Journal of Financial Planning: August 2017

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is the head of financial and fiduciary education for Horace Mann, the largest multi-line insurance and financial services company focused on educators’ needs.

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a state bar certified specialist in estate planning, trust, and probate law and the founder of Estate Plan, Inc.

Qualified charitable distributions (QCDs) from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) to qualified charities were first allowed in 2006, but it was a bi-annual planning question whether Congress would allow the transaction for another two years. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (PATH Act) eliminated these concerns by permanently adding QCDs to the law starting in 2016.

With a QCD, up to $100,000 of an IRA’s potentially taxable income may be contributed to a qualifying charity by an individual who has reached age 70½. The QCD is not reported in income, and no charitable deduction is claimed. Although it seems like the result would be the same if the individual included the IRA distribution in income, contributed the distribution to charity, and then deducted the charitable contribution on his or her tax return, using a QCD is more beneficial in many scenarios. Here are some examples:

Financial institutions are not obligated to withhold income taxes from a QCD, saving the client who wants to contribute the entire distribution, often a mandatory required minimum distribution (RMD), the inconvenience of having to sell investments, further increasing taxable income, to make up for the withholding.

Individuals who claim the standard deduction can benefit from the full charitable deduction even though they do not itemize.

The full amount of a QCD can be excluded from income even when the charitable contribution exceeds the 50 percent/30 percent adjusted gross income (AGI) limitation on charitable contributions.

Because QCDs are a per-individual benefit, if spouses filing jointly both meet the eligibility rules, up to $200,000 can be excluded from their income.

Distributions from IRAs eliminate income in respect of decedent and the potential for double taxation on the owner’s estate tax return and beneficiaries’ income tax returns.

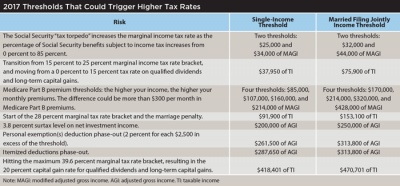

However, the main reason QCDs are better is they avoid raising income above thresholds that could trigger higher marginal tax rates, the taxability of Social Security benefits, the means test on monthly Medicare Part B premiums, the 3.8 percent surtax on investment income, and AGI limitations on deductions, such as medical expenses (a 10 percent threshold), miscellaneous itemized deductions (a 2 percent threshold), and the phase-out of itemized deductions and personal exemptions at higher income levels.

These thresholds for 2017 are displayed below:

Examples

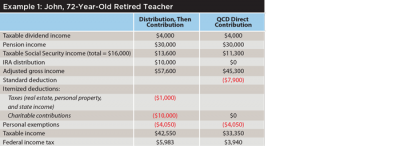

Example 1: John, age 72, is a single, retired school teacher. He would like to contribute his $10,000 RMD to charity to fulfill a charitable pledge he made earlier in the year. A comparison of the tax consequences is shown in the table below:

For John, the difference is $2,043 ($5,983 – $3,940) in federal income tax liability by making a QCD rather than taking the distribution and then making a contribution. The difference occurred because fewer of the dividends were subject to income tax because the IRA distribution raised the marginal tax rate to 25 percent on part of the income, $2,300 less of Social Security payments was subject to tax, and the charitable contribution only provided $3,100 of additional tax benefit over the standard deduction.

Example 2: Jack and Jill, both 84 years old, are married, retired business owners. Jill would like to use her IRA RMD as the source of a $100,000 contribution to her favorite charity. In addition to helping the charity, it will reduce the couple’s taxable estate. The Example 2 table shows a comparison of the income tax consequences.

For Jack and Jill, the difference is $1,190 ($39,767 – $38,577) in federal income tax by making a QCD rather than taking the distribution and then making a contribution. The difference occurred because $728 of 3.8 percent investment surtax was avoided, as was the phase-out of itemized deductions and personal exemptions. In addition, Jack and Jill, by not crossing the $320,000 threshold, avoided a hike in their Medicare Part B premium from $267.90 to $348.30 per month (a savings of $80.40 per month or $964.80 for the year). Therefore, total savings for the year by using a QCD was $2,154.80 ($1,190 + 964.80).

Qualifications and Rules

To qualify as a QCD, the distributions must be made to an organization that qualifies for a charitable deduction other than a private (grant-making) foundation, donor-advised fund, or charitable trust. IRAs that may make QCDs include any IRA or individual retirement annuity, including a Roth IRA and inherited IRA, but not a simplified employee pension or a SIMPLE retirement account that is still being funded by an employer.

In accounting for QCDs, all IRAs are aggregated. For example, assume your IRA 1 is worth $50,000 of which $40,000 would be taxable income if distributed in a taxable distribution. IRA 2 is worth $500,000 and holds undistributed taxable income of $400,000. A QCD of $50,000 may be made from IRA 1 because there is enough pre-tax income in both IRAs to cover the full $50,000 amount. After the contribution is made, IRA 1 is closed.

As a result of the QCD, all $40,000 of IRA 1’s taxable income is treated as a QCD. The remaining $10,000 of the $50,000 QCD is deemed to have come from IRA 2. IRA 2 is still worth $500,000, but the undistributed taxable income is now $390,000 ($400,000 – $10,000).

QCDs are not normally made from Roth IRAs because they are nontaxable. However, if a Roth IRA has potentially taxable income because of a Roth IRA conversion and the Roth IRA conversion is less than five years old, then a QCD from a Roth IRA might be beneficial.

QCDs may be made by making a direct transfer from the IRA to the qualifying charity; or the IRA may mail a check made payable to the qualifying charity directly to the IRA owner who then delivers the check to the charity. Be careful using this latter approach. If the check is written to the IRA owner who then writes a check to the charity, the transfer does not qualify as a QCD.

As you advise clients over age 70½ about their charitable giving options, keep QCDs in mind— they are convenient and offer the opportunity to engage in tax planning.