Journal of Financial Planning: May 2024

Chris Heye, Ph.D., is founder and CEO of Whealthcare Planning and Whealthcare Solutions.

I have previously characterized financial wellness as a hierarchical pyramid,1 analogous to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.2 In this conceptualization, the financial wellness pyramid comprises five levels (starting from the bottom of the pyramid): organizational wellness, physical wellness, cognitive wellness, behavioral wellness, and holistic wellness. My characterization of financial wellness is broader and more holistic than definitions that focus mostly on activities and decisions that occur at the bottom of the pyramid at the “organizational wellness” level.

But financial wellness is a process, not a static state, and the concept of financial wellness as a hierarchical pyramid should not mask the dynamic nature of achieving wellness. There is a distinctive time element to attaining holistic wellness, that is, in “moving up” the various stages of the pyramid. Moreover, for most people, achieving wellness is a non-linear process. Certain stages of the pyramid may be more easily reached than others, and some people may get “stuck” in one or more levels as they seek to ascend the hierarchy.

The dynamic nature of realizing holistic financial wellness is driven in large measure by the aging process. Different stages of wellness are easier to reach and sustain at different times in people’s lives. For example, many older adults have successfully achieved organizational and physical wellness, but struggle with cognitive and/or behavioral wellness. Many younger adults, on the other hand, take a long time to attain organizational wellness, but can quickly achieve physical and cognitive wellness.

But how exactly does aging shape the dynamics of achieving holistic wellness?

There are at least three causal mechanisms associated with aging that influence a person’s ability to reach and maintain each stage of the pyramid. Of course, every person is different, and the process of moving up the hierarchy will be unique to each of us. But the journey of financial wellness over time will be shaped in some way by at least one, if not all three, of these factors.

Health and Financial Wellness

The most obvious way aging affects our financial wellness is via changes in our health status. Older adults are not as healthy as younger ones. Approximately 80 percent of adults over the age of 55 suffer from at least one chronic illness, like diabetes, asthma, or cancer. By age 65, that figure rises to roughly 86 percent.3 About 18 percent of children aged 0–11 years, 27 percent of young adults aged 12–19, 46.7 percent of adults between age 20 and 59, and 85 percent of adults age 60+ used prescription drugs in the previous 30 days.4 The average 65+ year old adult takes four medications, and 39 percent take five or more.5

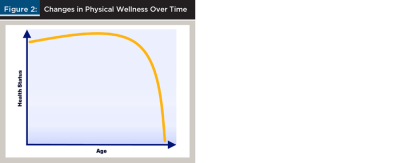

In short, achieving and maintaining “physical wellness” becomes more difficult over time. A stylized interpretation of the health-related risks to our financial wellness looks something like Figure 2.

For most of us, the risks to our physical wellness are low early in life, but then gradually increase over time as the status of our health declines. The physical wellness journey is often very non-linear. Many people experience excellent health for many years, and then a single event, like the diagnosis of cancer or a heart attack, can set off a chain reaction of health-related challenges and financial threats that can last the rest of their lives.

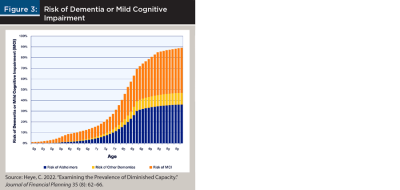

Aging also has a strong influence on a person’s ability to achieve and maintain cognitive and behavioral wellness. In a previous article, I estimated the likelihood of a person having dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at any age.6 I have reproduced the summary chart in Figure 3.

Not surprisingly, there is a strong (non-linear) correlation between aging and the likelihood of experiencing cognitive decline. The overall dynamic looks similar to the trend depicted in Figure 2. Most of us have few or no cognitive issues prior to about age 70. But then the probability of declining cognitive wellness increases rapidly. Because dementia patients can also experience symptoms such as heightened emotions, impulsivity, anxiety, and anger, behavioral wellness can also be much more difficult to achieve in our later years.

Life Transitions

The ability to successfully manage important life transitions—a move to a new location, the birth of a child, a marriage—is critical to our emotional and physical well-being. It is also crucial to our ability to achieve and maintain financial wellness.

For most of us, our adolescence and early years of adulthood are characterized by frequent life transitions. We make new friends, attend new schools, go off to college, start our career, and perhaps get married and have a child. If you have (or had) young children, you know how much time you need to spend helping them adapt to the many changes that occur early in life. Managing and mentoring children and young adults through these transitions in many ways is the key to successful parenting.

But then, for many of us during the middle decades of our lives, things tend to settle down. We become more established in our careers, figure out how to parent our kids, deepen our personal relationships, and become more comfortable with who we are and what we are doing. Because we are not constantly needing to respond to short-term challenges in our lives, it is easier for us to focus on the longer term and the bigger picture. Many people will have accumulated sufficient financial resources by this time that they can afford to obtain advice from financial, legal, and healthcare professionals, making all facets of financial wellness easier to achieve.

Later in life, however, we are again confronted with the need to manage major transitions. Most people want to retire, or at least work a lot less, once they reach their mid-60s. The retirement transition can be quite challenging, especially for men. In recent years, divorce rates have skyrocketed for adults in their 50s and 60s, resulting in massive transitions for older couples and their families. Health events, including the death of a spouse or parent, can initiate major adjustments, including the need to move to a more age-friendly living situation, and dramatically change a person’s lifestyle, dreams, and goals.

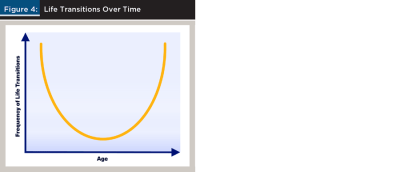

A stylized representation of the consequences of life transitions for financial wellness is shown in Figure 4. It depicts a U-shaped curve where the frequency of transitions is highest earlier in life, and then again in our later years. Transitions later in life pose a direct threat to financial wellness, e.g., adjusting to lower income levels following retirement, death of spouse, or divorce. Moreover, the need to manage transitions later in life can be a major source of stress, anxiety, and depression. Financial professionals working with older clients should be especially attentive to possible threats to financial wellness during these transitional life events.

Learning

The third way that aging impacts our financial wellness is via the learning process. As we get older, we learn how to manage our personal finance and healthcare needs more effectively, make better decisions about our health, and improve our lifestyle choices. This process is often referred to as “crystalized” learning or intelligence. As people age, they accumulate a larger mental database of information and skills, which in turn can be used to solve problems and make important decisions.

This capacity to acquire and store knowledge has positive impacts on our financial wellness. Many young adults have difficulty achieving even the most basic aspects of financial wellness because they lack an understanding of financial concepts, products, and risks. As a result, they make sub-optimal financial decisions that can jeopardize both short- and long-term financial security. Younger adults may similarly make poor or risky choices about their health and lifestyles because they lack the accumulated knowledge that supports sound decision-making.

But financial literacy tends to increase with age; so too a person’s understanding of the healthcare and legal systems, the risks associated with poor lifestyle choices, and importance of maintaining good health. There is also strong evidence that emotional intelligence, which involves understanding and managing emotions and impulses, continues to develop and improve with age and experience. So, for most of us, learning has a positive impact on our reasoning powers and personal choices as we age. Over time, knowledge gaps get filled in, impulses are checked, and financial wellness improves.

Up to a point. A major study has concluded that “peak” financial reasoning occurs at age 53.7 Other studies have found that for many adults, financial literacy starts to decline after age 50.8 Dementia and other health issues can have significant impacts on our ability to learn new concepts and facts, as well as our capacity to remember old ones.

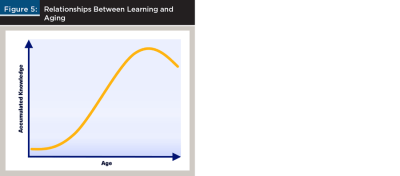

A stylized presentation of the relationship between learning and aging is shown in Figure 5. Most of us move quickly up the learning curve during middle age, but then at some point learning stops and may even go into reverse.

The backside of the learning curve can have incredibly damaging consequences for financial decision-making, and hence financial wellness. Many people reach peak wealth at the same time they experience a permanent decline in their capacity to make sound financial decisions. This can be a dangerous period if their decisions are not closely monitored. Even the best laid financial plans can be torpedoed overnight by a few unsound or impulsive decisions.

Final Thoughts

The dynamic nature of financial wellness has important consequences for the services and advice provided by financial professionals. Younger clients will require more coaching through life events and need more help with basic financial literacy and education. Most middle-aged clients will require fewer major course corrections but will need assistance preparing for health- and longevity-related risks that jeopardize their long-term financial and retirement security. For older clients, much of the focus needs to be on helping them through major life transitions and monitoring and managing signs of cognitive decline.

In short, financial wellness is a journey, not a destination. Recognizing and meeting the wellness requirements of different clients at different stages of their lives is critical to successful financial planning.

Endnotes

- Heye, C. 2020. “Introducing a Hierarchy of Financial Wellness.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (9): 38–41.

- Maslow, A.H. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50 (4): 370–96.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). n.d. “Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over with Chronic Conditions.” 2008 National Health Interview Survey. www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm.

- Martin, Crescent B., Craig M. Hales, Qiuping Gu, and Cynthia L. Ogden. 2019, May. “Prescription Drug Use in the United States, 2015–2016.” NCHS Data Brief No. 334.

- Sollitto, Marlo. n.d. “Polypharmacy in the Elderly: Taking Too Many Medications Can Be Risky.” AgingCare. www.agingcare.com/articles/polypharmacy-dangerous-drug-interactions-119947.htm.

- Heye, C. 2022. “Examining the Prevalence of Diminished Capacity.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (8): 62–66.

- Agarwal, S., J.C. Driscoll, X. Gabaix, and D. Laibson. 2009. “The Age of Reason. Financial Decisions over the Life-Cycle with Implications for Regulation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2009 Fall: 51–101.

- Finke MS, J.S. Howe, and S.J. Huston. 2017, January. “Old Age and the Decline in Financial Literacy.” Management Science 63 (1): 213–230.