Journal of Financial Planning: June 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- The research underscores the importance of making academic findings more relevant and actionable for financial planners, moving beyond theoretical debates to foster direct, actionable takeaways for practitioners.

- Results indicate that while many financial planners report regularly engaging with academic research, there remains a substantial subset that finds it difficult to understand or apply these insights. Dense language, paywalls, and demanding schedules can be barriers to adviser engagement with academic research.

- Findings highlight a desire for changes in research dissemination, providing summaries, and using more engaging formats (e.g., podcasts, short videos). Such formats align with planners’ time constraints and could bolster regular research use in day-to-day client work.

- Financial planners are encouraged to actively voice their needs and preferences regarding research and build relationships with academics to proactively shape the future of research in financial planning. Likewise, academics are invited to provide implications that are clearly explained, jargon-free, and readily applicable to planning contexts.

- By broadening dissemination channels and ensuring research is both rigorous and accessible, the profession can capitalize on evidence-based approaches that enhance client outcomes, elevate professional standards, and advance the field of financial planning as a whole.

Khurram Naveed, a CFA charterholder and CFP® professional, holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics, a Master of Arts in Economics, and an M.B.A. from the University of Missouri-St. Louis. He is currently a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University.

Donovan Sanchez, CFP®, is a personal financial planning instructor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a senior financial planner with Model Wealth, Inc., and a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an associate professor in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. Dr. McCoy volunteers for the Financial Therapy Association Board of Directors and serves as the co-editor of the Financial Planning Review.

Blake Gray, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. Dr. Gray is a part of the Powercat Financial education initiative.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

Advancing the financial planning profession should be at the heart of academic research (Buie and Yeske 2011). To that end, research should be usable beyond conversations at conferences or in classroom environments. Relatedly, financial planning practitioners should incorporate research-driven best practices so that they are providing clients with the best service possible. Rules of thumb may be useful, but unless and until they are tested, assumptions used by planners may ultimately prove suboptimal or erroneous (Sampson 2024). For practitioners to incorporate research into their practice, however, they must read and understand it.

For this to happen, and to help the profession continue to mature and develop, planners and academics will need to strengthen their professional relationships and seek to better communicate with one another. To that end, researchers and doctoral students at Kansas State University undertook a survey of financial planning practitioners to better understand where they go to find information related to their practice, and to understand the perspective of how effective researchers are at transmitting their findings to planner audiences.

Findings from this project highlight where practitioners obtain information and how often they read research. Additionally, survey respondents shared changes they would like to see in how research is disseminated. This undertaking affirms the importance of conducting practical and relevant research and highlights that findings should be delivered in a way that promotes understanding, is free of jargon and specialized language, and recognizes the sensitive time constraints associated with being a practitioner. Results from this study suggest that there are meaningful ways for researchers to improve how findings are delivered. The research team hopes that journals, financial planning organizations, universities, researchers, and practitioners will work toward finding ways to disseminate research in a manner that will reach the intended audience and be utilized in practice and policy.

Literature Review

In financial planning, a gap exists between the research academics produce and the research practitioners prefer (Sanchez et al. 2025). This divide is driven in part by the distinct cultures in which researchers and practitioners operate, each with divergent priorities, goals, and communication styles (Fothergill 2000). The idea of distinct and separate domains between research and practice is sometimes referred to as the two-communities theory (Caplan 1979). The theory highlights that the more academics distance themselves from the day-to-day challenges of practitioners, the more their research tends to become niche and disconnected from real-world applications (Newman et al. 2016). As an example, researchers may value rigor (reliability and validity of their studies) over practical relevance, narrowing their focus in ways that unintentionally hinder the application of their findings in real-world situations where complex and diverse factors not included in their research come into play. While practitioners prioritize actionable, immediate solutions to address clients’ needs, these solutions may be more difficult to test for trustworthiness and may lack empirical validation as the complexities and diversity of client experiences are hard to test in research.

Implementing academic research within a professional setting can be particularly daunting when studies are conducted in environments (survey or artificial environments) or using terminologies unfamiliar to practitioners (Van de Ven 2018). Practitioners’ reluctance to engage with academic research is often due to its perceived irrelevance and apparent lack of respect for practical implications (Levine 2020). This suggests a need for researchers to align their studies more closely with the real-world challenges faced by professionals. The use of academic jargon and complex language in research further exacerbates this divide, making it challenging for practitioners to access and apply findings in their daily work. The Pew Research Center, for example, found that while research scientists are generally regarded as intelligent and capable of solving complex problems, they are not often seen as effective communicators (Funk et al. 2019).

Institutional incentives also play a role in widening the research–practice gap. Academic institutions emphasize peer-reviewed publications as the primary means of knowledge dissemination, which, while valuable for scholarly purposes, are often less accessible to practitioners because of journal paywalls (Day et al. 2020). The reward systems in academia, including tenure and promotion, do not incentivize researchers to engage with practitioners or disseminate findings in a format that is readily usable in practice (Pendell and Kimball 2021). For their part, financial planning practitioners frequently face heavy client workloads, time constraints, and limited resources, restricting their ability to engage with academic literature and research. Furthermore, weak communication channels contribute to the lack of collaboration between the two groups (Fothergill 2000).

There is a notable absence of intermediaries or “knowledge brokers” who can translate academic research into applications for practitioners (Fothergill 2000). While conferences and professional associations present potential opportunities for interaction, they may be underutilized or inaccessible due to logistic or financial barriers. Additionally, both researchers and practitioners have limited opportunities for sustained interpersonal interaction, which could foster mutual understanding and encourage the integration of academic insights into practice (Sanchez et al. 2025). The gap between research and practice highlights the need for innovative dissemination strategies that address the financial planners’ practical needs and enhance research usability in real-world settings.

Method

The survey included questions about the frequency and utility of academic research, preferred research journals, primary sources of information, and desired changes in research dissemination. It aimed to capture how often respondents read academic research, how useful they found it, which journals they read, and where they obtained information. These questions provided detailed insights into the engagement of financial planners with academic research. An open-ended question invited suggestions for improving research dissemination. Demographic data, including age, gender, education, years of experience, certifications, role, firm type, and fee structure were also collected to understand the diversity of respondents and their practice settings.

Participants

This research was carried out in partnership with the Financial Planning Association. For a more thorough discussion of the research methodology, please see Sanchez et al. (2025). The survey was distributed to Financial Planning Association members through direct email and various social media outlets (i.e., LinkedIn and Facebook). Two-hundred-ninety responses were initially received, but not every participant responded to each question. The responses to the questions that we focused on in this study varied from 108 to 172 due to missing data. A detailed breakdown of the sample characteristics is provided in Table 1. It is important to note that some participants may hold more than one certification, so the counts for these demographics are provided as total counts.

To gain insight into the preferences and feedback of financial planners regarding research dissemination, respondents were asked five questions designed to capture detailed information on various aspects of their engagement with academic research and to identify key areas for improvement in how research is shared and utilized. The first four questions were structured with specific answer choices, allowing respondents to select predefined options, which aimed to capture the frequency of research consumption, preferred sources of research, and the types of research they found most useful.

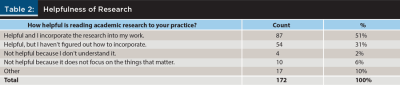

The survey began by exploring how useful respondents found academic research in their practice. The first question asked, “How helpful is reading academic research to your practice?” with options for (1) Helpful, and I incorporate the research into my work; (2) Helpful, but I haven’t figured out how to incorporate; (3) Not helpful because I don’t understand it; (4) Not helpful because it does not focus on things that matter; and (5) Other. This first question aimed to understand the practical value of academic research for financial planners.

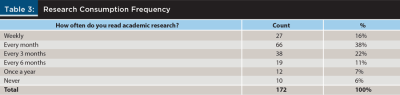

Transitioning to the frequency of engagement, the second question focused on how often respondents read academic research, with options for (1) weekly, (2) every month, (3) every three months, (4) every six months, (5) once a year, and (6) never. This question provided insights into the regularity with which financial planners engage with academic literature, indicating their level of consumption of research findings.

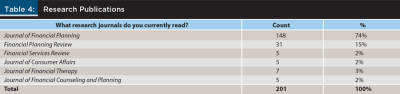

The next question was about specific sources of academic research, asking, “What research journals do you currently read?” Respondents selected among the following answer choices: (1) Journal of Financial Planning, (2) Financial Planning Review, (3) Financial Services Review, (4) Journal of Consumer Affairs, (5) Journal of Financial Therapy, (6) Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, and (7) Other. This third question helped to identify the most frequently read publications among financial planners.

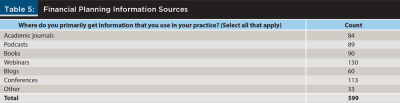

To further understand the sources of information the practitioners use, the fourth question asked, “Where do you primarily get information that you use in your practice?” Respondents were then invited to select among the following answers: (1) Academic Journals, (2) Podcasts, (3) Books, (4) Webinars, (5) Blogs, (6) Conferences, and (7) Other. This question focused on the channels through which financial planners stay informed and updated, highlighting the importance of different media formats in their professional development.

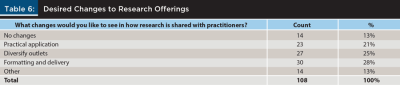

The final question was open-ended, asking, “What changes would you like to see in how research is shared with practitioners?” Using thematic analysis, we classified these open-ended responses into several categories based on recurring themes and suggestions (Braun and Clarke 2006). Two authors on the paper first identified the recurring themes and subsequently placed each response into its respective theme. Later, all authors reviewed this classification and made final adjustments using a consensus approach. This classification allowed the identification of key areas for enhancing the dissemination and practical application of research within the financial planning community, thereby providing actionable insights for researchers.

Results

Structured questions capture quantitative data, whereas open-ended questions offer qualitative insights. The question, “How helpful is reading academic research to your practice?” revealed that most respondents (51 percent) found academic research helpful and incorporated it into their work. Another 31 percent found it helpful but difficult to incorporate. These findings specify interest in academic research and highlight barriers to practical application. A small portion (2 percent) found the research unhelpful because they did not understand it, while 6 percent felt it did not focus on relevant matters.

The frequency of reading academic research also varied among respondents. About 16 percent read academic research weekly, 38 percent monthly, and 22 percent every three months. For survey participants engaging with research on a less frequent basis, 11 percent read it every six months, 7 percent once a year, and 6 percent never. While many respondents engage regularly with research, almost a quarter (24 percent) of respondents read it twice a year or less.

When asked about research journals currently read, the Journal of Financial Planning was the most frequently cited with 148 respondents indicating they read this journal. This is expected, given that the survey was disseminated through the Financial Planning Association. This was followed by Financial Planning Review (31), Financial Services Review (5), Journal of Consumer Affairs (5), Journal of Financial Therapy (7), and Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (5). Fourteen respondents answered this question by providing a range of sources that did not fit into predefined journal categories. These include “Kitces” (3), Financial Advisor Magazine (2), NAPFA Advisor Magazine (2), other trade magazines or websites (4), and news or email (2). One respondent named four nonfinancial planning journals that they currently read (Journal of Political Economy, Econometrica, Journal of Experimental Psychology, Demography).

Respondents were also asked about the primary sources of information they use in practice. Webinars were the most popular with 130 selections, followed by conferences (113), books (90), podcasts (89), academic journals (84), blogs (60), and other sources (33). This suggests a preference for diverse forms of learning and information consumption. It may also highlight an appetite for sources that are easier to integrate into a busy professional schedule compared with reading traditional academic journals.

The final question, “What changes would you like to see in how research is shared with practitioners?” provided a range of responses: A total of 21 percent suggested practical applications within research, 25 percent requested diversification of research outlets, 28 percent emphasized formatting and delivery improvements, 13 percent said no changes were necessary, and 14 percent had other miscellaneous suggestions. These responses highlighted specific areas for improvement in research dissemination, emphasizing the need for practical application, diverse dissemination channels, and clear communication.

Discussion

Research remains crucial to financial planning and for the great majority of practitioners. However, a good portion struggle incorporating research into their practice. While slightly more than half of survey participants read research monthly, very few journals are used, and most survey respondents get their information from webinars, conferences, podcasts, or other sources. To improve access and use, practitioners want clear and practical applications as well as changes to the format and delivery of research through more channels.

To understand how well research shares practical applications, a recent decade-long review of the Journal of Financial Planning assessed the extent to which authors explicitly articulated implications for practitioners (Anderson et al. 2022). This review analyzed 257 articles and found they all included clear implications with 90 having a distinct section dedicated to practical implications. The Journal of Financial Planning may be uniquely focused on practical implications compared to other journals. Reviews from the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (Goyal and Kumar 2023), Financial Services Review (Hanna et al. 2011), and Journal of Consumer Affairs (Baker, Kumar, and Pandey 2021) did not address whether they included implications or applications, especially applications for financial planners. The review of the Journal of Family Economic Issues (Dolan 2020) did not review the articles for their presence or not, but it highlighted the need for practical implications that could be drawn from future research in key areas, such as the unique experiences of diverse racial and ethnic families, financial and economic well-being, work-family conflict, and family businesses. Future journal reviews could be more intentional about incorporating a focus on the key implications for practice found in the articles they review. In addition, journals can work toward encouraging a separate implication section to be a requirement for publication.

Research can take two possible approaches: either give guidance on what should happen in an ideal environment or describe what is likely to happen in different environments (Hanna et al. 2011). Describing what should happen is broadly informative as readers often look for guidance and practical applications to benefit their practice and create environments for success. While academics publish and are rewarded for both types of work, distinctive goals often result in a misalignment between academics and practitioners (Ingstrup, Bruun, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Adlin 2021). Research that focuses on what should happen may be missing the mark by being too disconnected for what is actually happening or is achievable in real-world settings. This is evidenced by survey respondents requesting more practical application, examples, and case studies. Many research journals on the other hand see little value in such efforts, creating more separate communities.

Practitioners are actively consuming research and implementing improvements in their practices. While many appear to find it useful, planners also provide clear and consistent messaging on the challenges they find with research. One challenge mentioned is that academic language is unique. It has been said that learning to read research is like learning a second language. If this is true, then we (academics) have created an intense barrier to research. In practice, rigor, academic language, and statistical methods are regularly prioritized in research over clarity, application, and usefulness. This is not to say that academics should simplify their research. Rather, academics need to both maintain rigor and focus on writing clear and precise implications and findings. Practical application and clearer writing could make research less difficult to incorporate.

Survey participants also call for diversifying methods of delivery. An academic journal’s impact and influence on the profession can be limited in scope as it only captures a particular segment of the industry. The changing media landscape exerts further pressure to positively adapt to new opportunities that didn’t exist a few decades ago. Participants in this survey call for more methods of delivery because many other sources of information and entertainment have already begun providing content across multiple channels. This presents a challenge and an opportunity. While it may be new from the academic side, it is not new to practitioners or other end-users. Creating multiple paths to consuming research can aid in making research more accessible and increase the frequency of use.

Limitations

Survey participants were recruited primarily through the Financial Planning Association and, therefore, are not representative of all financial service professionals. It is not surprising that the Journal of Financial Planning (complimentary to members of the Financial Planning Association) was the most-read journal. Academic journals behind paywalls have been a consistent barrier between academics and practitioners (Day et al. 2020), so it is worth noting that this limitation may provide support for reducing paywalls for journals.

Another possible bias from the recruiting process may be that those most interested in research are more likely to respond to a survey about research. In this way, results about how often research is read and how important respondents feel it is may be overstated compared to a more generalized population. In addition to marketing through the Financial Planning Association, the authors shared the survey link through social media. Respondents, in this way, are also more likely to be associated with researchers and academics and are also more likely to have favorable views of research.

Survey respondents were also concentrated in terms of where they worked. The majority of survey respondents worked as registered investment advisers (RIA). In 2020, however, less than one-fifth of all advisers worked at RIAs (Cerulli Associates 2021). This discrepancy may be a result of the response options available to choose from for the question, “What industry type is your firm?” and because the primary source of distribution was through FPA, which primarily serves RIA advisers. Respondents were asked to select between working for a wirehouse, broker–dealer, RIA, trust company, or other. They were not able to select more than one option. In 2020, however, more than half (51.6 percent) of FPA members were dually registered and the majority were RIA (Financial Planning Association 2020). Future iterations of this survey will benefit from giving participants a dual registration option to select from and by broadening communication through additional organizations to capture more broker–dealer advisers. Five participants selected “other” and typed in “hybrid” or “BD/RIA.” The current sample is more closely matched to readers of FPA’s Journal of Financial Planning and therefore more closely tied to the experiences of its readers than perhaps more broker–dealers. Beyond those limitations to generalizability, not all responses were complete and usable.

Conclusion and Practical Implications

Findings from this project highlight how often practitioners interact with research, where they obtain their information, and what practitioners would like to see change to build more synergy among planners, academics, and other interested parties. There are actionable steps forward for practitioners and academics to consider as all work to improve dissemination of research to practitioner audiences.

Practitioners are encouraged to continue making their voices heard by researchers. To date, formal surveys of practitioners to understand how they want research presented to them, as well as requests to understand what changes should be made, are relatively rare. Practitioners are invited to engage as participants in future survey opportunities, but they are also invited to meet, email, and connect with academics to discuss their views. Relatedly, practitioners should consider how they might strengthen and grow their circle of academic connections. Academic and practitioner echo chambers should be avoided, and cross community collaboration championed.

Practitioners bring significant value to relationships with academics by providing them with practical insights and emerging trends from their experiences. They can serve as advisers and collaborate on research by helping to align study design and outcomes with a practical real-world perspective. Feedback can improve clarity of research ensuring language is clear to financial planning audiences. Conferences are an especially good time to forge these connections as they serve as an open forum to observe, present, question, and provide insight and ideas for future research. These discussions should help research align more closely with current trends and financial planners’ areas of interest.

Building connections with academics does not need to be cordoned off to formal events, however. Academics’ emails are readily available on university websites and modern technology makes meetings and discussions relatively easy. Practitioners can also connect with academic research by looking at topics of interest by browsing Google Scholar and other scholarly websites. For example, if a planner is interested in learning about retirement income strategies, financial therapy interventions, or tax optimization techniques, searching Google Scholar for those keywords is a great start. It is also possible to look at a specific researcher’s profile on Google Scholar to see their list of publications and better understand their scope of expertise and focus.

Academics must maintain the rigor, use of scientific methods, and statistical techniques to ensure results and implications are sound and broadly applicable. While it is not practical for financial planning research to be entirely jargon-free or void of statistical methods, academics need to address the difficulty of understanding their writing. Proofreading of articles by professionals and other non-academics can bring insight into what parts are unclear and can help clarify and improve writing. Planners might also consider using tools like AI writing tools (e.g., Grammarly, Wordtune) to summarize research in different styles and complexity (though care should be used to be certain the AI is interpreting findings accurately). Many tools will offer suggestions of how to state the same thing with different audiences in mind (academic, professional, etc.).

Academics sometime produce journal articles that sit behind paywalls separated from the non-academic population. Yet, academics have freedom to create videos, podcasts, websites, email lists, LinkedIn summaries, and a whole host of other resources to discuss theirs and other research in digestible portions. By repacking formal financial planning research (that has already gone through the peer review process to ensure accuracy) in ways that make them accessible to planners, academics have the opportunity to better serve both financial planners and clients through better outcomes. They also have the opportunity to differentiate themselves in the new marketplace.

At the heart of great research are good, clear, and meaningful questions answered using the best scientific measures that provide trustworthy results. Academics and practitioners both have very important roles to play in creating a system and synergistic culture that promotes such activity. While pracademics (practicing academics) play an important role in having a foot in both camps, we also need the very best of both to find common ground and get to work identifying and solving complex problems. The opportunity to create something unique in this profession will require overlapping communities that give and take the best from each other to create trustworthy and meaningful research for both academic and professional use.

Citation

Naveed, Khurram, Donovan Sanchez, Megan McCoy, and Blake Gray. 2025. “Strengthening Adviser–Academic Connections: Making Financial Planning Research Accessible and Actionable.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (6): 60–71.

References

Anderson, Jason, Ashlyn Rollins-Koons, Stephen Azaloff, Ruth McCaleb, Cheryl Rauh, and Megan McCoy. 2022. “A Decade of Research in the Journal of Financial Planning (2011–2021).” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (9): 70–81. www.financialplanningassociation.org/learning/publications/journal/SEP22-decade-research-journal-financial-planning-2011-2021.

Baker, H. Kent, Satish Kumar, and Nitesh Pandey. 2021. “Five Decades of the Journal of Consumer Affairs: A Bibliometric Analysis.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 55 (1): 293–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12347.

Bartunek, Jean Marie, and Sara Lynn Rynes. 2014. “Academics and Practitioners are Alike and Unlike: The Paradoxes of Academic–Practitioner Relationships.” Journal of Management 40 (5): 1181–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314529160.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011. “Evidence-Based Financial Planning: To Learn ... Like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 38–43. www.onefpa.org/business-success/newtotheprofession/Documents/Contributions_Buie.pdf.

Caplan, Nathan. 1979. “The Two-Communities Theory and Knowledge Utilization.” American Behavioral Scientist 22 (3): 459–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427902200308.

Cerulli Associates. 2021. U.S. Advisor Metrics 2021: Client Acquisition in the Digital Age.

Day, Suzanne, Stuart Rennie, Danyang Luo, and Joseph D. Tucker. 2020. “Open to the Public: Paywalls and the Public Rationale for Open Access Medical Research Publishing.” Research Involvement and Engagement 6: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-0182-y.

Dolan, Elizabeth M. 2020. “Ten Years of Research in the Journal of Family Economic Issues: Thoughts on Future Directions.” Journal of Family Economic Issues 41 (4): 591–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09737-1.

Financial Planning Association. 2020. Membership Dashboard: October 2020.

Fothergill, Alice. 2000. “Knowledge Transfer between Researchers and Practitioners.” Natural Hazards Review 1 (2): 91–8. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2000)1:2(91).

Funk, Cary, Meg Hefferon, Brian Kennedy, and Courtney Johnson. 2019. “Trust and Mistrust in Americans’ Views of Scientific Experts.” Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/08/02/trust-and-mistrust-in-americans-views-of-scientific-experts/.

Goyal, Kirti, and Satish Kumar. 2023. “A Bibliometric Review of Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning between 1990 and 2022.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 34 (2): 138–68. https://doi.org/10.1891/JFCP-2023-0009.

Hanna, Sherman D., HoJun Ji, Jonghee Lee, et al. 2011. “Content Analysis of Financial Services Review.” Financial Services Review 20 (3): 237–51. www.researchgate.net/publication/279964029_Content_analysis_of_Financial_Services_Review.

Ingstrup, Mads Bruun, Leena Aarikka-Stenroos, and Nillo Adlin. 2021. “When Institutional Logics Meet: Alignment and Misalignment in Collaboration Between Academia and Practitioners.” Industrial Marketing Management 92: 267–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.01.004.

Levine, Adam Seth. 2020. “Why Do Practitioners Want to Connect with Researchers? Evidence from a Field Experiment.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53 (4): 712–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000840.

Newman, Joshua, Adrian Cherney, and Brian W. Head. 2016. “Do Policy Makers Use Academic Research? Reexamining the ‘Two Communities’ Theory of Research Utilization.” Public Administration Review 76 (1): 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12464.

Pendell, Kimberly, and Ericka Kimball. 2021. “Dissemination of Applied Research to the Field: Attitudes and Practices of Faculty Authors in Social Work.” Insights 34 (1). https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.546.

Sampson, Carla Jackie. 2024. “Minding the Gap in Evidence-Based Practice.” Frontiers of Health Services Management 40 (4): 1–4.

Sanchez, Donovan, Megan McCoy, Khurram Naveed, and Blake Gray. 2025. “Bridging the Adviser-Academic Gap: A Call to Unite Practitioner Preferences with Academic Research.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (4): 60–75

Van de Ven, Andrew H. 2018. “Academic-Practitioner Engaged Scholarship.” Information and Organization 28 (1): 37–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.02.002.