Journal of Financial Planning: November 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Financial wellness includes both objective financial health (e.g., debt, savings, budgeting) and subjective financial well-being (e.g., perceived control, satisfaction, stress).

- The study introduces the financial wellness quadrants of dangerous (low financial health, low financial well-being), overconfident (low financial health, high financial well-being), pessimistic (high financial health, low financial well-being), and content (high financial health, high financial well-being).

- Only 38 percent of individuals fall into the ideal content quadrant.

- Financial satisfaction and physical health are strong predictors of better financial wellness outcomes.

- Homeownership, higher income, and being retired are positively associated with high financial wellness.

- Financial planners can use the wellness quadrants to understand how people who look financially secure on paper could be struggling to achieve wellness due to their perceptions. Equally important, the quadrants point toward elements of overconfidence and potential lack of motivation because of high perceived well-being but low actual financial health.

- A systemic approach to financial planning will evaluate clients’ situations more carefully and from multiple perspectives to make recommendations that are implemented and create lasting relationships.

Sonya Lutter, Ph.D., is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® professional and licensed marriage and family therapist. She is the director of financial health and wellness at Texas Tech, where she leads curriculum and continuing education in the areas of financial psychology, financial therapy, and financial behavior. She is also the executive director of the Institute for Systemic Financial Professionals.

Van Dinh, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of finance at School of Business and Economics, University of Wisconsin, Superior. She has led international projects to produce personal finance handbooks for teaching youth and women in rural Asia. She also led a major financial education initiative for 8,000 college students in Vietnam.

NOTE: Click the images below for PDF versions.

The subjective and objective elements of financial wellness are now well-documented (e.g., Brüggen et al. 2017; CFPB 2015; Netemeyer et al. 2018). The objective of the CFP Board’s longitudinal study on outcomes associated with the use of financial planning services is centered around such a framework that includes objective financial health (i.e., resource management) and subjective features such as one’s psychological–social condition and well-being (Koochel et al. 2023).

Despite increasing awareness and efforts to improve financial wellness, many U.S. consumers need help with financial issues they are experiencing. Currently, less than one-third of Americans are considered financially healthy, leaving 69 percent either financially coping or vulnerable, according to Financial Health Network’s 2023 Report (Cepa et al. 2023). The Federal Reserve further reports that one in four adults cannot cover an unexpected $400 emergency expense (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2024). The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB 2023) recently showed that 37.8 percent of households have difficulty paying at least one bill or expense. These statistics suggest a pressing issue in the financial wellness of consumers. The current paper presents the financial wellness quadrants of dangerous (low financial health, low financial well-being), overconfident (low financial health, high financial well-being), pessimistic (high financial health, low financial well-being), and content (high financial health, high financial well-being) as illustrated in Figure 1.

Literature Review

Joo (2008) appears to be one of the first researchers to conceptualize financial wellness as a comprehensive measure of subjective perception, behavior, objective measures, and satisfaction contributing to overall well-being. Koochel et al. (2023) expanded this perspective, suggesting that financial wellness includes an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding their financial situation, emphasizing behavioral and psychological dimensions.

Financial health is often measured through objective financial indicators, such as liquidity ratios, debt-to-asset ratios, and credit scores (Baek and DeVaney 2004; Bhutta 2014; Parker et al. 2016). Financial health emphasizes financial resilience, or the ability to withstand financial shocks, by assessing tangible assets and liabilities and can be gauged through metrics like recent delinquencies, unsecured debt levels, and asset holdings to provide a snapshot of an individual’s economic stability and capacity to manage resources effectively (Bhutta 2014; Brevoort et al. 2017; Dobbie et al. 2017; Huston 2015; Parker et al. 2016). The Financial Health Network developed a comprehensive measure of financial health, which combines the results of financial activities: spending, saving, borrowing, and planning of individuals (Parker et al. 2016). Gallup (2018) views financial health in terms of financial security and control, where financial security involves navigating unexpected shocks and financial control measures an individual’s confidence in managing their financial matters.

Financial well-being is often more subjective, focusing on individuals’ perceptions of their financial situation and ability to achieve financial objectives (CFPB 2015; Brüggen et al. 2017; Salignac et al. 2020). The CFPB conceptualized financial well-being as meeting current and future financial obligations while maintaining a desirable standard of living (CFPB 2015). Studies have found that individuals with higher financial well-being are more likely to report lower levels of financial stress and greater satisfaction with their financial circumstances (Ranta et al. 2024). Financial well-being must be understood in context, particularly for vulnerable groups, where social connection and cultural values shape how people report well-being. (Diener and Seligman 2004; Salignac et al. 2020; Snow et al. 2016).

Early researchers have long categorized consumers into meaningful groups based on shared characteristics, such as consumer decision-making styles (Sproles and Kendall 1986), price perceptions (Lichtenstein et al. 1993), or susceptibility to interpersonal influence (Bearden et al. 1989). More recently, Allgood and Walstad (2016) classified individuals into four financial literacy groups, high perceived / high actual, high perceived / low actual, low perceived / high actual, and low perceived / low actual, to explore their effects on financial behavior, highlighting how cognitive and psychological dimensions interact. Similarly, Iannello et al. (2021) grouped participants by tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity (anxious, comfortable, black-and-white thinkers, flexible thinkers) to analyze the relationship between subjective financial well-being and overall well-being. This study adopts a similar quadrant-based approach to categorize consumers into four financial wellness segments, aiming to support more targeted interventions and recommendations for financial planners, educators, and policymakers. Specifically, it defines quadrants as dangerous (low financial health, low financial well-being), overconfident (low financial health, high financial well-being), pessimistic (high financial health, low financial well-being), and content (high financial health, high financial well-being).

Factors Impacting Financial Wellness

Research has shown various factors influencing financial wellness, financial health, and financial well-being, including financial satisfaction, physical health, and demographic characteristics. These factors are critical in impacting individuals’ financial stability and perceptions of financial security.

Financial satisfaction is a part of financial wellness and is often used as a proxy for financial well-being. Gerrans et al. (2014) argued that financial satisfaction impacts financial wellness, which shows how individuals perceive their financial situation. Previous research has found that financial satisfaction is positively associated with financial behaviors like saving and budgeting, which enhance financial stability (Joo 2008; Ranta et al. 2024). Financial satisfaction was also found to strengthen the relationship between financial behaviors and general well-being, suggesting that financial contentment is part of overall life satisfaction (Gerrans et al. 2014).

Physical health has also been shown to correlate with financial wellness. Financial stress can lead to physical and mental health issues, creating a feedback loop in which poor health further strains financial resources (Prawitz et al. 2006). Kim et al. (2005) found that many individuals experiencing higher healthcare costs reduced their retirement savings contributions and cut back substantially on other savings types. Research has documented that those individuals experiencing better health are associated with lower financial distress, higher financial well-being, and better retention in the debt management program (O’Neill et al. 2006). Individuals having high financial stress are more likely to report poor physical health, which can reduce their ability to work, thus affecting their income and financial stability (Salignac et al. 2020). Kim and Lee (2024) also noted that individuals with disabilities experience significantly lower financial well-being compared to those without disabilities.

Demographic factors such as gender, age, income, education, household size, and homeownership also significantly impact financial wellness. Gender impacts financial wellness, with women often having lower financial well-being due to their lower education, income, and financial skills (Gonçalves et al. 2021). In addition, Prakash and Hawldar (2024) suggested that financial wellness programs in tech companies should be tailored based on job roles and gender rather than using a standardized approach. Age can also impact financial wellness perception; youth view financial well-being as maintaining their lifestyle, achieving desired goals, and gaining financial freedom, while older groups focus on maintaining and achieving a lifestyle in the present and future (Riitsalu et al. 2024). Higher income and education levels are often related to better financial health, as they enable individuals to accumulate assets and reduce debt (Brüggen et al. 2017; CFPB 2015; Delafrooz and Paim 2011; Montalto et al. 2019). Young adults, especially college students, face unique financial challenges due to student loans and limited income, which affect their financial wellness and stress levels (Ismail and Amiruddin Zaki 2019; Montalto et al. 2019). In addition to personal and demographic factors, financial wellness can be impacted by contextual factors such as financial socialization, country economic indicators, and cultural influences (Garg et al. 2024; Parker et al. 2016). To the extent the data allow, the analysis tested how known predictors of financial wellness can be further predicted to fall within a specific quadrant of financial wellness: dangerous (low health, low well-being), overconfident (low health, high well-being), pessimistic (high health, low well-being), and content (high health, high well-being).

Methods

Data

This study used panel data from the Understanding America Study (UAS), specifically the Financial Health Network’s U.S. Financial Health Pulse Survey (2021–2023), which included 13,179 pooled participants (4,393 panel participants). The dataset, administered by the University of Southern California’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, offers a nationally representative, high-quality resource that tracks both objective financial health and subjective financial well-being among U.S. adults over multiple years. The survey waves from 2021–2023 (UAS 385, 453, and 543) include extensive measures of demographics, financial satisfaction, financial behaviors, income, spending, savings, debt, and experiences with economic shocks such as inflation and student loan forbearance. The UAS data was chosen over more commonly used datasets because it combines high-frequency panel data with suitable proxies for financial health and financial well-being. The repeated observations across years make it possible to capture transitions among financial wellness quadrants, offering insights into possible causal inferences that cross-sectional surveys cannot. Given the study’s goal to explore both subjective (well-being) and objective (health) dimensions in a longitudinal framework, the UAS is well-suited to deliver an understanding of holistic financial wellness over time.

Financial Wellness

The outcome of financial wellness has two components of financial health and financial well-being. Financial health includes four critical dimensions of spending, saving, borrowing, and planning to use eight survey questions (two per dimension), such as spending less than income, having sufficient short-term and long-term savings, managing debt responsibly, and maintaining forward-looking financial plans (Parker et al. 2016). An average was taken across all indicators, yielding a comprehensive financial health score ranging from 0 to 100. Using ranges defined by Parker et al. (2016) as “financially healthy,” respondents who scored 80 or higher were classified as having high financial health; otherwise, low financial health if their score was below 80. Financial well-being was measured with the shortened, five-question CFPB financial well-being assessment, producing a score between 0 and 100 (CFPB 2015). Given that no cutoff scores exist, financial well-being was categorized with scores below 50 as low financial well-being and 50 or above as high financial well-being.

Financial wellness was divided into four quadrants by assessing two main dimensions of financial health and financial well-being, each classified into low and high categories. These classifications yield the distinct financial wellness quadrants of dangerous (low health, low well-being), overconfident (low health, high well-being), pessimistic (high health, low well-being), and content (high health, high well-being).

Independent Variables

Based on the review of literature, this descriptive report captures a number of financial satisfactions, health, and demographic data used to predict how respondents fall into one of the four quadrants. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of satisfaction with their current economic situation on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from extremely satisfied to not at all satisfied. These categories were then grouped into not at all / not very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, and very/extremely satisfied.

Respondents were asked to self-rate their physical health with options including excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Physical health was also reverse-coded with the two lowest categories of poor and fair combined due to low response rates. Household living situation was captured dichotomously with whether they owned their home or not.

Demographic data included race (White versus non-White), gender (male versus female), age (ranging from 18–99), marital status (married, divorced, never married, and other), education (less than a bachelor’s, a bachelor’s degree, and more than a bachelor’s), household income (categories of less than $50,000, $50,000–$75,000, $75,000–$150,000, and more than $150,000), and number of household members (ranging from zero to nine), and retired status (retired versus not).

Model Specification and Analyses

A multinomial logistic regression model was employed to predict the probability of an individual being classified into each financial wellness quadrant relative to a baseline category. The independent variables included in the multinomial logistic regression models were guided by prior research on financial wellness, financial health, and financial well-being. Financial satisfaction, physical health status, and living situation have been repeatedly shown to predict both objective and subjective aspects of financial wellness (CFPB 2015; Gerrans et al. 2014; Joo 2008). Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race, marital status, education, household income, household size, and retirement status, were included to account for structural and socioeconomic differences that shape individuals’ financial behaviors and perceptions, consistent with the previous frameworks (Brüggen et al. 2017; Gonçalves et al. 2021; Montalto et al. 2019). In addition, the survey year was added to control for time-specific effects and macroeconomic changes (e.g., inflation, policy interventions) that could influence financial wellness. These independent variables provide a comprehensive model that captures both individual-level and contextual factors influencing placement within the financial wellness quadrants.

Prior to running the multinomial logistic regression, multicollinearity among the independent variables was evaluated using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs). The analysis showed no evidence of problematic multicollinearity, with a mean VIF of 1.64 and all individual VIF values well below the conventional cutoff of 10. Both fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models were estimated and compared using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Likelihood Ratio (LR) test. The random effects model demonstrated a better fit, with lower AIC (19,492.74 versus 19,583.53) and BIC (19,986.84 versus 20,032.71) values. Additionally, the LR test confirmed a better model fit for the RE model (LR Chi²(6) = 102.79, p <.001). Given these results, the random effect model is selected for further analysis.

In this context, an individual’s likelihood of falling into one of four financial wellness quadrants is modeled in a random effect model as follows:

This study assumes the standard independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) condition, meaning the four financial wellness quadrants (dangerous, overconfident, pessimistic, and content) are conceptually distinct and mutually exclusive categories. Each quadrant combines different levels of financial health (objective measures) and financial well-being (subjective measures), and individuals cannot simultaneously belong to more than one quadrant. Potential sources of bias include self-reported measures, which may be affected by recall issues and unobserved confounders that were not included in the dataset. To mitigate these concerns, the model incorporated random effects to account for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity and year-fixed effects to control for macroeconomic changes. Robust standard errors were applied to address potential heteroskedasticity. Bootstrapping with 1,000 replications was used as a sensitivity check to ensure the stability of the parameter estimates. The relative risk ratios were consistent across the baseline, robust, and bootstrapped models, reinforcing confidence in the validity of the findings. For interpretability, the study reports the average marginal effects from the robust standard errors model in the results section.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

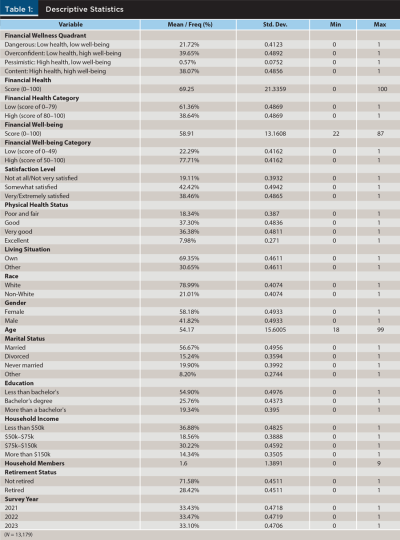

Table 1 provides summary statistics for the sample. When divided into wellness quadrants, around 21.72 percent were classified in the dangerous quadrant of low health, low well-being, while 39.65 percent were content with high health, high well-being. This distribution reflects a range of financial wellness levels, with nearly half of the respondents facing some financial challenges despite many feeling financially well.

The sample was predominantly White (78.99 percent) and married (56.67 percent) with 58.18 percent females and 41.82 percent males. The average age of respondents was 54.17 years, with household sizes averaging 1.6 members. About half of the sample (54.90 percent) reported having less than a bachelor’s degree, with income fairly well distributed across categories. About 28.42 percent of the sample was retired, which may affect financial wellness.

The majority of respondents are somewhat satisfied (42.42 percent) or very satisfied (38.46 percent) with their financial circumstances, with 19.11 percent reporting being not at all satisfied or not very satisfied. Furthermore, most respondents reported good (37.30 percent) or very good (36.38 percent) health, while 18.34 percent indicated poor or fair health. A significant portion of the sample owns their homes (69.35 percent), while 30.65 percent rent or live with others. This high level of home ownership may contribute positively to financial wellness, given the potential financial security associated with property ownership.

Regression Analysis

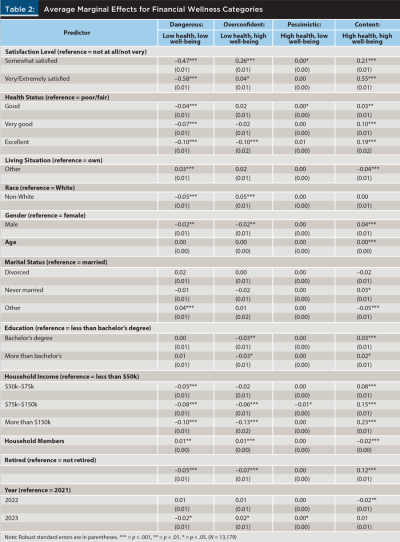

The multivariate analysis involved average marginal effects (AMEs) with robust standard errors to reflect the absolute change in probability for each quadrant of financial wellness (see Table 2). Individuals who are somewhat satisfied show a 47-percentage-point decrease in the probability of being in the dangerous quadrant (low health, low well-being), a 26-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the overconfident quadrant (low health, high well-being) and a 21-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the content quadrant (high health, high well-being). Those who are very/extremely satisfied see an even larger 58-percentage-point decrease in the probability of being in the dangerous quadrant, 55-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the content quadrant, showing the strong association between satisfaction and better financial wellness.

In terms of physical health, individuals in good health show a four-percentage-point decrease in the probability of being in the dangerous quadrant (low health, low well-being), a three-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the content quadrant (high health, high well-being), while those in excellent health have a 10-percentage-point decrease in both the dangerous and overconfident quadrants, and 19-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the content quadrant. Interestingly, excellent health reduces the probability of being in the overconfident quadrant (low health, high well-being) by 10 percentage points. Living situation has a smaller effect; for individuals in the other category, the probability of being in the dangerous quadrant increases by three percentage points while the probability of being in the content quadrant decreases by almost four percentage points.

Regarding demographic characteristics, non-White individuals had a five-percentage-point decrease in the probability of being in the dangerous quadrant of low health, low well-being, and a five-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the overconfident quadrant with low health, high well-being. However, this effect was not statistically significant in the other categories. For gender, males were two percentage points less likely to be in the dangerous or overconfident quadrants, but four percentage points more likely to be in content quadrant. Income levels showed a strong positive relationship with being in the content quadrant; individuals with incomes between $75,000–$150,000 and above $150,000 were 15- and 23-percentage points more likely to be in this category, respectively. Conversely, household size had a negative impact on being in the content quadrant, where each additional household member decreased the probability by two percentage points. Retirement status also had a significant effect, with retired individuals having a five-percentage-point decrease, seven-percentage-point decrease, and a 12-percentage-point increase in the probability of being in the dangerous, overconfident, and content quadrants, respectively. Other variables, such as age, marital status, education, or year, did not appear to have significant effects on the likelihood of falling into the different financial wellness quadrants.

Discussion

This study examined various factors predicting financial wellness, utilizing panel data to capture both objective and subjective dimensions of financial wellness. The reliance on self-reported data for physical health status introduces potential biases due to respondents’ subjective perceptions and recall issues. Yet, the outcome itself is partially based on how a person feels about their situation. Research supports that subjective evaluation is relatively accurate and that subjective evaluations are oftentimes more important in predicting behavior change (Brüggen et al. 2017; Netemeyer et al. 2018).

Another limitation is collapsing some of the demographic categories, like race, marital status, income, and education, due to small sample sizes in some of the categories. Because of this process, variations among the groups may very well have been missed. Qualitative data would be especially useful in identifying the nuances associated with how underrepresented groups fall into the financial wellness quadrants.

In light of the limitations, key findings highlight the role of financial satisfaction, physical health, and living status in shaping overall financial wellness, suggesting that individuals who experience higher levels of satisfaction, good physical health, and owning a house report stronger financial wellness outcomes.

Demographic factors such as income, household size, race, and gender further impact financial wellness levels and predict the financial wellness quadrants. After controlling for socioeconomic disadvantages, the results suggest that lower income, education, or homeownership, non-White individuals may have unobserved resilience factors, social support, or financial optimism that reduce the likelihood of being in the lowest quadrant. White respondents appear to be more congruent in their perceptions versus objective reality—i.e., they seem to know they have low health as evidenced by their lower self-assessed well-being. Similarly, it is possible that women may have higher resilience or coping strategies in the face of poor financial health. As such, financial education and planning can be more specific to meet the needs of various groups. Furthermore, future research should include measures of financial literacy, mental health, and financial access to determine how that influences the results.

Implications for Financial Planners

Financial planning approaches focused exclusively on financial health (e.g., assets, debt, financial ratios) are not sufficient in improving financial wellness. Financial well-being (i.e., a sense of control and satisfaction) can make the difference in overall financial wellness. Financial planners must recognize that a client may exhibit strong objective financial health while still feeling pessimistic or financially insecure.

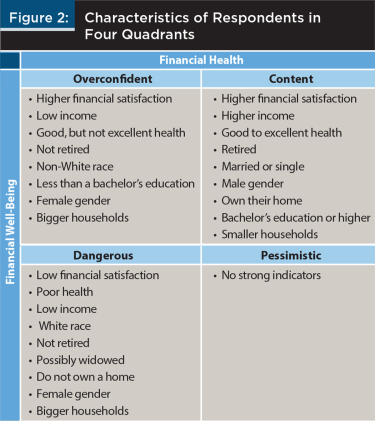

The financial wellness quadrants of dangerous, overconfident, pessimistic, and content offer a practical framework for planners to tailor strategies based on where clients fall. Figure 2 highlights respondent characteristics that are statistically associated with falling into the four quadrants.

In application, clients in the overconfident quadrant of low financial health, high well-being may underestimate financial risks and require guidance to align perceptions with reality. In contrast, those in the pessimistic group of high financial health, low well-being may benefit more from emotional reassurance, behavioral coaching, or stress-reduction interventions than technical financial changes. Financial planners should consider adopting behavioral finance approaches and coaching techniques to better support these clients. Collaborating with other professionals, such as healthcare providers, mental health counselors, or housing advocates, may be a strategic way to support client wellness beyond traditional financial advice.

Citation

Lutter, Sonya, and Van Dinh. 2025. “Categorizing Financial Wellness into Meaningful Quadrants.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (11): 76–89.

References

Allgood, Sam, and William B. Walstad. 2016. “The Effects of Perceived and Actual Financial Literacy on Financial Behaviors.” Economic Inquiry 54 (1): 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12255.

Baek, Eunyoung, and Sharon A. DeVaney. 2004. “Assessing the Baby Boomers’ Financial Wellness Using Financial Ratios and a Subjective Measure.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 32 (4): 321–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X04263826.

Bearden, William O., Richard G. Netemeyer, and Jesse E. Teel. 1989. “Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (4): 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1086/209186.

Bhutta, Neil. 2014. “Payday Loans and Consumer Financial Health.” Journal of Banking and Finance 47 (1): 230–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.04.024.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2024. “Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2023.” https://doi.org/10.17016/8960.

Brevoort, Kenneth, Daniel Grodzicki, and Martin B. Hackmann. 2017. “Medicaid and Financial Health.” National Bureau of Economic Research. www.nber.org/papers/w24002.

Brüggen, Elisabeth C., Jens Hogreve, Maria Holmlund, Sertan Kabadayi, and Martin Löfgren. 2017. “Financial Well-Being: A Conceptualization and Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 79 (October): 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013.

Cepa, Kennan, Wanjira Chege, Necati Celik, Andrew Warren, and Riya Patil. 2023. 2023 U.S. Trends Report: Rising Financial Vulnerability in America. Financial Health Network.

CFPB. 2015. “Financial Well-Being: The Goal of Financial Education.” Retrieved from https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_report_financial-well-being.pdf.

CFPB. 2023. “Making Ends Meet in 2023: Insights from the Making Ends Meet Survey” (Publication No. 2023-8). Retrieved from https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_making-ends-meet-in-2023_report_2023-12.pdf.

Delafrooz, Narges, and Laily H. Paim. 2011. “Determinants of Financial Wellness Among Malaysia Workers.” African Journal of Business Management 5 (24): 10092–10100. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajbm10.1267.

Diener, Ed, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2004. “Beyond Money: Toward an Economy of Well-Being.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 5 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x.

Dobbie, Will, Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, and Crystal S. Yang. 2017. “Consumer Bankruptcy and Financial Health.” Review of Economics and Statistics 99 (5): 853–869. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00669.

Gallup. 2018. “Gallup Global Financial Health Study Key Findings and Results.” https://news.gallup.com/reports/233399/gallup-global-financial-health-study-2018.aspx.

Garg, Nishant, Pushpendra Priyadarshi, and Ashish Malik. 2024. “Financial Well-Being: An Integrated Framework, Operationalization, and Future Research Agenda.” Consumer Behaviour 23: 3194–3212. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2372.

Gerrans, Paul, Craig Speelman, and Guillermo Campitelli. 2014. “The Relationship Between Personal Financial Wellness and Financial Well-Being: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 35 (2): 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z.

Gonçalves, Virginia Nicolau, Mateus Canniatti Ponchio, and Roberta Gabriela Basílio. 2021. “Women’s Financial Well-Being: A Systematic Literature Review and Directions for Future Research.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: 824–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12673.

Huston, Sandra J. 2015. “Using a Financial Health Model to Provide Context for Financial Literacy Education Research: A Commentary.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 26 (1): 102–104.

Iannello, Paola, Angela Sorgente, Margherita Lanz, and Alessandro Antonietti. 2021. “Financial Well-Being and Its Relationship with Subjective and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: Testing the Moderating Effect of Individual Differences.” Journal of Happiness Studies 22 (3): 1385–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00277-x.

Ismail, Nurazleena, and Nur Damia’ Amiruddin Zaki. 2019. “Does Financial Literacy and Financial Stress Effect Financial Wellness?” International Journal of Modern Trends in Social Sciences July: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.35631/ijmtss.28001.

Joo, So-hyun. 2008. “Personal Financial Wellness.” In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Edited by Jing Xiao. Springer: 21–33.

Kim, Jinhee, Jasook Kwon, and Elaine A. Anderson. 2005. “Factors Related to Retirement Confidence: Retirement Preparation and Workplace Financial Education.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 16 (2): 77–89.

Kim, Kyoung Tae, and Jonghee Lee. 2024. “Unlocking Financial Well-Being for People With Disabilities: The Importance of Financial Knowledge and Socialization Within the Family Context.” SAGE Open 12 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241253564

Koochel, Emily, Sonya Lutter, and Stuart Heckman. 2023. “Consumer Financial Wellness: A Definition and Framework.” Certified Financial Planning Board. www.cfp.net/-/media/files/cfp-board/initiatives/impact-study/consumer-financial-wellness-a-definition-and-framework.pdf.

Lichtenstein, Donald R., Nancy M. Ridgway, and Richard G. Netemeyer. 1993. “Price Perceptions and Consumer Shopping Behavior: A Field Study.” Journal of Marketing Research 30 (2): 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379303000208.

Montalto, Catherine P., Erica L. Phillips, Anne McDaniel, and Amanda R. Baker. 2019. “College Student Financial Wellness: Student Loans and Beyond.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9593-4.

Netemeyer, Richard G., David Warmath, Daniel Fernandes, and John G. Lynch Jr. 2018. “How Am I Doing? Perceived Financial Well-being, Its Potential Antecedents, and Its Relation to Overall Well-being.” Journal of Consumer Research 45 (1): 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109.

O’Neill, Barbara, Aimee D. Prawitz, Benoit Sorhaindo, Jinhee Kim, and E. Thomas Garman. 2006. “Changes in Health, Negative Financial Events, and Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being for Debt Management Program Clients.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 17 (2): 46–63. http://ssrn.com/abstract=223212146.

Parker, Sarah, Nancy Castillo, Thea Garon, and Rob Levy. 2016. “Eight Ways to Measure Financial Health.” Center for Financial Services Innovation. https://cfsi-innovation-files-2018.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/09212818/Consumer-FinHealth-Metrics-FINAL_May.pdf.

Prakash, Nisha, and Aparna Hawaldar. 2024. “Investigating the Determinants of Financial Well-Being: A SEM Approach.” Business Perspectives and Research 12 (1): 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/22785337221148253.

Prawitz, Aimee, E. Thomas Garman, Benoit Sorhaindo, Barbara O’Neill, Jinhee Kim, and Patricia Drentea. 2006. “Incharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 17 (1): 34–50. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2239338.

Ranta, Mette, Lijun Li, Rimantas Vosylis, et al. 2024. “Financial Loss and Financial Well-Being of Emerging Adults during COVID-19: The Limitations of Psychological Resilience.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning April, JFCP-2022-0088.R1. https://doi.org/10.1891/jfcp-2022-0088.

Riitsalu, Leonore, Rene Sulg, Henri Lindal, Marvi Remmik, and Kristiina Vain. 2024. “From Security to Freedom—The Meaning of Financial Well-Being Changes with Age.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 45 (1): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-023-09886-z.

Salignac, Fanny, Myra Hamilton, Jack Noone, Axelle Marjolin, and Kristy Muir. 2020. “Conceptualizing Financial Wellbeing: An Ecological Life-Course Approach.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (5): 1581–1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00145-3.

Snow, Stephen, Dhaval Vyas, and Margot Brereton. 2016. “Sharing, Saving, and Living Well on Less: Supporting Social Connectedness to Mitigate Financial Hardship.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 33 (5): 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2016.1243846.

Sproles, George B., and Elizabeth L. Kendall. 1986. “A Methodology for Profiling Consumers’ Decision-Making Styles.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 20 (2): 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1986.tb00382.x.