Journal of Financial Planning: August 2020

Executive Summary

- This study used data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances to investigate factors related to demand for financial planning services among both high-net-worth and non-high-net-worth women.

- This study found a positive relationship between women having a high net worth and using financial planning services. However, having a high net worth did not directly, but indirectly, affect demand for financial planning services, through such factors as race and inheritance expectancy.

- Personal characteristics, such as homeownership, education, and risk tolerance may play a key role in shaping female investors’ decisions regarding hiring financial planning professionals.

- Financial planning practitioners can use this research to determine: (1) to whom they should target their marketing efforts; (2) how to effectively reach this audience; and (3) how to help their clients to maximize their financial satisfaction over the long term.

Shan Lei, Ph.D., CFA, CFP®, is an assistant professor of finance in the College of Business at West Texas A&M University under the Texas A&M University system. Prior to that, she served as the director of the International Relations Department at Financial Planning Standards Board China.

Mark H. Kordes, CFP®, CLU®, ChFC®, CAP®, AEP®, has more than 30 years of experience in the financial services industry, having worked for HSBC, UBS, Merrill Lynch, and owning an independent RIA. Currently he is the CEO of his own consultancy firm.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

The number of affluent women is increasing both in the United States and globally, and women also now control over half of the personal assets in the U.S.1 and over 30 percent of private wealth in the world (Beardsley et al. 2016). Further, according to the “World Ultra Wealth Report” from Wealth-X,2 a provider of data and insight on the wealthy, the number of women with $30 million in assets worldwide increased 31 percent in 2018, compared to 2017. The report further pointed out that entrepreneurial activities contributed to this growth of wealthy women.

In addition to the growth in affluent women, it has been found that women are becoming more independent in their investment decision-making, relying on their own judgment rather than that of their spouses and families (Damisch, Kumar, Zakrzewski, and Zhiglinskaya 2010). Research by British bank Lloyds in 2012 suggested that the majority of women of all ages would play a dominant role in household financial decisions, from choosing the family’s bank to detailed future investment plans, by 2020.3 A more recent study found that women were involved in—or even took charge of—the household investment decision-making, especially among those women who own more assets and earn higher incomes (Kim, Gutter, and Spangler 2017).

Grasping the significance of these findings, we started to wonder about these women. Who are they? What characteristics do they have in common? Does their wealth influence their demand for financial planning services?

This paper attempts to shed light on the factors related to the demand for financial planning services among women. Most importantly, this study focuses on the role wealth plays in decisions made by women regarding using financial planning services.

Literature Review

Wealth and demand for financial services. Prior research has identified a positive relationship between investors’ wealth and demand for financial services. Consider the work of Hanna (2011), which was one of the earliest studies to use combined Survey of Consumer Finances datasets from 1998 to 2007 to examine the demand for financial planning services in helping with households’ investment and/or borrowing decisions. Results showed that household net worth was positively associated with the likelihood of using a financial planner.

Income level has also been used as an indicator of wealth in empirical studies. Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox (2002) found that income related positively to financial planning advice-seeking. Instead of using a static measure of financial resources, Cummings and James (2015) analyzed net worth and income, and suggested an increase of both correlated positively to seeking financial advice among the investors older than age 70.

Prior literature showed that the effect of wealth on demand for financial services depended upon the type of professionals and services investors seek. Using the 2012 National Financial Capability Study, Alyousif and Kalenkoski (2017) examined factors related to five types of financial advice: (1) debt counseling; (2) savings/investment; (3) mortgages/loans; (4) insurance; and (5) tax planning. Income was found to be positively related to demand for all five types of financial services, except for debt counseling.

Likewise, Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox (2002) found households with higher income and financial assets were less likely to seek financial planning for credit and borrowing decisions. However, in terms of saving/investment and comprehensive financial decisions, they indicated the likelihood of seeking financial planning services was positively associated with high income and financial assets.

Letkiewicz, Domian, Robinson, and Uborceva (2014) also demonstrated that investors with higher income and higher assets were more likely to seek financial planning services by examining a longitudinal dataset conducted by Financial Planning Standards Council (FPSC) in Canada.

Scott (2017) examined a proprietary dataset based on an online survey targeted at financial advice consumers in New Zealand. She found that income level was associated with the use of financial advisers. Higher-income investors were found to use professionals with the CFP® certification, who provide more comprehensive financial advice, while lower-income investors worked mostly with professionals with registered financial adviser, or RFA, status (an adviser classification, according to New Zealand law), who provides financial advice limited on less-complex products.

Homeownership. Homeownership was found to be positively related to demand for financial services (Collins 2010; Grable and Joo 2001), which might be due to other research findings that homeownership is an indicator of greater wealth (Beracha, Skiba, and Johnson 2017).

Grable and Joo (2001) examined the demand for professional financial services among faculty and staff from two large Midwestern universities and found that homeownership related positively to seeking broad professional financial advice.

Risk tolerance. Prior literature provides evidence that investors’ risk tolerance is closely associated with demand for financial services. According to Grable and Joo (2001), investors who demanded professional help tended to have higher risk tolerance. This finding was confirmed with subsequent research that investors with above-average risk tolerance had a higher probability to use financial planners, compared to their counterparts who were unwilling to take any financial risk (Hanna 2011; White 2016). It was noted that the above findings were based on the study on broad financial advice, which did not distinguish a specific type of financial advice.

Education and financial literacy. The probability of using financial advisers was found to increase with investors’ academic achievement (Hanna 2011; Seay, Kim, and Heckman 2016; White 2016). Consider the work of Seay, Kim, and Heckman (2016), who used the 2010 and 2012 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 to examine the impact of financial literacy on financial planner use in retirement planning. They noted that a higher level of financial literacy, such knowledge of diversification and mortgages, was associated with a higher likelihood of using financial planners.

Race. Demand for financial advice differed among races. For example, Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox (2002) analyzed the 1998 Survey of Consumer Finances data and found that Hispanic investors were less likely to seek professional advice for their investment decisions compared to their White counterparts. Collins (2010) examined the 2009 FINRA Financial Capability Survey and came to the same conclusion. White (2016) suggested that the common assets under management (AUM) fee structure may inadvertently be preventing Black and Hispanic households from using financial planners.

Conceptual Framework

According to Grable and Joo (2001), the process of seeking personal finance help consists of the following five steps: (1) the exhibition of a personal financial behavior(s); (2) the evaluation of the financial behavior(s); (3) the identification of financial behavior(al) causes; (4) a decision to seek help; and (5) a choice between help provider alternatives. This study focused on the fifth step of this process—a choice between help provider alternatives—to identify the factors related to choosing to use financial planners to help with investment decisions.

Researchers have recognized that wealth is a key determinant in the demand for financial planning. However, prior studies also found investors’ socioeconomics, demographics, expectations, and attitudes may also influence the demand for financial planning. This study proposed that these factors might serve as moderating factors in the relationship between wealth and demand for financial planning service.

Methodology

Data. This study used data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to analyze factors related to the demand for financial planning services among high-net-worth women in the United States.

The SCF is a national survey conducted every three years, managed by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in cooperation with the Statistics of Income Division of the Internal Revenue Service. It contains wide information on respondents’ income and wealth levels, use of financial planning services, and other financial and demographic information.

The survey sample size was 6,254. This study retained observations for female respondents with a final sample of 3,281.

Models. In all three models, the dependent variable was the use of financial planners when making investment or saving decisions (yes = 1, or no = 0). The SCF asks about the information sources used in investments. The question asks, “How do you (and your spouse/partner) make decisions about savings and investments? Do you call around, read newspapers, read material you get in the mail, use information from television, radio, an online service, or advertisements? Do you get advice from a friend, relative, lawyer, accountant, banker, broker, or financial planner? Or do you do something else?”

During the data collection, respondents were shown a list of options regarding which information source they chose when confronted with investment decisions. The main independent variable was whether the household’s net worth could be considered as high net worth. Though the segmentation criterion varies, it has been widely accepted that a $1 million net worth can be considered “high net worth” (Frank 2008; Zakrzewski et al. 2019).

Household income and homeownership were included (Cummings and James 2015; Letkiewicz, Domian, Robinson, and Uborceva 2014) to account for the respondents’ economic situation. A set of individual demographics was included to control for age, marital status, education, race, employment status, and family size (Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox 2002; Seay, Kim, and Heckman 2016). This study also controlled for each respondent’s risk tolerance (Grable and Joo 2001; White 2016), inheritance expectancy, and investment horizon (Cummings and James 2015; Lei 2019).

To isolate the effect of having high net worth on the use of financial planners, a decomposing method was adopted. Early users of this method were Jackson and Lindley (1989) who used the same method to examine the wage gap between men and women, followed by many other researchers, including Fisher and Yao (2017); Fontes and Kelly (2013); and Yao and Lei (2018). First, the “use of financial planners” was regressed on control variables in a reduced model. Then, “having a high net worth” was added as an independent variable into an intermediate model. Finally, all interaction terms between “having a high net worth” variable and the control variables were added in the full model.

A likelihood ratio test, which compared the full interaction model and the reduced model, was used to determine if having a high net worth contributed to the differences in demand for financial planning services. This difference can then be decomposed into the constant effect and the coefficient effect. A significant constant effect will be confirmed if the estimated coefficient of the “having a high net worth” variable in the full interaction model is significant. This indicates that the difference in the demand for financial planning services would be due only to the difference in having a high net worth. By comparing the full interaction model and the intermediate model, a significant likelihood ratio would indicate the existence of the coefficient effect, which indicates a high net worth difference in demand for financial planning services beyond the factors controlled in the model.

Results

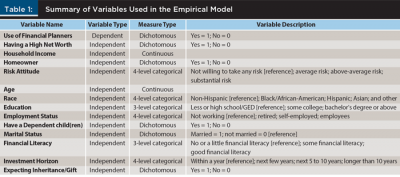

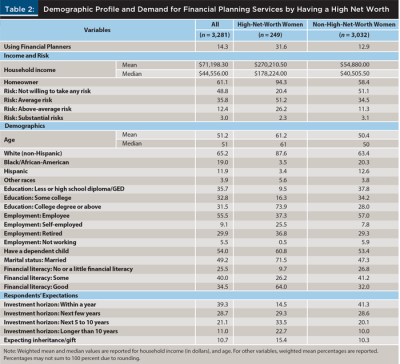

Descriptive statistics. Table 1 shows the coding of each variable used in this study. Table 2 presents the resulting descriptive statistics for each variable. In the total sample, nearly 8 percent of women can be considered high-net-worth individuals. Fourteen percent of women investors reported using financial planners when confronting investment or saving decisions. The percentage of using financial planners among the high-net-worth women investors (32 percent) was almost three times as high as non-high-net-worth women investors (13 percent).

The mean household income for the total sample was $71,198, and median household income was $44,556. The mean household income was $270,210, and median household income was $178,224 for the high-net-worth women investors. The mean and median household income for non-high-net-worth women investors was $54,880 and $40,505 respectively. On average, a majority of high-net-worth women investors are homeowners (94 percent).

Though in general, very few women investors were willing to take substantial financial risk when making investment decisions, more women investors with high net worth were willing to take above-average (26 percent) or average financial risk (51 percent), than non-high-net-worth women investors (11 percent and 35 percent respectively). More than half of the women investors not classified as high net worth were not willing to take any risk when making investment decisions, whereas this proportion was only 20 percent among the high-net-worth women investors.

A large proportion (74 percent) of the high-net-worth women investors had a college degree or above, while only 28 percent of the non-high-net-worth women investors did. Sixty-four percent of the high-net-worth women investors were financially literate. For non-high-net-worth women investors, over half of them worked for others and nearly 8 percent were self-employed. By contrast, over one-fourth of high-net-worth women investors were self-employed.

On average, high-net-worth women investors were older (average age of 61) than their counterparts (average age of 50). A majority of the high-net-worth women investors were White (88 percent), and 20 percent and 13 percent of the non-high-net-worth women investors were Black and Hispanic, respectively. Twenty-three percent of the high-net-worth women investors reported having longer than a 10-year investment horizon, while 41 percent of the non-high-net-worth women investors claimed having an investment horizon within a year.

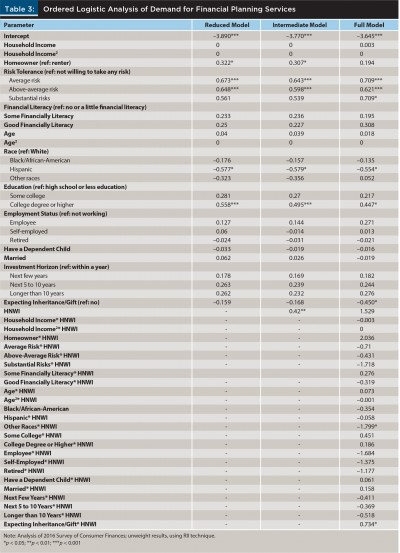

Multivariate analysis. In the intermediate model, after controlling for other variables, the high-net-worth indicator variable was significantly related to use of financial planners (see Table 2). Compared with non-high-net-worth women investors, high-net-worth women investors were 52 percent more likely (estimated coefficient t = 0.42) to use financial planners. The likelihood ratio test of “having a high net worth” indicator variable and the set of interaction terms showed a statistically significant result (p < 0.001).

As shared in the Model section, this result suggests that demand for financial planning services differed in high-net-worth women and non-high-net-worth women. Therefore, further analysis was conducted to decompose this total between-group difference in demand for financial planning services. The decomposition showed an insignificant constant effect and a significant coefficient effect (p < 0.001), indicating that having a high net worth affected demand for financial planning service through the control variables, rather than through having a high net worth itself.

As shown in the full interaction model (Table 3), race and expecting an inheritance/gift affected the demand for financial planning services. Among the high-net-worth women investors, those from races other than White (including Asians) were 83 percent less likely to seek financial planning service compared to their White counterparts (estimated coefficient = –1.799 for the interaction effect of race and having high-net-worth variables). Compared to non-high-net-worth women investors with no inheritance expectancy, non-high-net-worth women investors who expected an inheritance or gift were 36 percent less likely to seek a financial planning service (estimated coefficient = –0.45 for the main effect of inheritance/gift expectancy). However, for high-net-worth women investors, those with inheritance expectancy were 1.1 times more likely to seek financial planning service (estimated coefficient = 0.734 for the interaction effect of the inheritance/gift expectancy and having high net worth).

Implications for Financial Planners

This study adds to the existing literature by showing factors related to the demand for financial planning services among women investors. The study identified the positive role that having a high net worth has in the demand for financial planning services. When these factors are viewed in the aggregate, a profile of the women who are more likely to use financial planning services emerges. They share some similar characteristics: wealthy, well-educated, financially literate, and have a relatively longer investment horizon (as shown in Table 1). Compared to their non-high-net-worth counterparts, high-net-worth women investors showed willingness to take average or above-average financial risks when making investment decisions. High-net-worth women investors also expected to receive an inheritance or gift.

However, knowing which women to market to and determining the size of the market is not enough for commercial success. As a result, financial planners need to know the right message to communicate to these women, the right time to communicate, and the right media. The goal is to ensure that the message resonates with them by being relevant with respect to their values and beliefs.

For example, if we know that they are likely to be married with children, we may want to start by appealing to their sense of family, rather than the benefits of one investment over another. In the quest to find these answers, a traditional research approach can be employed. A faster and more effective “test-and-learn” technique can be used. Test for such things as: What topics attract their attention? What creates a positive impression (and negative)? What causes them to take action? What causes them not to take action? Discounts? Having complete information?

Once the financial planner knows to whom and how they wish to communicate, the question becomes, how can planners help these women maximize their satisfaction over the longer term? To answer this, a better understanding of relevant behavioral economics factors, such as cognitive bias, emotions, and social influences, is warranted. This could be evaluated by future research.

In addition to the behavioral aspects, financial planners would be well served to carefully detail and understand the client journey and the client’s experience of the journey, then make adjustments to improve the experience. Financial planners, and financial services institutions, are likely to realize benefits if they use these findings to enhance their business models to better serve women who have a propensity for financial planning services.

This study further revealed that having a high net worth did not directly affect demand for financial planning service, but factors like race and expected inheritance indirectly did. Wealth levels help identify unique client groups for wealth management companies, including high-net-worth and non-high-net-worth clients. However, it is reported that the latter has not been well served due to having less financial literacy.

This study showed that financial planners should get to know their clients beyond the wealth itself. For example, the findings of this study echoed previous research that inheritance is still the major way women get rich.4 For non-high-net-worth women in this study, expecting an inheritance reduced their probability to use financial planning service. By contrast, for high-net-worth women, expecting an inheritance increased their probability of using a financial planning service.

These findings indicated that financial planners might consider different marketing strategies to serve non-high-net-worth and high-net-worth women. For non-high-net-worth women, identify why they are unwilling to work with a financial planner if they were to get an inheritance. Is it because they need to use the inheritance to pay for the debts? To consume luxury goods? Education is needed for this group of investors to understand the importance of a disciplined investment and debt management strategy.

Further, this study showed that demand for financial planning services was associated with a number of household characteristics. For example, risk tolerance was found to be an important factor. Compared to women investors who are not willing to take any risks when making financial decisions, those who are willing to take average or above-average risk showed a higher probability to seek help from financial planners about their investment decisions.

Homeowners were found to be more likely to seek advice from financial planners, which was consistent with prior research (Grable and Joo 2001). Also like prior research (Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox 2002; Seay, Kim, and Heckman 2016), this paper found a positive relationship between education and demand for financial planning services, showing that women investors with higher levels of education were found to be more likely to use financial planners.

This study identified factors related to why women investors decide to use financial planners and the role having high net worth plays. Considering an increasing number of unsatisfactory financial services received among high-net-worth women investors, a direction for further research could be to examine the characteristics of this niche group and how they relate to financial decision-making. It is important for financial professionals to create programs or procedures to provide women with better service and help them increase their financial wellness.

Endnotes

- See “A Record Number of Women Are Now Among the World’s Richest People,” by Natasha Bach, posted March 6, 2018 by Fortune. Available at fortune.com/2018/03/06/record-number-female-billionaires-rich-women.

- See “Ultra Wealthy Analysis: The World Ultra Wealth Report 2018,” at wealthx.com/report/world-ultra-wealth-report-2018.

- See “Women Now in Charge of Major Financial Decisions,” by Sam Marsden, posted Sept. 28, 2012 by The Telegraph. Available at telegraph.co.uk/finance/personalfinance/savings/9571809/Women-now-in-charge-of-major-financial-decisions.html.

- See endnote No. 1

References

Alyousif, Maher, and Charlene M. Kalenkoski. 2017. “Who Seeks Financial Advice?” Financial Services Review 26 (4): 405–432.

Beardsley, Brent, Bruce Holley, Mariam Jaafar, Daniel Kessler, Federico Muxí, Matthias Naumann, Tjun Tang, André Xavier, and Anna Zakrzewski. 2016. “New Strategies for Nontraditional Client Segments.” Boston Consulting Group. Available at bcg.com/publications/2016/financial-institutions-asset-wealth-management-new-strategies-for-nontraditional-client-segments.aspx.

Beracha, Eli, Alexandre Skiba, and Ken H. Johnson. 2017. “Housing Ownership Decision Making in the Framework of Household Portfolio Choice.” Journal of Real Estate Research 39 (2): 263–287.

Collins, J. Michael. 2010. “A Review of Financial Advice Models and the Take-Up of Financial Advice.” University of Wisconsin’s Center for Financial Security whitepaper, available at cfs.wisc.edu/2010/09/23/a-review-of-financial-advice-models-and-the-take-up-of-financial-advice.

Cummings, Benjamin F., and Russell N. James. 2015. “Determinants of Seeking Financial Advice among Older Adults.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 26 (4): 129–147.

Damisch, Peter, Monish Kumar, Anna Zakrzewski, and Natalia Zhiglinskaya. 2010. “Leveling the Playing Field: Upgrading the Wealth Management Experience for Women.” Boston Consulting Group report, available at bcg.com/documents/file56704.pdf.

Elmerick, Stephanie A., Catherine P. Montalto, and Jonathan J. Fox. 2002. “Use of Financial Planners by U.S. Households.” Financial Services Review 11 (3): 217–231.

Fisher, Patti J., and Rui Yao. 2017. “Gender Differences in Financial Risk Tolerance.” Journal of Economic Psychology 61: 191–202.

Fontes, Angela, and Nicole Kelly. 2013. “Factors Affecting Wealth Accumulation in Hispanic Households: A Comparative Analysis of Stock and Home Asset Utilization.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35 (4): 565–587.

Frank, Robert. 2008. Richistan: A Journey Through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich. New York, N.Y.: Crown Publishing Group.

Grable, John E., and So-hyun Joo. 2001. “A Further Examination of Financial Help-Seeking Behavior.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 12 (1): 55–74.

Hanna, Sherman D. 2011. “The Demand for Financial Planning Services.” Journal of Personal Finance 10 (1): 36–62.

Jackson, John D., and James T. Lindley. 1989. “Measuring the Extent of Wage Discrimination: A Statistical Test and a Caveat.” Applied Economics 21 (4): 515–540.

Kim, Jinhee, Michael S. Gutter, and Taylor Spangler. 2017. “Review of Family Financial Decision Making: Suggestions for Future Research and Implications for Financial Education.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (2): 253–267.

Lei, Shan. 2019. “Single Women and Stock Investment in Individual Retirement Accounts.” Journal of Women & Aging 31 (4): 304–318.

Letkiewicz, Jodi C., Dale L. Domian, Chris Robinson, and Natallia Uborceva. 2014. “Self-Efficacy, Financial Stress, and the Decision to Seek Professional Financial Planning Help.” Academy of Financial Services presentation, October 2014 AFS Annual Meeting. Available at academyfinancial.org/resources/Documents/Proceedings/2014/E7_Letkiewicz_Domian_Robinson_Uborceva.pdf.

Scott, Janine K. 2017. “Consumers of Financial Advice in New Zealand.” Financial Planning Research Journal 3 (2): 68–86.

Seay, Martin, Kyoung Tae Kim, and Stuart Heckman. 2016. “Exploring the Demand for Retirement Planning Advice: The Role of Financial Literacy.” Financial Services Review 25 (4): 331–350.

White Jr., Kenneth J. 2016. “Financial Planner Use Among Black and Hispanic Households.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (9): 42–51.

Yao, Rui, and Shan Lei. 2018. “Source of Information and Projected Household Investment Portfolio Performance.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 46 (3): 219–237.

Zakrzewski, Anna, Tjun Tang, Galina Appell,

Renaud Fages, Andrew Hardie, Nicole Hildebrandt, Michael Kahlch, Martin Mende, Federico Muxí, and André Xavier. 2019. “Global Wealth 2019: Reigniting Radical Growth.” Boston Consulting Group white paper, available at image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Reigniting-Radical-Growth-June-2019_tcm9-222638.pdf.

Citation

Lei, Shan, and Mark Kordes. 2020. “Women, Wealth, and Demand for Financial Planning Services.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (8): 48–55.