be useful in helping financial planners analyze their client’s perceived financial stress level. Higher scores indicate less financial stress, and lower scores indicate higher financial stress.

- Physiological stress can be assessed by observing clients’ behavior. Cold hands, absent-mindedness, and fidgeting may indicate elevated levels of physiological stress.

Stress can hinder rational decision making—a key assumption of financial planning. Decisions made under stress tend to be based on habit, instinct, or emotions, and are present-oriented in nature (Pham 2007). Memory recall is also negatively affected by stress (Oei, Everaerd, Elzinga, Van Well, and Bermond 2006). And there is some indication of a correlation between personality and stress (Zellars, Meurs, Perrewe, Kacmar, and Rossi 2009), specifically physiological stress, which measures internal reactions to stressful events by use of blood pressure, skin temperature, and sweat production. According to Zellars et al., individuals who rated high in negative affectivity (i.e., were more susceptible to negative emotions, such as anger, fear, and anxiety) tended to have higher initial stress levels and recovered more slowly from stressful events compared to individuals who were low in negative affectivity (i.e., experienced less frequent negative emotions).

The purpose of this study was to expand our knowledge of the role of physiological stress in the financial planning process by exploring the influence of physiological stress on financial goal achievement.

Individuals under stress are hypothesized to have emotional or memory blocks that prevent them from making progress on their financial goals, which may be the reason why planners have difficulty with client follow-through. Financial planners have commonly expressed difficulty getting some clients to follow through on tasks. Planners may spend hours preparing a plan that is ultimately never taken off the bookshelf. Stress may be a key factor in the reason why clients are not following through. It has been suggested that stressed clients will not be able to fully comprehend the implications of implementing or failing to implement recommendations (Grable and Britt 2012), although this assertion has gone untested. It is possible that a certain level of stress (or motivation) is necessary to encourage change. By and large, it is advantageous for clients to be in a relaxed state of mind for financial planning. This study tested Grable and Britt’s (2012) assertion by following individuals over a three-month period to evaluate progress on goals based on physiological stress levels during the initial financial planning meeting. Results indicate that physiological stress did, in fact, obstruct the financial planning process.

Conceptual Background

From a transtheoretical model of change (TTM) perspective, individuals must be in a change state of mind before any action will occur (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983). Individuals progress, not necessarily linearly, but rather through five stages of change: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Termination is sometimes considered a sixth stage, although financial planning tends to be ongoing.

Pre-contemplation indicates that an individual is not considering a change in behavior in the next six months. A financial planner would be unlikely to see these individuals as clients because the person sees that there is no problem or need for change. Other professionals may encounter individuals in the pre-contemplation stage if the help-seeking is court mandated (as may be the case in substance abuse or domestic violence), or if one partner in a relationship is coerced into coming with a partner further along in the change process.

The contemplation stage indicates that the individual has acknowledged that change is needed and is thinking about changing. Individuals in the contemplation stage have expressed that they may need to make changes in terms of their financial situation. These individuals have done research on financial topics but have not completely committed to whether or not they want to change (Horwitz and Klontz 2013). According to Miller and Rollnick (1992), individuals in this stage are not ready for advice on financial topics from counselors, and if advice is given prematurely, it may cause the individual to resist. Individuals in the contemplation stage intend to take action within the next six months (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983; Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross 1992). As with the pre-contemplation stage, these individuals are unlikely to be clients. They could, however, be influenced by marketing strategies designed to encourage them to seek help.

Individuals in the preparation stage are getting ready to make changes to their behavior. An individual in this stage will prepare to change his or her habits by seeking information from professionals (Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente 1994). During the preparation stage, individuals may be preparing to cut wasteful spending, pay down debt, and begin saving (Horwitz and Klontz 2013). According to Prochaska et al. (1994) during the preparation stage individuals will need the most support because they realize it will be difficult and the chances of success are slim. Even though an individual may have feelings of not succeeding, the preparation stage is where the action plan is created and built to move toward a solution (Horwitz and Klontz 2013). According to Kerkmann (1998), individuals in the preparation stage are willing to change within the next 30 days.

Individuals in the action stage have taken measures to change their behavior and have been making changes for less than six months. According to Horwitz and Klontz (2013), the action stage is where real change occurs. Bad habits start to transition to healthier habits, and other people begin to see the changes that are being made (Prochaska et al. 1994). The action stage is where an individual has decided to take the time and energy to commit to solving their financial problems (Kerkmann 1998). The excitement of the initial plan may be wearing off and individuals may realize that the action stage is going to take consistent work (Prochaska et al. 1994). Individuals in the action stage need to believe they can accomplish the plan to help fight a relapse (Prochaska et al. 1994). The majority of financial planning and counseling clients are likely to be in the action stage, because they are seeking and eagerly wanting the financial help.

The maintenance stage indicates that individuals have been making changes for six to 18 months (Xiao and Wu 2006). The goal of the maintenance stage is to reduce and prevent behavior lapses (Prochaska et al. 1994). Financial planners tend to do this by having quarterly, semi-annual, and/or annual meetings with clients. The transtheoretical model of change has the potential to be used by financial planners to help improve services and assist in changing behaviors (Xiao and Wu 2006).

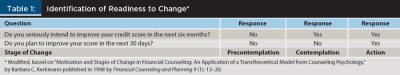

Prochaska et al. (1992) developed a matrix to identify which readiness to change stage the client may be experiencing based on two questions: (1) Do you seriously intend to improve your credit score (or substitute another behavior here) in the next six months? and (2) Do you plan to improve your credit score (or substituted behavior) in the next 30 days?

As shown in Table 1, clients who respond negatively to both questions are not willing to acknowledge that change is needed. Clients who respond affirmatively to the first question, but negatively to the second question are contemplating change. And clients who respond positively to both questions are in the action stage (Prochaska et al. 1992).

Hypotheses

To determine how physiological stress influenced intentions/readiness to change and actual change, individuals needed to identify one or more financial goals. To keep the design consistent across respondents, the research team self-imposed the goal of increasing one’s credit score within the next three months. Respondents were asked to indicate other financial goals that they wanted to make progress on over the next three months. Credit issues can affect individuals of all income levels, making it a good goal to track for a research study.

Based on the TTM framework, individuals must be in a change state of mind before any progress can be made (i.e., intentions proceed behavior change). Physiological stress blocks future-orientations of individuals; therefore, it was assumed that respondents with elevated levels of physiological stress would have low intentions to change their behavior and make little to no progress in changing their behavior.

H1: Lower levels of physiological stress are associated with greater intentions of changing.

H2: Lower levels of physiological stress are associated with greater goal progress.

Methodology

Sample. Initial data was collected from August 2014 to December 2014 with follow-up surveys ending in March 2015. Respondents were recruited from a Midwestern community with a population of approximately 52,000 by use of social media and a daily email announcement sent to a large employer in the community.

The advertisement read: “Have credit questions? Are you interested in what your credit score is? Are you married or living with a significant other? Sign up for a one-hour financial counseling session.” And the principal investigator’s contact information provided. The use of this advertisement likely attracted individuals with lower credit scores who would not otherwise have been seeking financial counseling or planning. Respondents were not charged a fee for attending the meeting and were not provided with an incentive for participating.

To participate in the study, respondents had to be married or living with a significant other (all couples were heterosexual) to control for marital status within the small sample. Respondents did not receive ongoing financial counseling or planning services past their engagement in this research study. Eighteen respondents (nine couples) met with the financial counselor jointly as a couple, and nine respondents (two couples and five individuals whose partner did not complete an individual meeting) met with the financial counselor individually for a final sample size of 27. The financial counselor was the same for all respondents and the content (credit score improvement) was the same for each meeting.

The majority of respondents were white (89 percent) and the remaining 11 percent were black (no other ethnic populations were represented), which is fairly representative of the population in which the respondents were recruited (84 percent white, 6 percent black). Eighty-one percent of the respondents were married, while the remaining 19 percent were unmarried but cohabitating. More than half (56 percent) of the sample had no children, whereas 22 percent had one child and another 22 percent had two children. The average respondent age was 28 ranging from ages 18 to 59. Average net household income was $55,747 with a range of $40,680 to $88,800. Four percent of the sample had a high school education, 22 percent had completed some college, 33 percent had a college degree, 19 percent had completed some graduate school, and 22 percent had completed a graduate degree.

Variables. Respondents completed a two-page paper survey at the beginning of the one-hour meeting. In addition to demographic data, respondents were asked to self-assess their level of financial satisfaction, perceived financial stress, and financial knowledge on a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 indicated very dissatisfied/stressed/low knowledge and 10 indicated very satisfied/not at all stressed/very knowledgeable. The survey also assessed for frequency of viewing one’s credit score, objective financial knowledge, and financial behavior. It is important to note that self-reported measures may not be accurate representations of actual status or behaviors.

Throughout the duration of the one-hour meeting, the respondents’ non-dominant fingers were connected to the Thought Technology ProComp Infiniti Encoder to gather physiological data. Physiological stress was proxied by the skin temperature reading. Reductions in temperature at distal skin locations, such as the fingertip, have been found to be associated with increased stress exposure (Vinkers et al. 2013). During stressful situations, blood pressure rises and blood volume to distal skin locations decreases as blood rushes to the heart to prepare for the fight or flight response. The result is less blood flow to distal locations, such as the fingertips and the accompanying colder hands (Wofford 2001). The Thought Technology temperature sensor measures skin temperature between 50 and 115 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the manufacturer’s website. It’s important to note, there are no clearly established cut-off scores/skin temperatures for what constitutes a stressed individual versus a relaxed individual.

Respondents were asked to pull their initial credit score from Credit Karma (www.creditkarma.com) prior to their meeting. At the end of the meeting, respondents were asked to indicate if they planned to make improvements to their credit score (the self-imposed financial planning goal) at the end of six months and at the end of 30 days.

Respondents were sent electronic surveys via Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com) two weeks, one month, two months, and three months after their initial meeting.

The two-week and one-month surveys asked respondents to indicate how frequently they had thought about their goals since the meeting where 1 = not at all; 2 = once or twice; 3 = at least every few days; 4 = almost every day; and 5 = every day.

Respondents were also asked to evaluate their progress toward their financial goals since the last meeting where 1 = no progress; 2 = slight progress; 3 = moderate progress; 4 = extreme progress; and 5 = goal accomplished.

Finally, two yes/no questions were asked: (1) Do you seriously intend to improve your credit score in the next six months? and (2) Do you plan to improve your credit score in the next 30 days?

The two-month survey was a combined version of the initial survey and a shorter follow-up survey. The three-month survey contained just one item: “Please go to www.creditkarma.com to access your credit score. Please indicate your three-digit credit score.”

Analysis. Data analysis was limited to bivariate statistics (means and correlations) due to the small sample size. Other physiological stress studies have also reported small sample sizes of eight to 30 respondents (Causse, Baracat, Pastor, and Dehais 2011; Lo and Repin 2002; Oei et al. 2006).

Results: Intentions/Readiness to Change

To test Hypothesis 1—lower levels of physiological stress are associated with intentions of changing—skin temperature was used as a proxy for physiological stress and forward progress in the TTM stages of change as illustrated in Table 1. A respondent’s average skin temperature (i.e., lower physiological stress) was positively correlated with forward readiness to change between the initial meeting and two weeks post-meeting (r = .49, p < .05) and two months post-meeting (r = .58, p < .01). In other words, respondents who were in a more relaxed state during their financial counseling meeting were more likely to report positive progress on their readiness to change. This included respondents who may have moved from pre-contemplation to contemplation or from contemplation to action stages (among other possibilities).

Tables 2 and 3 show the average skin temperature of respondents who (1) regressed in their readiness to change (M = 76.59; M = 71.59); (2) remained in the same TTM stage (M = 80.53; M = 82.39); and (3) progressed in their readiness to change (M = 86.07; M = 85.00) between the initial meeting and the two-week follow-up survey and two-month follow-up survey, respectively.

Results show a general increase in average skin temperature (lower level of stress) between respondents who made negative change, no change, and positive change. Respondents who regressed in their readiness to change after two months reported the highest stress as measured by the lowest skin temperature at the initial meeting. Respondents who reported intentions of changing after two weeks and two months yielded the lowest level of physiological stress (highest skin temperature), providing support for Hypothesis 1.

Results: Goal Progress

Hypothesis 2 stated that lower levels of physiological stress would be associated with goal progress as measured by self-reported progress on goals and actual change in credit score. One respondent reported a credit score of 350 at the initial meeting and 700 at the three-month follow-up. It seemed unlikely that the score would have doubled in such a short period of time, so this outlier data point was removed from the analysis.

Physiological stress was not statistically associated with respondents’ assessment of goal progress by their response to the question: “Since our meeting, how would you assess your progress toward your financial goals?” A statistically significant association between lower physiological stress at the beginning of the meeting and the planner-imposed goal of improvement in credit score after three months was shown (t (12) = –9.81, p < .001). The average change in credit score was eight points, moving a mean of 717 to 725 over the course of three months.

Hypothesis 2 was partially supported in that goal progress was positively influenced by lower physiological stress, but only for the self-imposed goal (which was the focus of the meeting) and not the respondent-selected goal with this particular study design.

Study Limitations

Data constraints limit the generalizability of this study. The sample was restricted to 27 individuals, of which 16 answered the three-month follow-up survey asking about changes in credit score. Keeping attrition in mind, it is possible that only satisfied clients answered the follow-up surveys. The sample had a relatively high average credit score of 717 (SD = 55) when they first met with the financial counselor, limiting the generalizability of intentions to change and actual change to similarly positioned individuals. Given the high mean credit score, it is also plausible that the sample might not have felt as great of a need to change their financial situation as a sample of lower-credit individuals.

The use of bivariate analysis could also be seen as a limitation to this particular study, given that it measured the association between just two variables (stress and the level of TTM change within clients). As mentioned earlier, the sample size constrained this study to bivariate analysis, but future studies should consider multivariate analysis because there is potential for other factors to influence the change of a client’s TTM level.

Another important consideration is the fact that the skin temperatures of clients were measured only once—during the first (and only) meeting the clients had with a counselor, because this was the only way of measuring the level of physiological stress in our clients. Physiological stress changes rapidly and is based on immediate threats and opportunities. Future studies may want to consider long-term tracking of changes in physiological stress.

Discussion and Financial Planning Implications

Keeping data limitations in mind, this study provides evidence to suggest that physiological stress contributes to intentions to change and actual change.

Clients who experienced lower physiological stress at the initial meeting were associated with greater readiness to change their behavior and slight improvements in credit score three months later. The findings suggest that clients who were more relaxed during the initial meeting were able to hear the financial planner’s recommendations regarding small ways to improve one’s credit score and were more motivated to make improvements. The results of this study show support for Grable and Britt’s (2012) hypothesis that stress inhibits clients’ comprehension and implementation of financial planning recommendations. In other words, while some level of physiological stress may be necessary to motivate change, it is more advantageous for clients to be in a relaxed state of mind for financial planning.

In financial planning practice, it is helpful to note the temperature of clients’ hands when greeting them for their appointment—a cold hand may indicate a high physiological stress state, whereas a warm (not clammy) hand may indicate a more relaxed state. For those clients with cold hands, it may be beneficial to spend additional time joining with your clients before digging into the financial planning details of the meeting. Joining can help establish rapport with your clients and may help increase their trust in you as the financial planner.

One of the ways in which you can join with your clients is by using an active listening technique known as reflective listening. Reflective listening can help the financial planner better understand what clients are saying, even if the clients are not fully articulating what they are trying to say (Klontz, Horwitz, and Klontz 2015). When engaged in reflective listening it is important that questions not be asked as they can be seen as confrontational, potentially increasing client stress (Klontz, Kahler, and Klontz 2008; Miller and Rollnick 2002). Rather, the financial planner should say, “What I heard you say is … Is that correct?” and repeat back what the client said in your own words. It is important not to offer advice at this stage. This does two things. First, it confirms to the client that you listened to them. Second, it allows clients to confirm that you are on the same page. If done well, reflective listening can motivate clients to continue talking and developing possible solutions (Miller and Rollnick 2012).

Other techniques that can be used to help reduce stress stem from solution-focused financial therapy and motivational interviewing. When working with clients, particularly new clients, it is important to focus on the positive—what the client has been doing well—so that encouragement and support is offered up front, increasing the likelihood that clients continue the relationship and follow through on the strategies recommended during the meeting (Miller and Rollnick 2012). To do this, simply state what you observe the client to have done well before meeting with you.

Additionally, you can use scaling questions to have the client focus on a time where everything seemed to be going well for them. For example, you can use a series of scaling questions around a particular topic or goal the client has identified: “Thinking about [topic/event/goal], on a scale of 0 (low/terrible/not at all) to 10 (high/exceptional/goal is met), where do you currently see yourself on the scale? Where would you like to be on that scale? Now, think of what you are already doing that might be able to help you move up on this scale.”

Another way to help reduce stress and increase follow-through may be by offering homework to clients. At the end of the planning meeting, the planner should provide a summary to the client. Miller and Rollnick (2012) suggested that this helps show the client that they were indeed heard in the meeting and that the planner cares about the client. Additionally, a list of action steps or tasks for both the client and the planner to complete by agreed-upon dates should be given. Miller and Rollnick (2012) also showed that it is important that the planner have tasks, as this helps increase rapport with clients.

Some modest strategies can be done before a client even comes into the office. Rearranging the office environment is likely to result in positive outcomes. Creating a living room feel for the office helps keep clients’ physiological stress low even when they are presented with challenging questions (Herbers 2012; Britt and Grable 2012). Removing televisions playing financial news may also be effective at reducing client stress (Grable and Britt 2012).

For financial planners who want a tool to measure clients’ perceived stress, the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (Prawitz et al. 2006) may be useful. (The scale is free to use with permission; see pfeef.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Using-PFW-Scale-051606.pdf). It is a quick eight-item assessment based on a Likert-type scale with scores ranging from 1 to 10. Lower scores indicate reduced financial well-being/increased stress, whereas higher scores indicate a high level of financial well-being and little stress. The scale is a measure of perceived financial stress, versus objective physiological stress, although the scale may be helpful for financial planners who are not able to readily assess physiological conditions.

Understanding client stress may help financial planners better join with their clients to try to help reduce stress, and to know whether they should push clients forward given their stress level and current stage of change.

References

Britt, Sonya L., and John E. Grable. 2012. “Your Office May be a Stressor: Understand How the Physical Environment of Your Office Affects Financial Counseling Clients.” The Standard 30 (2) 5 and 13.

Causse, Mickael, Bruno Baracat, Josette Pastor, and Frederic Dehais. 2011. “Reward and Uncertainty Favor Risky Decision-Making in Pilots: Evidence from Cardiovascular and Oculometric Measurements.” Applied Psychophysiological Biofeedback 36: 231–242.

Grable, John E., and Sonya L. Britt. 2012. “Financial News and Client Stress: Understanding the Association from a Financial Planning Perspective.” Financial Planning Review 5 (3): 23–36.

Herbers, Angie. 2012. “Stress Fracture: How to Save Your Relationship with Your Client.” Investment Advisor, November: 1–5.

Horwitz, Edward J., and Bradley T. Klontz. 2013. “Understanding and Dealing with Client Resistance to Change.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (11): 27–31.

Kerkmann, Barbara C. 1998. “Motivation and Stages of Change in Financial Counseling: An Application of a Transtheoretical Model from Counseling Psychology.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (1): 13–20.

Klontz, Bradley, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz. 2008. Facilitating Financial Health: Tools for Financial Planners, Coaches, and Therapists. Erlanger, KY: The National Underwriter Company.

Klontz, Bradley T., Edward J. Horwitz, and Ted Klontz. 2015. “Stages of Change and Motivational Interviewing in Financial Therapy.” In B. T. Klontz, S. L. Britt, and K. L. Archuleta (Eds.), Financial Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 347–362). New York, N.Y.: Springer.

Lo, Andrew W., and Dmitry V. Repin. 2002. “The Psychophysiology of Real-Time Financial Risk Processing.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 14 (3): 323–339.

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 1992. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 2002. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change (2nd ed.). New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 2012. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed.). New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

Oei, Nicole Y. L., Walter T. A. M. Everaerd, Bernet M. Elzinga, Sonja van Well, and Bob Bermond. 2006. “Psychosocial Stress Impairs Working Memory at High Loads: An Association with Cortisol Levels and Memory Retrieval.” Stress: The International Journal on the Biology of Stress 9 (3): 133–141.

Pham, Michael Tuan. 2007. “Emotion and Rationality: A Critical Review and Interpretation of Empirical Evidence.” Review of General Psychology 11 (2): 155–178.

Prawitz, Aimee D., E. Thomas Garman, Benoit Sorhaindo, Barbara O’Neill, Jinhee Kim, and Patricia Drentea. 2006. “InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation.” Financial Counseling and Planning 17 (1): 34–50.

Prochaska, James O., and Carlo C. DiClemente. 1983. “Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51 (3): 390–395.

Prochaska, James O., Carlo C. DiClemente, and John C. Norcross. 1992. “In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Behaviors.” American Psychologist 47 (9): 1,102–1,114.

Prochaska, James O., John C. Norcross, and Carlo C. DiClemente. 1994. Changing for Good: A Revolutionary Six-Stage Program for Overcoming Bad Habits and Moving Your Life Positively Forward. New York, N.Y.: William Morrow and Company.

Vinkers, Christiaan, Renske Penning, Juliane Hellhammer, Joris C. Verster, John H. G. M. Klaessens, Berend Olivier, and Cor J. Kalkman. 2013. “The Effect of Stress on Core and Peripheral Body Temperature in Humans.” Stress: The International Journal on the Biology of Stress 16 (5): 520–530.

Wofford, J. C. 2001. “Cognitive-Affective Stress Response: Effects of Individual Stress Propensity on Physiological and Psychological Indicators of Strain.” Psychological Reports 88 (3): 768–784.

Xiao, Jing Jian, and Jiayun Wu. 2006. “Encouraging Behavior Change in Credit Counseling: An Application of the Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM).” Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=939434.

Zellars, Kelly L., James A. Meurs, Pamela L. Perrewe, Charles J. Kacmar, and Ana Maria Rossi. 2009. “Reacting to and Recovering from a Stressful Situation: The Negative Affectivity-Physiological Arousal Relationship.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 14 (1): 11–22

Citation

Britt, Sonya L., Derek R. Lawson, and Camila A. Haselwood. 2016. “A Descriptive Analysis of Physiological Stress and Readiness to Change.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (12): 45–51.