Journal of Financial Planning: May 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Elections disturb expectations of the future and impact financial plans. This study investigates how an individual’s views of the future change in response to changes in political leadership, whether the individuals act based upon these leadership changes, and if financial attitudes are affected.

- Individuals make decisions by weighing expected benefits of present and future actions. When elections shift projections, weighted benefits change as do feelings of financial well-being and self-efficacy. Related research shows that political affiliation is tied to a wide range of emotions, projections, and actions, necessitating a greater understanding of how the emotions surrounding an election can translate into decision-making.

- The results of this paper show that although economic and financial projections shift dramatically following an election, there is only a slight impact on financial well-being and financial self-efficacy and no measurable impact on stock allocation in a portfolio.

- Financial planners can take several actions to prepare clients or help them overcome desires to make reactionary changes to their financial plans. Strategies discussed include asking clients to give advice to someone else in a similar situation, having the client write a letter to their future selves, referencing investment policy statements, and considering the minimal impact elections generally have on day-to-day life.

Blake Gray, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning department at Kansas State University. He is also the faculty consultant for Powercat Financial at Kansas State.

Thomas Crandall, CFP®, CFA, CAIA, CMT, is a Minneapolis-based investment professional focusing on asset allocation and long-term financial planning, and a Ph.D. student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University.

Donovan Sanchez, CFP®, is a personal financial planning instructor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a senior financial planner with Model Wealth, Inc., and a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions, feedback, and insightfulness of Russell Brockett, who was integral in filling many holes in this idea; Dr. Sarah Asebedo, whose mentorship is still felt; and the School of Financial Planning and Center for Financial Responsibility at Texas Tech University for funding of the survey.

Click HERE to read this article in the DIGITAL EDITION.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click the images below for PDF versions.

Financial planners help their clients use information, logic, and analysis to balance the future and present. However, individuals filter perceptions through experience and worldview, including through the lens of their political affiliation (Gerber and Huber 2009). The political atmosphere in the United States has become increasingly charged since the 1980s (Mian 2023), and with political affiliation influencing economic expectations (Evans and Andersen 2006) and happiness (Jackson 2019), the opportunity for increased anxiety and sub-optimal decision-making before and in the wake of an election needs evaluation.

Presidential elections can be stressful, particularly for those of different political affiliations (Majumder et al. 2017). Stress and anxiety increase as individuals attach higher levels of importance to politics (Pitcho-Prelorentzos et al. 2018) and have greater political engagement (Smith et al. 2023). Anxiety and cynicism around elections can have rational roots, but historically, there is little to no consistency between political leadership and near-term economic or stock market outcomes (Santa-Clara and Valkanov 2003). Over time, the stock market and the economy have fared well regardless of the political party in control and during leadership changes. Nevertheless, around presidential elections, clients articulate feelings like, “If [the opposing candidate] wins the election, I am moving out of this country,” or “I want to take all my money out of the stock market because [the opposing candidate] won the election.”

During the election season, it can be particularly important for planners to understand and assuage election-related anxiety. A key to helping clients navigate unease through the political season may be found in understanding how individuals respond to external stimuli. Hedonic adaptation suggests that individuals have temporary reactions to stimuli before eventually returning to baseline levels. Anxiety often crescendos right before and immediately after the event (e.g., the election) while the individual is in reaction mode but before they can rationally assess the new environment (Smith et al. 2023). The key to supporting individuals is in the lead-up and immediate aftermath, when emotions are the highest. Therefore, an important goal for planners should be to calm clients and limit overreactions.

Literature Review

Hedonic Adaptation

Hedonic adaptation suggests that humans have an innate emotional “set point” and tend to revert to this state shortly after most positive or negative events (Helson 1964; Lyubomirsky 2010). For example, positive emotion from winning the lottery diminishes after a short period (Brickman et al. 1978; Sherman et al. 2020). Emotional reversions from existential stimuli, including the death of a loved one, terminal medical diagnosis, divorce, or job loss (Bonanno 2008) may differ based on personality traits and social engagement (Lucas 2007).

Acute stress interrupts financial decision-making until the individual emotionally regulates to a more normal decision-making state (Porcelli and Delgado 2009). Pinto et al. (2021) showed that in 2012 and 2016, financial well-being suffered when preferred presidential candidates lost. While political and economic perspectives changed, some of the negative views faded after a few short weeks. Hedonic adaptation would suggest that the risk of poor financial decision-making abates as the emotional state regulates.

Affective Forecasting and Emotionally Driven Misestimates

People make affective (emotional) forecasts when predicting how they will feel about future events. Predictions are generally correct in direction but are often incorrect about the degree of emotional reaction (Wilson and Gilbert 2005). People also tend to overestimate the amount of time negative events will be emotionally impactful (Gilbert et al. 1998) and not take into consideration other life events that will affect their emotional state (Wilson et al. 2000). As Wilson and Gilbert (2005) note, “overestimating the impact of negative events creates unnecessary dread and anxiety about the future” (4). The key to stable forecasting may be separating out emotions.

Political Affiliation and Economic Expectations, Stock Market Expectations, and Allocation to Stocks

A growing body of research suggests that political affiliation and the party controlling the presidency impact one’s economic expectations. This has been coined as the “partisan perceptual screen,” where individuals of different parties perceive the world through their political lens (Gerber and Huber 2009). For instance, satisfaction in the democratic process is higher when one’s preferred party wins the election (Anderson and LoTempio 2002; Daoust et al. 2023; VanDusky-Allen and Utych 2021). Individuals are more optimistic and see markets as less risky when their preferred political party has been elected (Bonaparte et al. 2017). They also view economic conditions more optimistically (Bartels 2002). This relationship between political affiliation and economic expectations has increased since the 1980s (Mian 2023).

Literature is mixed regarding whether political affiliation affects implementation rather than merely contemplation. Spending is not based on partisanship (McGrath 2017), and while shifts in economic expectations after the 2008 and 2016 elections were partisan, these shifts did not have any effect on actual household spending (Mian 2023). However, after the 2016 election, Republicans increased stock exposure while Democrats rebalanced to safer assets (Meeuwis et al. 2022). Similar partisan differences in portfolio construction followed the 1992 presidential elections and the 1994 mid-term elections (Bonaparte et al. 2017).

Investors allocate portfolios in conjunction with economic and market expectations. However, when those beliefs change, a statistically insignificant number of individuals tend to make changes (Giglio et al. 2021). Prior research has not studied whether economic and market expectation changes were driven by political conviction after an election and whether these manifested in different actions taken in one’s portfolio. This present research examines the 2020 presidential election and whether politics is uniquely influential in driving emotions and actions.

Financial Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a person’s belief that they have the tools and the ability to drive successful outcomes (Bandura 1977). Financial self-efficacy (FSE) captures elements of self-confidence in financial matters, financial optimism, financial locus of control, and the ability to persevere toward financial goals (Lown 2011). FSE is the “missing link between knowledge and effective action” (Lapp 2010, 1) and can mediate financial knowledge and savings behavior (Rothwell et al. 2016).

Individuals with higher FSE are more likely to invest in the stock market (Qamar et al. 2016; Nadeem et al. 2020), even during times of economic distress (Asebedo et al. 2022). These same individuals are more willing to accept financial risk (Montford and Goldsmith 2016), are less affected by economic and market volatility (Asebedo and Payne 2019; Nadeem et al. 2020), and are better able to adjust to rapid economic change (Engelberg 2007). These stable characteristics signal resilience that may carry over in political seasons. Little research exists to attest whether political changes and political conviction are associated with changes in financial self-efficacy.

Financial Well-Being

Financial well-being (FWB) entails perspectives on financial freedom and security. It is unique to individuals and includes measures such as social and economic environment, personality and attitudes, decision context, knowledge and skills, available opportunities, and behavior (CFPB n.d). FWB has internal and external components (Krijnen et al. 2022) and can change given shifting financial circumstances (Fan and Henager 2022) or the anticipation of change (Barrafrem et al. 2020).

Key differences exist in what drives FWB in politically conservative and liberal individuals (Krijnen et al. 2022). An individual’s perception of FWB depends on trust that the government can deal with financial issues and surprises (Barrafrem et al. 2021). Further, trust in government is a partisan issue, with those politically aligned with leadership exhibiting a higher degree of trust than those who are not (Keele 2005). Lastly, the perception of general well-being is higher when one’s preferred party wins the election (Toshkov and Mazepus 2023).

Research Question and Hypothesis

This study extends the literature on how election results shift economic and market perceptions, financial well-being, and financial self-efficacy. It also evaluates whether individuals made significant changes to their stock portfolios pre- and post-election.

H1: The opposing party winning the election is associated with negative changes to stock market expectations.

H2: The opposing party winning the election is associated with increased pessimism about impending recessions.

H3: The opposing party winning the election is associated with negative changes to financial self-efficacy.

H4: The opposing party winning the election is associated with negative changes to financial well-being.

H5: A reduction in stock allocation is associated with the opposing party winning the election.

H6-H10: Each of these associations will be more pronounced for those with higher levels of political conviction.

Method and Data

Data was gathered as part of an investigation into recipients’ use of economic impact payments in 2020 and 2021. Two waves of surveys were collected, the first in July 2020 and the second in July 2021. The first wave was collected as an open solicitation to U.S. adults. The second wave was collected by reaching out to those who had previously taken the survey. Mechanical Turk (Mturk) was used to recruit the sample. Individuals who participated in the survey had completed at least 500 HITs (Human Intelligence Tasks on Mturk) and had a HIT approval rating of at least 95 percent. These qualifications were chosen to reduce lower quality and bot responses (Peer et al. 2014). The timing of the survey allowed for pre- and post-election observation of political affiliation, economic expectations, financial activities, and financial attitudes. Though the sample is not representative of the U.S. population, it does allow for a more diverse population than most convenience samples (Berinsky et al. 2011; Goodman et al. 2013). While Mturk samples tend to be more liberal and younger than a true representative sample, group comparisons using Mturk samples continue to be an important part of political research (Huff and Tingley 2015). Specific measures of political engagement or action were not measured and may also differ from a representative sample.

The study’s dependent variables measure economic recession and market expectations, financial well-being, financial self-efficacy, and whether an individual made a major change to their stock portfolio since the beginning of the calendar year. Individual expectations of a recession were measured by asking, “How likely do you think that the U.S. economy will experience a recession in the next 12 months?” Participants could answer “not likely at all,” “somewhat likely,” “very likely,” or “not sure.” Not sure was recoded as if the respondents answered somewhat likely. Market expectations were measured by asking, “What is your expectations that the stock market (or indices such as the Dow Jones or S&P 500) will be higher four weeks from now?” with possible responses being “positive,” “negative,” “no change,” or “not sure.” Not sure was recoded as no change. Financial well-being was measured using the five questions from CFPB’s abbreviated financial well-being scale. Scores were transformed by age according to the CFPB’s scoring guide and ranged from 19 to 90.

Stock allocation changes were measured by asking, “How much have you changed your positions in stocks compared to the beginning of the year?” Respondents could answer on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from greatly increased to greatly reduced. To create measures of change in recession, stock expectations, and financial well-being, the 2021 scores were subtracted from the 2020 scores. This resulted in a range of expectations from greatly reduced (i.e., expectations of lower stock market returns) to greatly increased on a five-point scale from −2 to 2. Financial well-being scores were simply the increase or decrease in financial well-being from 2020 to 2021.

The key explanatory variables are party affiliation and political conviction. Survey participants were asked in the July 2020 survey whether they identified as Democrat, Republican, or Independent. Those who answered Democrat or Republican were asked if they identified as strong or not very strong. Independents were asked if they were more similar to Republicans than Democrats, equally similar to both, or more similar to Democrats than Republicans. This was used to create a seven-item scale from very Republican to very Democrat with independent as the middle point. Using this seven-item scale, both party affiliation and the strength of party conviction can be identified.

Objective financial literacy was measured using Lusardi’s financial literacy questions (Lusardi and Mitchell 2011). Subjective financial literacy was measured by asking how strongly a person agrees with the statement, “I have a high level of overall financial knowledge” on a scale of 0 to 11. Financial risk willingness was measured on a scale of 0 to 11 with the question, “How willing are you to take risks in financial matters?” Financial self-efficacy was measured using an eight-item scale with the potential values from each item ranging from 0 to 10, resulting in a range of possible scores from 0 to 80 (Magendans et al. 2017).

Additional demographic measures of age, education, marital status, number of financial dependents, gender, income, net worth, and employment status were included in the model using responses from the second survey. Income, net worth, and employment change measures from 2021 to 2020 were also included to account for socio-economic changes that could reasonably explain outlook and portfolio changes. These change measures were used to reduce the disparate impact economic factors may have had on different political groups and isolate the political effects.

An ordered probit regression with marginal effects was used to analyze stock and recession expectations and changes to stock portfolios, as the dependent variables were ordered categorical variables. Linear regression was used to analyze changes in financial well-being and financial self-efficacy.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

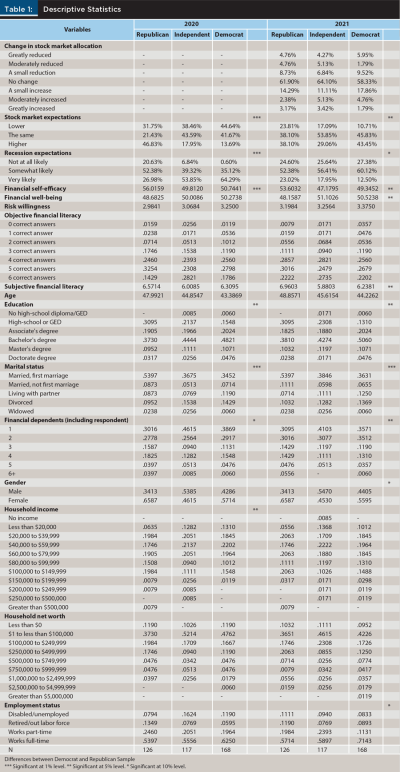

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the 2020 and 2021 surveys. Each year is divided into three groups: Republican, Independent, and Democrat, aggregating the three conviction levels for Republican and Democrat into a singular group for each. T-tests were performed to determine whether there was a significant difference between Republicans and Democrats. Stars indicate if the difference is significant at the 1 percent (***), 5 percent (**), and 10 percent (*) levels.

Republicans (R) and Democrats (D) in this survey differed widely in their expectations of the stock market in 2020. We found 47 percent of Republicans thought the stock market would be higher in four weeks, while only 14 percent of Democrats felt so. In 2021, the two groups were more similar, with 38 percent of Republicans projecting a higher market value and 43 percent of Democrats concurring.

There were also significant differences in expectations of a recession and changes in these expectations. In 2020, 27 percent of Republicans thought a recession would be very likely in the next 12 months, compared to 64 percent of Democrats who felt the same. In 2021, recession expectations for both groups declined to 23 percent for Republicans and 13 percent for Democrats. In this case, the D/R gap changed significantly from positive 37 percent to negative 10 percent. In both years, the difference in economic expectations was statistically significant.

Financial self-efficacy was significantly different for both groups in 2020 and 2021. Republican self-efficacy was higher in both years. However, the D/R gap narrowed slightly from 5.3 in 2020 to 4.3 in 2021. Overall self-efficacy in the sample fell from 2020 to 2021, highlighting the significantly more challenging economic environment all participants felt when the survey was administered in July 2021.

Financial well-being was similar for the two groups, with no statistically significant differences in 2020 and only a moderate difference in 2021. The D/R difference widened slightly from 2020 to 2021, from 1.6 to 2.4. Whether individuals changed their stock portfolio since the beginning of the year was measured solely in 2021. There was no statistically significant difference in changes to stock allocation between Republicans and Democrats.

In both 2020 and 2021, more Republicans were in their first marriage, while more Democrats were single and never married. Republicans also had larger households and higher subjective financial literacy (in 2021), while Democrats had higher levels of education. While the difference between groups of participants in this survey was extensive, there was limited evidence that market and economic expectations were strongly associated with financial well-being, financial self-efficacy, and actual portfolio changes.

Regression Results

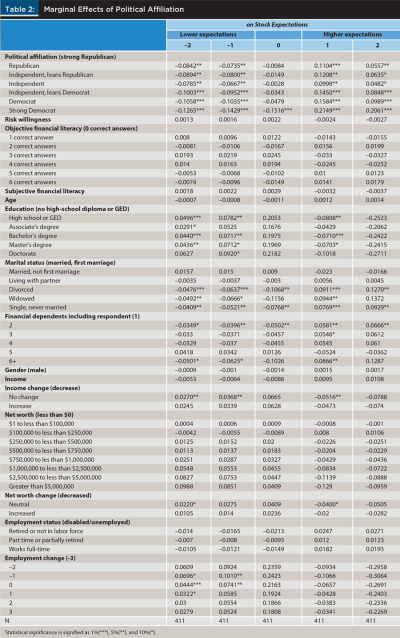

Table 2 shows the marginal effects of political affiliation on changes in stock expectations between 2020 and 2021. Compared to individuals who identify as strong Republicans, all groups had an increased probability of moving from a negative expectation of the stock market to a positive expectation (+1 and +2). In support of hypotheses 1 and 6, individuals who identified as strong Democrats had an increased probability of .21 of more optimistic expectations (+1 and +2) in 2021 than in 2020 compared to strong Republicans.

Compared to individuals with no high school diploma or GED, individuals with a high school degree, bachelor’s degree, or master’s degree had lower probabilities of increased market optimism after the election than before. Stock market expectations increased more for divorced individuals and single, never-married individuals following the election when compared to married individuals in their first marriage. Some individuals with financial dependents were more optimistic about the market compared with individuals with no other financial dependents. Individuals whose income did not change or whose net worth was neutral were more optimistic than those whose income decreased or whose net worth decreased.

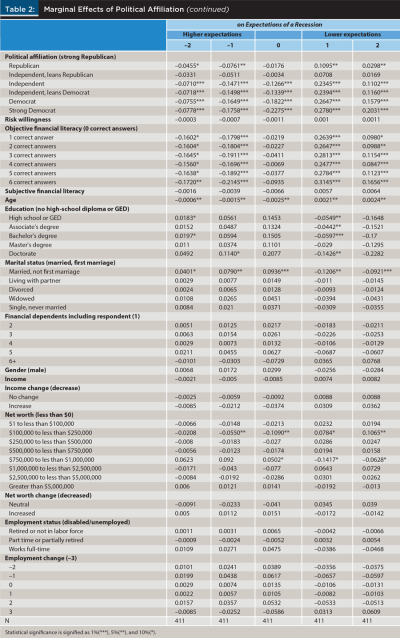

Table 2 also shows the marginal effects of political affiliation on recession expectations. Individuals who thought a recession was less likely are considered more optimistic about the economy. Results are arranged from higher expectations of a recession (pessimistic) to lower expectations of one (optimistic) after the election. Compared to individuals who identify as strongly Republican, all other political affiliations except for “Independent, leans Republican” were more optimistic about avoiding a recession in the next 12 months. In support of hypotheses 2 and 7, strong Democrats had increased probabilities of .28 and .20 of increased expectations of +1 or +2. Independents also had significantly increased optimism with increased probabilities of .23 and .11. To be in the +2 category, an individual must go from believing that a recession was very likely in the next 12 months to believing it was not likely at all. Republicans (compared to strong Republicans) also were more optimistic about the economy, but the marginal effects were smaller at .11 and .03.

Higher objective financial literacy and being older were also positively associated with increased optimism about avoiding a recession. Higher levels of education (compared to no high school diploma) and being remarried (compared to being married, first marriage) were negatively associated with increased economic optimism.

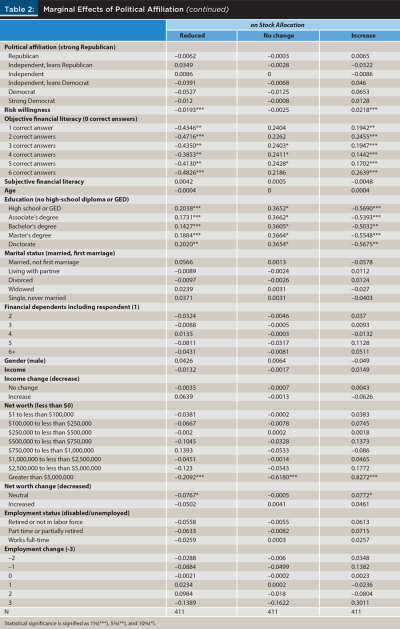

Table 2 also shows the marginal effects of political affiliation on changes in stock allocation between 2020 and 2021. Political affiliation was not associated with changes in stock positions. These results fail to support hypotheses 5 and 10 that political affiliation would be positively associated with making portfolio allocation changes after the election. Higher risk-willingness, objective financial literacy, those whose net worth did not change, and those with a net worth of more than $5 million had an increased probability of reporting an increase in their stock allocations in the 12 months before the second survey. Higher levels of education were associated with reducing stock allocation. However, the consistency of the results for all education groups highlights that only the group with no high school diploma or GED was significantly different from the rest.

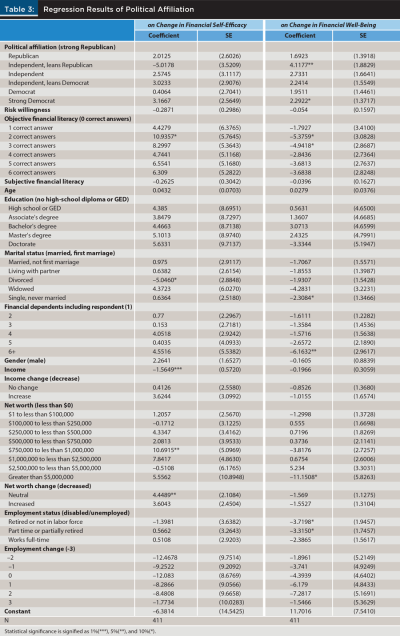

Table 3 shows the regression results of political affiliation on changes in financial self-efficacy from 2020 to 2021. There were no significant findings to support the hypothesis that the election of a preferred candidate would be associated with increased financial self-efficacy. Nor were there findings to support the reverse, that the election of a nonpreferred candidate would be associated with a sense of being unequipped to successfully obtain desired outcomes. These results failed to support hypotheses 3 and 8. Financial self-efficacy changes were marginally and inconsistently significant on a few measures. Being divorced compared to being married (first marriage) was negatively associated with changes in financial self-efficacy, as was higher income. Answering two financial literacy questions correctly was positively associated with changes in financial self-efficacy, as was a net worth of $750,000 to $1 million (compared to negative net worth). Those whose net worth remained consistent also had higher financial self-efficacy changes than those whose net worth fell. Financial self-efficacy remained fairly consistent from 2020 to 2021 despite a variety of changes for study participants. This may relate to the resilience and consistency of the measure.

Table 3 shows the regression results of political affiliation on changes in financial well-being from 2020 to 2021. Two categories of political affiliations had positively significant associations with increased financial well-being: those who were Independent and leaned Republican and those who identified as strong Democrats. Both groups had increased financial well-being (4.12 and 2.29, respectively) compared to strong Republicans. These findings provide limited support for hypotheses 4 and 9.

Correctly answering two or three objective financial literacy questions (compared to 0), being single, never married (married, first time), having six or more financial dependents (1), having more than $5 million in net worth ($0 or less), or those who were retired, working part-time, or partially retired (disabled, unemployed) were each negatively associated with changes in financial well-being. These results were not consistent across the measures (i.e., objective financial literacy at 2 and 3, but not 4, 5, and 6) and were often only marginally significant.

Discussion

Political affiliation was a significant factor in pre- and post-election stock and economic projections. The pronounced disparities in the changes to recession and stock market expectations among supporters of different political parties highlight how connected expectations are to political sympathies. Compared to strong Republicans, strong Democrats exhibited a higher likelihood of shifting their expectations from believing a recession was highly probable to believing it was not probable at all. Additionally, they were more likely to change their outlook on the stock market from anticipating a decline in four weeks to anticipating an increase. While political affiliation was significantly associated with economic and market outlook, the difference was more significant when comparing the extreme ends of the political spectrum. Resetting the reference group (base level) for comparison to Independent, the center measure of the political affiliation scale, the majority of the sample was more similar than different. When the reference group (base level) is changed to Independent, only the strong Republican and strong Democrat groups are statistically significant in their reappraisal of stock market returns in 2021.

Despite political affiliation being connected to visions of the future, we did not find evidence that it was associated with financial self-efficacy. The hypothesis that politically driven economic perceptions would be internalized into a sense of empowerment or powerlessness was not supported. These results point to the resilience and stability of the financial self-efficacy measure and the participants’ consistency in their perception of their ability to effectuate their preferred future despite political changes.

Similarly, political affiliation was not a significant driver of change in financial well-being pre- and post-election. This is contrary to the original hypothesis and can be regarded as a positive finding. While many emotions are expressed about elections, the intensity appears to dissipate with time, and individuals were not significantly affected by the following July. This is consistent with hedonic adaptation, where dramatic short-term emotions dissipate as individuals return to their emotional baseline.

The analysis did not support the hypothesis that political affiliation and the election would be associated with differences in changes to stock allocations. Practitioners may recognize these results reflected in a similar pattern of behavior by clients: short-term emotional statements followed by realizations that the change in administration is probably not reason enough to meaningfully adjust a long-term investment portfolio. Thus, clients decide not to follow through on threats to, for example, “take all of my money out of the stock market until the president is out of office.”

Implications

Findings suggest that while economic and stock market perception shifts around elections vary based on political affiliation, these shifts generally do not result in actual adjustments to one’s stock allocation. Financial planners may not need to proactively address election-related anxiety with every client to keep them in their financial plan. Similarly, given that financial well-being and financial self-efficacy remained stable, specific financial counseling may not be required for most clients. Given the potentially catastrophic impact of emotionally driven changes, planners need to be ready to address more political clients and those who appear most distressed.

Despite limited actions taken in response to elections, this project still leaves financial professionals with tangible takeaways to share with clients. Conversations between advisers and clients regarding election-related impacts on their portfolios and financial plans are a regular and natural part of the client–planner relationship. Sharing that most individuals do not make significant changes in their stock allocation and that financial self-efficacy and financial well-being remain (or will eventually become) stable following an election may help clients stay calm. The adage “don’t just do something, sit there” is likely to be the right choice when it comes to decisions about how to respond to scary events (whether they be market volatility or changes in presidential power). This paper provides evidence to support the idea that people tend to do this in practice. Explaining these findings to clients may result in a reduction in election-induced anxiety.

For clients with strong political beliefs who are considering taking action, there are several best practices to consider. An adviser can help their client uncover how they would advise someone else who may be facing a similar decision. Studies show individuals are often more pragmatic and less emotional when giving others advice for the same situation than they would give themselves (Arriaga and Rusbult 1998; Grossmann and Kross 2014). One such “other” could be the client’s “future self.” Emotions can cause individuals to be short-sighted and not consider the long-term consequences of decisions. People treat their future selves as strangers for whom the ramifications of decisions need not be considered (Burum et al. 2016). Advisers can ask their client to write a letter to their future self to strengthen the connection between the present and future. This action reduces poor decision-making by having the client consider a longer time horizon (Gelder et al. 2013). Another option is for the adviser to create and periodically revisit the client’s investment policy statement (or even a risk tolerance assessment with results that both the client and adviser accept). Agreed-upon investment plans can provide stability when times feel uncertain.

Advisers can help clients remember that even if their political party loses, most aspects of their day-to-day life will likely see minimal or no change. Indeed, even from a market perspective, returns have generally been positive in election years and over time (Santa-Clara and Valkanov 2003). People overpredict how long they will react emotionally to events, but this could be reduced by “asking people to think about other future events that are likely to occupy their thoughts” (Wilson et al. 2000, 833). Encourage anxious clients to imagine a normal day in their life following the election to help remind them that most aspects of life are going to remain the same.

Limitations

Participants in the study were surveyed four months prior to the election in survey period 1, and approximately nine months post-election in survey period 2. Future studies could vary these lengths to get more near-term and long-term measurements and better understand how projections change over time. Another challenge was that the measurements were taken during a unique financial and social period. The first survey was taken soon after the market crash in 2020 while the country was still in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and although the second survey was delivered during less turbulent times, it came shortly after economic stimulus was distributed. Although the study controlled for demographic variables when analyzing Republican versus Democrat sentiment, political events alter the political climate in the United States and are almost certainly felt differently by each party. Events that transpired between the two surveys (e.g., specific COVID spikes, political demonstrations) cannot be replicated, resulting in unique circumstances that make some of the representativeness of our results uncertain.

The sample itself was not balanced to be representative of the U.S. population. Future surveys could ensure better balance, including geographical, to ensure less biasing of data as some states were over-represented and were affected differently by COVID-19 and responses to it. A replication of this survey in different environments and with a representative sample would provide rigidity to these findings.

Conclusion

Consistent with previous research, elections influence economic expectations. However, elections seem to have significantly less influence on financial well-being and self-efficacy. While in our study, too few individuals shifted their portfolios in response to the election to be statistically significant, planners do and will have clients who need assurances to help them stick to their financial plan.

A major element that differentiates this study from others cited is that this survey was distributed well after the election when emotions were significantly different than the immediate aftermath of the election. This is the primary hypothesis that needs future investigation. It is possible that data gathered immediately after the 2020 election might have shown that political affiliation was associated with differences in financial well-being, financial self-efficacy, and portfolio changes. Indeed, this is when planners are the most engaged with their clients on these issues.

Planners can work with clients to visualize their future, consider day-to-day life, and remember that market returns have no consistent pattern in response to elections. By empowering individuals with specific steps and actions aimed at building resiliency and self-efficacy, planners can equip individuals to be in a position of control over their finances. This will aid in future challenges that they face.

Citation

Gray, Blake, Thomas Crandall, and Donovan Sanchez. 2025. “Dealing with the Aftermath: Understanding Political Sympathy’s Association with Financial Perspectives, Wellness, Efficacy, and Portfolio Actions and How to Help Clients After Major Events.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (5): 58–78.

References

Anderson, Christopher J., and Andrew J. LoTempio. 2002. “Winning, Losing and Political Trust in America.” British Journal of Political Science 32 (2): 335–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123402000133.

Arriaga, Ximena B., and Caryl E. Rusbult. 1998. “Standing in My Partner’s Shoes: Partner Perspective Taking and Reactions to Accommodative Dilemmas.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 24 (9): 927–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167298249002.

Asebedo, Sarah D., Taufiq Hasan Quadria, Blake T. Gray, and Yi Liu. 2022. “The Psychology of COVID-19 Economic Impact Payment Use.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 43 (2): 239–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09804-1.

Asebedo, Sarah, and Patrick Payne. 2019. “Market Volatility and Financial Satisfaction: The Role of Financial Self-Efficacy.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 20 (1): 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2018.1434655.

Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Barrafrem, Kinga, Daniel Västfjäll, and Gustav Tinghög. 2020. “Financial Well-Being, COVID-19, and the Financial Better-than-Average-Effect.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 28 (December): 100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100410.

Barrafrem, Kinga, Gustav Tinghög, and Daniel Västfjäll. 2021. “Trust in the Government Increases Financial Well-Being and General Well-Being during COVID-19.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 31 (September): 100514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100514.

Bartels, Larry M. 2002. “Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions.” Political Behavior 24 (2): 117–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021226224601.

Berinsky, Adam, Gregory Huber, and Gabriel Lenz. 2011. “Using Mechanical Turk as a Subject Recruitment Tool for Experimental Research.” Submitted for Review, November 7, 2011.

Bonanno, George A. 2008. “Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive after Extremely Aversive Events?” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy S (1): 101–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.101.

Bonaparte, Yosef, Alok Kumar, and Jeremy K. Page. 2017. “Political Climate, Optimism, and Investment Decisions.” Journal of Financial Markets 34 (June): 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmar.2017.05.002.

Brickman, Philip, Dan Coates, and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman. 1978. “Lottery Winners and Accident Victims: Is Happiness Relative?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36 (8): 917–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.917.

Burum, Bethany A., Daniel T. Gilbert, and Timothy D. Wilson. 2016. “Becoming Stranger: When Future Selves Join the Out-Group.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 145 (9): 1132–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000193.

CFPB. “Financial Well-Being: What It Means and How to Help.” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Accessed October 16, 2023. www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/financial-well-being/.

Daoust, Jean-François, Carolina Plescia, and André Blais. 2023. “Are People More Satisfied with Democracy When They Feel They Won the Election? No.” Political Studies Review 21 (1): 162–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299211058390.

Engelberg, Elisabeth. 2007. “The Perception of Self-Efficacy in Coping with Economic Risks among Young Adults: An Application of Psychological Theory and Research.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (1): 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00494.x.

Evans, Geoffrey, and Robert Andersen. 2006, February. “The Political Conditioning of Economic Perceptions.” The Journal of Politics 68 (1): 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00380.x.

Fan, Lu, and Robin Henager. 2022. “A Structural Determinants Framework for Financial Well-Being.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 43 (2): 415–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09798-w.

Gelder, Jean-Louis van, Hal E. Hershfield, and Loran F. Nordgren. 2013. “Vividness of the Future Self Predicts Delinquency.” Psychological Science 24 (6): 974–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612465197.

Gerber, Alan S., and Gregory A. Huber. 2009, August. “Partisanship and Economic Behavior: Do Partisan Differences in Economic Forecasts Predict Real Economic Behavior?” American Political Science Review 103 (3): 407–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990098.

Giglio, Stefano, Matteo Maggiori, Johannes Stroebel, and Stephen Utkus. 2021. “Five Facts about Beliefs and Portfolios.” American Economic Review 111 (5): 1481–1522. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200243.

Gilbert, Daniel T., Elizabeth C. Pinel, Timothy D. Wilson, Stephen J. Blumberg, and Thalia P. Wheatley. 1998. “Immune Neglect: A Source of Durability Bias in Affective Forecasting.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 (3): 617–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.617.

Goodman, Joseph K., Cynthia E. Cryder, and Amar Cheema. 2013. “Data Collection in a Flat World: The Strengths and Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26 (3): 213–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1753.

Grossmann, Igor, and Ethan Kross. 2014. “Exploring Solomon’s Paradox: Self-Distancing Eliminates the Self-Other Asymmetry in Wise Reasoning About Close Relationships in Younger and Older Adults.” Psychological Science 25 (8): 1571–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614535400.

Helson, Harry. 1964. “Current Trends and Issues in Adaptation-Level Theory.” American Psychologist 19 (1): 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040013.

Huff, Connor, and Dustin Tingley. 2015. “‘Who Are These People?’ Evaluating the Demographic Characteristics and Political Preferences of MTurk Survey Respondents.” Research & Politics 2 (3): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015604648.

Jackson, Jeremy. 2019, June. “Happy Partisans and Extreme Political Views: The Impact of National versus Local Representation on Well-Being.” European Journal of Political Economy 58: 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.12.002.

Keele, Luke. 2005. “The Authorities Really Do Matter: Party Control and Trust in Government.” The Journal of Politics 67 (3): 873–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00343.x.

Krijnen, Job, Gülden Ülkümen, Jonathan Bogard, and Craig Fox. 2022. “Lay Theories of Financial Well-Being Predict Political and Policy Message Preferences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 122 (2): 310–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000392.

Lapp, William M. 2010. “The Missing Link: Financial Self-Efficacy’s Critical Role in Financial Capability.” EARN White Paper. San Francisco, CA.

Lown, Jean M. 2011. “Development and Validation of a Financial Self-Efficacy Scale.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22 (2): 54–63. www.researchgate.net/publication/228293306_Development_and_Validation_of_a_Financial_Self-Efficacy_Scale.

Lucas, Richard E. 2007. “Adaptation and the Set-Point Model of Subjective Well-Being: Does Happiness Change After Major Life Events?” Current Directions in Psychological Science 16 (2): 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00479.x.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17078.

Lyubomirsky, Sonja. 2010. “Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences.” In Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0011.

Magendans, J., Jan M. Gutteling, and Sven Zebel. 2017. “Psychological Determinants of Financial Buffer Saving: The Influence of Financial Risk Tolerance and Regulatory Focus.” Journal of Risk Research 20 (8): 1076–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1147491.

Majumder, Maimuna S., Colleen M. Nguyen, Linda Sacco, Kush Mahan, and John S. Brownstein. 2017, September 12. “Risk Factors Associated with Election-Related Stress and Anxiety Before and After the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/u4hns.

McGrath, Mary C. 2017. “Economic Behavior and the Partisan Perceptual Screen.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 11 (4): 363–83. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00015100.

Meeuwis, Maarten, Jonathan A. Parker, Antoinette Schoar, and Duncan Simester. 2022. “Belief Disagreement and Portfolio Choice.” The Journal of Finance 77 (6): 3191–3247. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13179.

Mian, Atif, Amir Sufi, and Nasim Khoshkhou. 2023, May 9. “Partisan Bias, Economic Expectations, and Household Spending.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 105 (3): 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01056.

Montford, William, and Ronald E. Goldsmith. 2016. “How Gender and Financial Self-Efficacy Influence Investment Risk Taking.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 40 (1): 101–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12219.

Nadeem, Muhammad Asif, Muhammad Ali Jibran Qamar, Mian Sajid Nazir, Israr Ahmad, Anton Timoshin, and Khurram Shehzad. 2020. “How Investors Attitudes Shape Stock Market Participation in the Presence of Financial Self-Efficacy.” Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553351.

Peer, Eyal, Joachim Vosgerau, and Alessandro Acquisti. 2014. “Reputation as a Sufficient Condition for Data Quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk.” Behavior Research Methods 46: 1023–31. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0434-y.

Pinto, Sergio, Panka Bencsik, Tuugi Chuluun, and Carol Graham. 2021. “Presidential Elections, Divided Politics, and Happiness in the USA.” Economica 88 (349): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12349.

Pitcho-Prelorentzos, Shani, Krzysztof Kaniasty, Yaira Hamama-Raz, et al. 2018, August. “Factors Associated with Post-Election Psychological Distress: The Case of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Psychiatry Research 266: 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.008.

Porcelli, Anthony J., and Mauricio R. Delgado. “Acute Stress Modulates Risk Taking in Financial Decision Making.” Psychological Science 20 (3): 278-283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02288.x.

Qamar, Muhammad Ali Jibran, Muhammad Asif Nadeem Khemta, and Hassan Jamil. 2016. “How Knowledge and Financial Self-Efficacy Moderate the Relationship between Money Attitudes and Personal Financial Management Behavior.” European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences 5 (2): 296–308. https://european-science.com/eojnss/article/view/3234.

Rothwell, David, Mohammad Nuruzzaman Khan, and Katrina Cherney. 2016. “Building Financial Knowledge Is Not Enough: Financial Self-Efficacy as a Mediator in the Financial Capability of Low-Income Families.” Journal of Community Practice 24 (4): 368–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2016.1233162.

Santa-Clara, Pedro, and Rossen Valkanov. 2003.“The Presidential Puzzle: Political Cycles and the Stock Market.” The Journal of Finance 58 (5): 1841–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3648176.

Sherman, Arie, Tal Shavit, and Guy Barokas. “A Dynamic Model on Happiness and Exogenous Wealth Shock: The Case of Lottery Winners.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (1): 117–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00079-w.

Smith, Kevin, Aaron Weinschenk, and Costas Panagopoulos. 2023, March 15. “On Pins and Needles: Anxiety, Politics and the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 34 (3): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2023.2189258.

Toshkov, Dimiter, and Honorata Mazepus. 2023. “Does the Election Winner–Loser Gap Extend to Subjective Health and Well-Being?” Political Studies Review 21 (4): 783–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299221124735.

VanDusky-Allen, Julie, and Stephen M. Utych. 2021. “The Effect of Partisan Representation at Different Levels of Government on Satisfaction with Democracy in the United States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 21 (4): 403–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2021.2.

Wilson, Timothy D., and Daniel T. Gilbert. 2005. “Affective Forecasting: Knowing What to Want.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14 (3): 131–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00355.x.

Wilson, Timothy D., Thalia Wheatley, Jonathan M. Meyers, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Danny Axsom. 2000. “Focalism: A Source of Durability Bias in Affective Forecasting.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78 (5): 821–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.821.