Journal of Financial Planning: August 2015

Melissa J. Wilmarth, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the department of consumer sciences at the University of Alabama. Her research interests include family and consumer economics, economic well-being of families, economic hardship, and stress and relationship outcomes.

Martin C. Seay, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor at Kansas State University. His career objective is to provide impactful consumer finance research while educating ethical, thoughtful, and well-rounded financial planners. His research focuses on consumer borrowing decisions and how psychological characteristics inform financial behavior.

Sonya L. Britt, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor at Kansas State University. Her research interests include money issues within marriage, predictors of money arguments and their influence on relationship satisfaction and divorce, financial literacy effectiveness, and the influence of physiological stress in the financial planning and counseling setting.

Executive Summary

- This research investigated the association and influence of income contribution, self-esteem, perceived control, and marital arguments on marital happiness among married women.

- Analysis of a sample of 1,395 married women ages 43 to 53 revealed a negative association between a woman’s relative income contribution and her reported happiness levels.

- The interplay of results related to arguments about money, chores, and income contribution highlight the potential effects of shifting gender roles due to increased female employment.

- Findings suggest that being aware of financial and psychological factors that influence the client is important in retaining married clients.

From a financial planning perspective, there are significant incentives to help facilitate healthy marriages, as marital discord and divorce severely affect a financial planning professional’s ability to serve his or her clients effectively. Financial issues may be masked when a financial planner works with a married couple. Planner recommendations may not be effective if discord and conflict are present and not addressed or accounted for when working with couples.

Financial stress and disagreements have been identified as a leading source of marital conflict. Financial stress is one of the most frequently cited problems for married couples (Oggins 2003; Stanley, Markman, and Whitton 2002). Divorce, and the splitting of financial resources between two newly formed households, has severe implications for financial well-being, providing financial planners the incentive to support healthy marriages whenever possible.

George Kinder (2014) is known for his life planning model. His approach encourages planners to engage all aspects of a client’s aspirations in order to win a client’s trust and continued engagement. A large component of a married individual’s life is his or her marriage. This highlights the importance of considering the influence of a client’s marriage when working to complete a long-term financial plan. Although financial planners should not act as marriage and family therapists, planners can consider how contribution of income within a marriage and psychological characteristics influence their clients’ lives.

Significant financial benefits are associated with marriage, including higher lifetime net worth accumulation compared to non-married individuals (Lupton and Smith 2003; Vespa and Painter 2011). Vespa and Painter also found that couples who marry their only cohabiting partner experience the highest lifetime net worth of any other marital status. Developing an understanding of the factors that contribute to marital happiness is important to allow financial planners to better identify relationship stressors.

This paper investigates how three factors are related to happiness: (1) psychological well-being; (2) household income contribution; and (3) the presence of marital arguments. These factors are known to be related to a wife’s marital happiness as reported by women.

By expanding the financial planning community’s understanding of the factors that contribute to marital happiness, this research aims to help financial planning professionals be better prepared to identify stressors and barriers within a marital relationship that may impact the success associated with planning implementation. With this insight, financial planning professionals can either directly provide guidance to help couples, or better identify when a specific referral to appropriate professionals is needed.

Conceptual Framework

Becker (1976) provided insight into how individuals make economic decisions, indicating that individuals seek to invest in and allocate their resources to maximize happiness—including marital happiness—over the course of their lives. Those who have not allocated financial resources appropriately tend to experience negative marital happiness effects. Couples experiencing financial instability, low levels of income, and economic problems consistently report lower levels of marital happiness (Amato, Booth, Johnson, and Rogers 2007; Cutrona, Russell, Abraham, Gardner, Melby, Bryant, and Conger 2003; Dakin and Wampler 2008; Rauer, Karney, Garvan, and Hou 2008). Similarly, couples living with a higher socioeconomic status not only have a reduced risk of separation and divorce, but also report higher levels of marital happiness (Karney and Bradbury 1995).

Previous research has documented that, in addition to overall income levels, relative income levels between spouses may influence marital happiness. Finances play a pervasive and influential role in relationships due to their strong link with issues of power, control, and decision making (Stanley et al. 2002). In the last 30 years, the number of dual income households has continually increased (Raley, Mattingly, and Bianchi 2006). We have also experienced increased labor force attachment and earning power for women (Blau and Kahn 2007), and wealth accumulation that is greater for those who are married (Lupton and Smith 2003). These economic changes have challenged traditional gender roles in marriage; the consequences of the effect have been felt on marital happiness.

Although previous research has largely identified a positive relationship between income level and happiness within a marriage, it appears to be a nuanced relationship. More recent research suggests that the source of the income and relative contributions of income may be influential on marital happiness. In fact, marital happiness may actually decline when a wife earns more than her husband.

Changes in relative income may lead to marital dissatisfaction; specifically, when a wife’s income increases relative to her husband’s income, marital satisfaction tends to decrease (Furdyna, Tucker, and James 2008). This change in relative income is even positively associated with the risk of divorce (Kalmijn, Loeve, and Manting 2007; Rogers and DeBoer 2001).

As a wife’s income and her contribution to the family income increases, both relatively and actually, development of a sense of unfairness over the division of labor in the household and challenges to the head of household status can arise (Rogers 2004). Conversely, it is important to note that an increase in overall income level may make the marriage more attractive for the spouses. This can lead to an increase in marital happiness and reduce the risk for marital dissolution (Oppenheimer 1997; Sayer and Bianchi 2000).

Becker (1976) also suggested that psychological and relational barriers may impact an individual’s level of utility. Two psychological factors in particular have been found to influence an individual’s marital happiness: perceived control and self-esteem. As related to perceived control, Solaimani (2014) found that couples with an external locus of control report lower levels of marital satisfaction, while those with high marital satisfaction have more internal locus of control. Similarly, individuals with high perceived mastery (a type of internal locus of control) report the highest marital satisfaction and the lowest marital conflict (Myers and Booth 1999). Having a low sense of perceived mastery (more external locus of control) is associated with negative conflict resolution, low commitment to mutual relations, lower marital satisfaction, and higher aggression (Myers and Booth 1999).

Past research has also identified a positive correlation between self-esteem and relationship satisfaction (Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, and Kusche 2002; Shackelford 2001), possibly due to the behaviors commonly associated with high self-esteemed individuals. For example, those who exhibit high self-esteem may be more likely to show more relationship-enhancing behaviors, whereas individuals with low self-esteem may engage in more relationship-damaging behaviors (Murray et al. 2002). The investigation of the psychological factors, like mastery and self-esteem, are important when studying the influence of relative income on marital happiness. As Becker (1976) suggested, these factors may increase utility, and in a place where marital happiness may be threatened by changes in relative income, these factors may protect martial happiness.

Relational barriers, such as arguments, have also been found to be a contributor to marital unhappiness. In particular, money arguments are known to be predictive of divorce (Britt and Huston 2012; Dew, Britt, and Huston 2012). According to Britt and Huston, arguments about money are the top contributor to relationship dissatisfaction and among the top contributors to divorce. This holds true worldwide, as international samples have reported that frequent intense quarrels are significantly associated with negative marital outcomes and divorce (Xu, Zhang, and Amato 2011).

The negativity associated with arguments is the key determinant in what impact the arguments have on the relationship. Nevertheless, some evidence suggests that occasional arguments are not necessarily bad. Instead, arguments may represent a form a communication and have no negative effect on a relationship (Stanley et al. 2002). Within the framework presented here, arguments could influence marital happiness as the frequency of arguments may change as a couple experiences changes in their relative income.

Based on this conceptual framework (Becker 1976), the purpose of this study was to investigate the association and influence of income contribution, self-esteem, perceived control, and marital arguments on marital happiness among married women.

We hypothesized that as a wife earns more income and her income contribution becomes more than her husband’s, she may experience declines in marital happiness. Second, we hypothesized that women with higher self-esteem and higher mastery/internal control would have higher marital happiness. Finally, women who reported more marital arguments, specifically about money, were hypothesized to have lower marital happiness.

Research Methods

Data for this study were taken from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 cohort (NLSY79). The NLSY79 is a nationally representative longitudinal survey that contains information from annual surveys from 1979 through 1994 and information from biennial surveys since. This study used data collected from the 2010 administration of the survey, unless otherwise noted. Given the research question, the sample for this analysis was limited to women who reported being currently married and those who completed the series of questions related to spousal arguments. Consequently, a total of 1,395 married women respondents were included in the sample for this study.

The dependent variable for this study was based on a question from the 2010 survey that asked women to rate their marital happiness. Potential responses included very happy, fairly happy, and not happy at all. Of the 1,395 respondents, 917 respondents reported being very happy; 424 reported being fairly happy; and only 54 respondents reported being not happy at all. Ideally, information would be retained about those who were not happy to allow for a more in-depth analysis, but this was not possible given the small number of respondents in the “not happy at all” subgroup. Consequently, a dichotomous measure of marital happiness was generated, with respondents coded as either as very happy (= 1) or not (= 0) with their marriage (this category was created by collapsing response categories other than “very happy” into one group).

A number of socioeconomic control variables were included in the analysis. These control variables included age, number of marriages, current marital duration, education, race/ethnicity, and number of children. Three different variables were used to proxy a respondent’s financial situation: family income, family net worth, and the percent of family income contributed by the respondent. To meet model assumptions, and for ease of interpretation, family income and family net worth were transformed using a log base 10 estimate.

Each respondent’s self-esteem was measured using Rosenberg’s 10-item self-esteem scale (Rosenberg 1965). Self-esteem was most recently assessed in the 2006 administration of the NLSY79. Self-esteem tends to remain relatively unchanged during adulthood, particularly for women between the ages of 25 and 50 (Robins and Trzesniewski 2005), so the older data collection should not pose a serious concern in the context of the study results. Responses were collected on a four-item Likert type scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, with strongly agree being scored as a 0, and strongly disagree scored as a 3. The reliability of the self-esteem scale was acceptable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88.

The NLSY79 employs the seven-item Pearlin Mastery Scale (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, and Mullen 1981) to measure an individual’s feeling of personal mastery. Mastery was most recently assessed in the 1992 administration of the NLSY79. Personal mastery is a reflection of an individual’s self-concept, which is the extent to which an individual perceives himself or herself to be in control of forces that impact their life. Nearly all mastery validity studies have concluded that perceived control is relatively stable throughout adulthood (see Grob, Little, and Wanner 1993). Responses were collected on a four-item Likert type scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The reliability of the scale was acceptable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .80. In accordance with previous research, a respondent was identified to have high personal mastery if their overall score was 23 or higher (Nyqvist, Forsman, and Cattan 2013).

The NLSY79 contains a comprehensive set of questions designed to identify the frequency upon which spouses argue about various topics. Specifically, questions were asked to assess the frequency with which spouses argue about chores, children, money, affection, religion, time use, drinking, other women, in-laws, and other relatives. These questions were asked of the wife and responses were measured as often, sometimes, hardly ever, and never. For ease of interpretation, responses were coded so that higher scores correspond with more frequent arguments.

Results

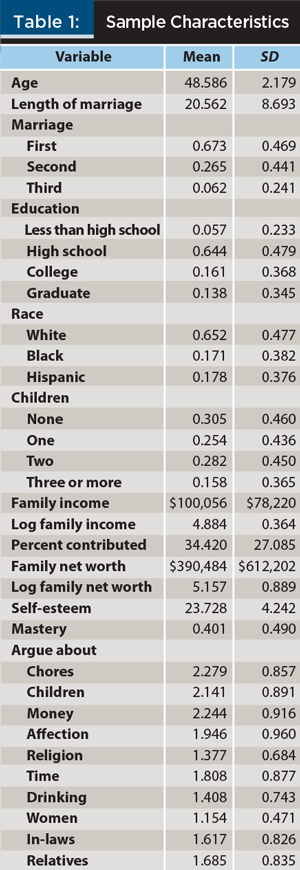

A description of the sample characteristics are found in Table 1. Because of the longitudinal nature of the dataset and the cohort, the age range of respondents in 2010 was between 45 and 53. Most marriages were of significant length (20.56 years), with only 10.50 percent of respondents indicating their marriage was less than seven years old. The majority of respondents’ highest level of education was a high school diploma (64.44 percent). The majority indicated that they were white (65.20 percent). Not surprisingly, given the age range of the sample, 69.40 percent of respondents indicated having children, with 15.80 percent reporting having three or more children. The sample’s mean and median family income were $100,056 and $84,242, respectively. Similarly, the sample’s mean and median family net worth were $390,484 and $204,000, respectively. Overall, this indicates that the sample consisted of higher family income and family net worth individuals, compared to national averages. The average woman contributed 34.42 percent of family income, with cases ranging from contributing none to all of the income.

With a range of 8 to 30 on Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale, the average reported self-esteem score was relatively high at 23.72 (SD = 4.24). Based on the Pearlin Mastery Scale, 40.1 percent of respondents had high personal mastery. Variation was evident in all argument categories; however, on average, respondents had low overall levels of arguments. One a scale of 1 to 4, only arguments about chores (2.28), children (2.14), and money (2.24) had average scores greater than 2, indicating the presence of some consistent arguments on the subject.

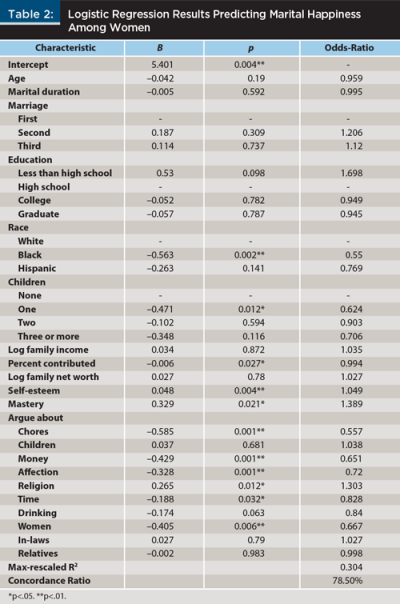

As shown in Table 2, family income (as well as family net worth) was not associated with martial happiness after controlling for other factors. However, as was hypothesized, a wife’s relative contribution to family income was found to be significant. This result was perhaps due to challenges to power and resource contribution norms. Specifically, as a wife’s contribution to overall family income increased, the odds of her reporting high levels of marital happiness decreased.

We hypothesized that psychological and relational barriers were preventing resources from being used to produce marital happiness. Evidence was found to support this possibility, as results from the logistic regression model showed that increases in self-esteem were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting high levels of marital happiness. A one-unit increase in a woman’s self-esteem score was associated with a 4.9 percent increase in the odds of reporting very high levels of marital happiness, holding all else equal. This finding supports past research that identified a positive correlation between self-esteem and relationship satisfaction (Murray et al. 2002; Shackelford 2001).

Results also indicated that high levels of perceived control were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a high level of marital happiness. Consistent with past literature (see Myers and Booth 1999 and Solaimani 2014), those with a greater perception of control over the forces that impact their life were more likely to experience higher marital happiness than those that perceived a lack of control of the forces impacting their life. Having a more external perception of locus of control has been identified as being associated with negative conflict resolution, low commitment to mutual relations, and higher aggression. According to Myers and Booth, these are behaviors that can serve to lower marital happiness.

As expected, the regression results revealed a strong generally negative association between spousal arguments and marital happiness. Past research has specifically identified money arguments to be a top predictor of divorce (Britt and Huston 2012; Dew, Britt, and Huston 2012). It is important to note that in addition to money arguments, spousal arguments about chores, affection, time use, and other women were all found to be associated with a decreased likelihood of reporting high marital happiness. Conversely, spousal arguments about religion were associated with high marital happiness. This serves to suggest, in line with Stanley et al. (2002), that not all arguments are necessarily detrimental. If the arguments are not negative, they may serve as an open form of communication in the marriage.

Data Limitations

Some limitations from the current study should be noted. First, NLSY data only permitted the investigation from a woman’s perspective; no insight could be gained into income contribution and how psychological constructs inform men’s happiness levels. Although the investigation of women is interesting and influential given the increasing income equality of men and women, being able to investigate men will provide a fuller picture of the relationship. As a result, future studies would benefit from an understanding of men’s marital happiness. In addition, due to the longitudinal nature of the NLSY, respondents were between the ages of 45 and 53 during the time period of analysis. Samples with different age groups or larger age ranges may have different results.

Additionally, data limitations required both the self-esteem and mastery variables to be constructed using information collected in previous years. It is unlikely that respondents’ personality characteristics changed dramatically (Grob et al. 1993; Robins and Trzesniewski 2005), yet more recent assessments of those variables could possibly result in different findings.

The sample consisted of individuals who were highly satisfied with their marriages—more than two-thirds of the sample reported being very happy with their current marriage. Many couples who were unsatisfied with their marriage likely divorced prior to the administration of this survey, providing a potentially biased sample. The average marital duration of individuals in the sample was 21 years. Generalization of this study’s results is restricted to clients of similar demographic and marital history characteristics.

Finally, there is a limitation in the measurement of the argument variables. Respondents were asked to assess the frequency of arguments with their spouse around the listed topics. The measure did not address the intensity of the argument. Therefore, it is possible that a range of intensity of arguments may be captured in the measurement, as it is not possible to know if respondents were including items that are more in line with discussing different points of view, deciding to agree to disagree, or in a more aggressive manner. Further work investigating both the frequency and the intensity of arguments may add to this literature and provide for better planner recommendations for working with couples.

Conclusion

Results from this study suggest that a wife’s relative income contribution and her psychological well-being may significantly impact marital happiness, and consequently, a couple’s ability to progress toward their financial goals and improve or maintain their financial well-being. These results add to the literature about income and marital happiness by supporting the idea that the source of income and relative contributions of income may be influential on marital happiness.

With the increased income contribution by women nationwide, it is important to give consideration to shifting relationship dynamics and the role that stress may play in a marriage. Importantly, this study only focused on a wife’s marital happiness. The study did not explore how this strain may be impacting the husband. Additionally, a wife’s self-esteem and the presence of marital arguments, most notably about money, were found to both significantly and negatively impact marital happiness. Consequently, an understanding of a client’s psychological state and awareness of marital discord is critically important to a financial planner’s ability to serve their clients effectively and efficiently.

Nearly all financial planners are aware that their jobs involve more than just numbers. As hypothesized from Becker’s (1976) work, psychological factors and relational barriers impact marital happiness of women. This study supports the assertion that financial planners may be better able to serve their clients by connecting in a more personal way. Specifically, practitioners may be able to assist their clients by understanding their clients better and presenting recommendations and advice in the context of psychological and relational barriers, such as self-esteem, perceived locus of control, and frequency of spousal arguments. If a financial planner is aware of one of more of these barriers, and he or she addresses these barriers when making recommendations, clients may be more receptive to the advice, as they will feel the suggestions are more applicable and personal to them.

Listening for cues of low self-esteem (such as comments about constant failure or being no good), cues of low levels of perceived control (such as reliance on luck or good fortune to meet goals), and indicators of high relational conflict (such as arguments between spouses during planning sessions or visible disengagement between spouses) may indicate lower levels of marital happiness. As a result, we are suggesting that the married couple’s relationship may dissipate. If this occurs, the financial planner could be caught in a problematic position. The financial planner may be fired if the relationship fails, assets are divided, and the individuals go their separate ways.

Financial planners should acknowledge factors that contribute to marital happiness when working with married clients. Income and finances play a role in producing utility (Becker 1976), but other factors also contribute to marital happiness. If a client demonstrates sufficient barriers—such as marital unhappiness—that are impeding their financial progress, it may be necessary to refer clients to a financial therapist or mental health professional. This is particularly true when a financial planner is hesitant to address these issue directly. The successful referral for clients struggling with psychological and/or relationship issues benefits both the client’s relationship and the financial planning process.

As shown here, finances play a role in determining marital happiness, and conversely, marital happiness and stability influence a client’s long-term financial plan. An understanding of how a client’s relative income, as measured by family income contribution percentage, may impact marital happiness can be especially important in situations where women earn more than their husband. Certainly, addressing psychological issues without proper training may be dangerous and potentially unethical. However, financial planners should be aware of a client’s emotions and psychological state of mind, referring to a therapist when a client needs attention outside of their skill set.

References

Amato, Paul R., Alan Booth, David R. Johnson, and Stacy J. Rogers. 2007. Alone Together: How Marriage in America is Changing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Becker, Gary S. 1976. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2007. “The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?” Academy of Management Perspectives 21 (1): 7–23.

Britt, Sonya L., and Sandra J. Huston. 2012. “The Role of Money Arguments in Marriage.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 33 (4): 464–476.

Cutrona, Carolyn. E., Daniel W. Russell, W. Todd Abraham, Kelli A. Gardner, Janet N. Melby, Chalandra Bryant, and Rand D. Conger. 2003. “Neighborhood Context and Financial Strain as Predictors of Marital Interaction and Marital Quality in African American Couples.” Personal Relationships 10 (3): 389–409.

Dakin, John, and Richard Wampler. 2008. “Money Doesn’t Buy Happiness, but It Helps: Marital Satisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Demographic Differences between Low- and Middle-Income Clinic Couples.” The American Journal of Family Therapy 36 (4): 300–311.

Dew, Jeffrey, Sonya L. Britt, and Sandra J. Huston. 2012. “Examining the Relationship Between Financial Issues and Divorce.” Family Relations 61 (4): 615–628.

Furdyna, Holly E., M. Belinda Tucker, and Angela D. James. 2008. “Relative Spousal Earnings and Marital Happiness among African American and White Women.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70 (2): 332–344.

Grob, Alexander, Todd D. Little, and Brigitte Wanner. 1993. “Control Judgements across the Lifespan.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 23 (4): 833–854.

Kalmijn, Matthijs, Anneke Loeve, and Dorien Manting. 2007. “Income Dynamics in Couples and the Dissolution of Marriage and Cohabitation. Demography 44 (1): 159–179.

Karney, Benjamin R., and Thomas N. Bradbury. 1995. “The Longitudinal Course of Marital Quality and Stability: A Review of Theory, Method, and Research.” Psychological Bulletin 118 (1): 3–34.

Kinder, George. 2014. “Life Planning: Creator of Entrepreneurial Endeavor.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (8): 33–34.

Lupton, Joseph P., and James P. Smith, 2003. “Marriage, Assets and Savings.” In Marriage and the Economy: Theory and Evidence from Advanced Industrial Societies, edited by Shoshana A. Grossbard, 129–152. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Murray, Sandra L., Paul Rose, Gina M. Bellavia, John G. Holmes, and Anna Garrett Kusche. 2002. “When Rejection Stings: How Self-Esteem Constrains Relationship-Enhancing Processes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83 (3): 556–573.

Myers, Scott M., and Alan Booth. 1999. “Marital Strains and Marital Quality: The Role of High and Low Locus of Control.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 61 (2): 423–436.

National Longitudinal Surveys. 2014. “NLSY79 Appendix 21: Attitudinal Scales.” www.nlsinfo.org.

Nyqvist, Fredrica, Anna K. Forsman, and Mima Cattan. 2013. “A Comparison of Older Workers’ and Retired Older People’s Social Capital and Sense of Mastery.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 41 (8): 792–798.

Oggins, Jean. 2003. “Topics of Marital Disagreement among African-American and Euro-American Newlyweds.” Psychological Reports 92 (2): 419–425.

Oppenheimer, Valerie K. 1997. “Women’s Employment and the Gain to Marriage: The Specialization and Trading Model.” Annual Review of Sociology 23 (1): 431–453.

Pearlin, Leonard I., Morton A. Lieberman, Elizabeth A. Menaghan, and Joseph T. Mullen. 1981. “The Stress Process.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22 (12): 337–356.

Raley, Sara B., Marybeth J. Mattingly, and Suzanne M. Bianchi. 2006. “How Dual Are Dual-Income Couples? Documenting Change from 1970 to 2001.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68 (1): 11–28.

Rauer, Amy J., Benjamin R. Karney, Cynthia W. Garvan, and Wei Hou. 2008. “Relationship Risks in Context: A Cumulative Risk Approach to Understanding Relationship Satisfaction.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70 (5): 1122–1135.

Robins, Richard W., and Kali H. Trzesniewski. 2005. “Self-Esteem Development across the Lifespan.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14 (3): 158–162.

Rogers, Stacy J. 2004. “Dollars, Dependency, and Divorce: Four Perspectives on the Role of Wives’ Income.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (1): 59–74.

Rogers, Stacy J., and Danelle D. DeBoer. 2001. “Changes in Wives’ Income: Effects on Marital Happiness, Psychological Well-Being, and the Risk of Divorce.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63 (2): 458–472.

Rosenberg, Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sayer, Liana C., and Suzanne Bianchi. 2000. “Women’s Economic Independence and the Probability of Divorce: A Review and Reexamination.” Journal of Family Issues 21 (7): 906–943.

Shackelford, Todd K. 2001. ”Self-Esteem in Marriage.” Personality and Individual Differences 30 (3): 371–390.

Solaimani, Fatemeh. 2014. “Comparing Control Locus and Quality of Life in Couples with High and Low Marital Satisfaction.” Journal of Life Science and Biomedicine 4 (2): 131–134.

Stanley, Scott M., Howard J. Markman, and Sarah W. Whitton. 2002. “Communication, Conflict, and Commitment: Insights on the Foundations of Relationship Success from a National Survey. Family Process 41 (4): 659–675.

Vespa, Jonathan, and Matthew A. Painter, II. 2011. “Cohabitation History, Marriage, and Wealth Accumulation.” Demography 48 (3): 983–1004.

Xu, Anqi, Yuanting Zhang, and Paul R. Amato. 2011. “A Comparison of Divorce Risk Models in China and the United States.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 42 (2): 289–295.

Citation

Wilmarth, Melissa, Martin C. Seay, and Sonya L. Britt. 2015. “Psychology, Money, and Marital Arguments: What Shapes a Woman’s Happiness Level?” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (8): 42–48.