Journal of Financial Planning: June 2025

By Peter Tiboris, CFP®, CEO and Partner, Park Avenue Capital; Chris Bremer, Chief Investment Officer, Park Avenue Capital; and Fred Ulbrick, Lead Research Analyst, Park Avenue Capital.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the image below for a PDF version.

Warren Buffett, one of the most disciplined investors in modern history, has famously said he gets about a quarter of his daily calories from Coca-Cola, Cherry Coke in particular. He has joked about eating like a kid, with a diet that includes burgers, ice cream, and soda, while maintaining a rigorous investment approach.

Such dietary habits might make a nutritionist shudder, but the deeper truth is, we are all drawn to things that look shiny, taste good, or feel novel—even if we know they might not serve us well in the long run.

Enter direct indexing—the industry’s latest attempt to repackage passive exposure with a sweetener that comes with a premium price tag.

The ETF Revolution and the Active Management Fallout

Over the last two decades, the investment landscape has undergone a fundamental shift, moving away from traditional actively managed mutual funds toward lower-cost, index-based, exchange traded funds.

These novel instruments, developed in the early 2000s, came with the diversification benefits of mutual funds with intraday liquidity and a more advantageous tax structure. Today, ETFs have become the default investment vehicle for millions of investors.

ETFs addressed many pain points that plagued the post-2000 technology bubble environment—high investment costs, tax inefficiency, and a growing body of evidence exposing the significant underperformance of active managers. ETFs offer a compelling answer to these challenges.

The ETF evolution was more than a new medium for investment—it was a significant disruption. And like any disrupted industry, the legacy players have been trying to rebuild what they lost.

The Revenue Problem for Traditional Asset Managers

There are three key revenue challenges confronting active management investment firms.

First, there is an ongoing max exodus to low-cost investment products. According to Bloomberg, over $2.7 trillion has flowed out of equity mutual funds since 2012, while $4.4 trillion has flowed into equity ETFs (exchange traded funds). According to Morningstar, the average asset-weighted expense ratio for active U.S. equity funds in 2023 was 0.60 percent, and the average-weighted expense ratio for passive funds was 0.11 percent. That translates to an estimated $16.4 billion in lost revenue for the mutual fund complex since 2012, redistributing revenue centers to low-cost behemoths like Vanguard or Blackrock. A pivot to novel solutions from industry players has been necessary for survival.

Second, over that same period, the total asset flows into fixed income are 1.8 times greater than equities. While the average fee for actively managed bond funds is slightly less than equity funds, 60 percent of fixed income flows are going to low-cost ETFs, thus exacerbating the revenue challenge.

Third, new investors, including those partnering with advisers, are increasingly defaulting to low-cost ETF preferences. Not only are actively managed fund sponsors losing clients, they also are not acquiring new investors. Before the advent of ETFs, actively managed funds were the default position; now these fund companies must work even harder to convert investors away from a low-cost starting position. As Buffett would say, active management is not an industry with an inherent competitive advantage.

Viewed through the revenue challenge lens, direct indexing, and any sponsor-developed “innovation,” should be viewed with a high degree of skepticism.

Direct Indexing: A Solution in Search of a Problem

Direct indexing is only one of many products marketed as innovation to meet mostly imaginary needs, such as customization, flexibility, “buffered” solutions that purport to hedge downside, “enhanced” yield (that mostly means higher tax cost), and access to “private” markets. The trend has gained significant momentum. According to Fidelity’s 2024 RIA Benchmarking Study, 50 percent of registered investment advisers (RIAs) with assets exceeding $1 billion are currently offering or planning to offer direct indexing to clients.

Direct indexing strategies are similar to index-based products in that they look to track the performance of an index but do so by owning a sample of the individual securities in the index compared to a single mutual fund or ETF ticker. Given the ownership of individual securities, direct indexing solutions are often marketed to customize index level exposure. For example, when ESG (environmental, social, and governance) was a hot trend in the investment space, direct index sponsors promoted the ability for investors to express preferences at the security level.

The irony is that direct indexing starts from an acknowledgment that indexing has won the game, but the more an investor customizes, the greater the migration away from the index and toward an actively managed approach. Now that the ESG marketing campaign has lost momentum, direct index sponsors have moved to the next shiny object—tax alpha.

The Tax Alpha Mirage

The biggest argument we see out there today is the use of direct indexing SMAs (separately managed accounts) for tax-loss harvesting. Direct index sponsors promote tax alpha, but most quantitative research is based on hypotheticals, a considerable red flag. There are three critical issues direct indexing promoted for tax benefits: additions in perpetuity, tax loss decay, and hocus pocus marketing.

1. Additions in perpetuity. Most promises of ongoing tax efficiency in SMAs require consistent additions to the portfolio over time, because in the absence of new cash, gains in securities reach a level where losses are no longer available during market volatility. Markets are up two of every three years, so direct indexing sponsors acknowledge the tax loss opportunity is front loaded when no future cash is added to the strategy.

Further, if a client is contributing regularly to the portfolio, they don’t need to own hundreds of stocks to realize tax alpha. ETFs on their own are sufficient to generate tax losses during market volatility because a client will have unique lots with cost basis for each ETF purchase.

2. Tax loss decay. Once the direct indexing strategy loses the ability to harvest losses, the client owns a portfolio of individual stocks that has three critical problems:

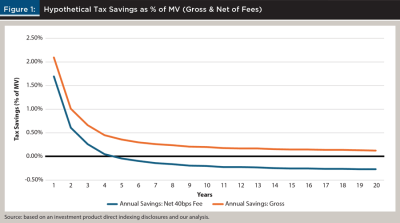

a. Cost drag: Stocks are trapped by gains in the SMA, which is many times the cost of the representative index. If the client did nothing from that point forward, the fee difference alone would consume the tax alpha well within 10 years.

b. Tracking error and tax friction: The composition of the underlying index changes over time—companies come and go and index weights evolve. Do you keep holding all the individual stocks even though they may not be the best representation of the underlying index you are looking to track? Clients that want to avoid tracking error will need to rebalance, causing taxes the strategy was designed to avoid.

c. Behavioral trap of complexity: Over time the investor becomes locked into a complex web of individual stock movements, tax complications, and behavioral inertia. What happens in 10 or 20 years when the product sponsor shutters the offering, or the investor simply chooses a simpler path? Now the investor, or their adviser, is stuck with managing a portfolio of three hundred or more individual securities, each with a gain/loss profile and tax implications. The logistical and psychological burden impacts decision making, and investors get stuck owning the next generation of GE, Cisco, and IBM, not out of conviction, but out of paralysis.

3. Hocus pocus marketing. We find most of the tax benefit analysis in the direct indexing disclosures to be insincere.

a. Tax alpha is calculated using the highest available federal income tax bracket. Most clients in portfolio distribution mode are focused on generating long-term, not short-term capital gains. This sleight of hand significantly overstates alpha (and thus returns) and is an incredibly deceptive marketing ploy.

b. We have also seen additional disclosure language that overstates return projections of the strategy in a different way: “The team also calculates a ‘tax benefit,’ which assumes the tax savings remain invested in the market and compound over time.” This methodology is flawed and misleading. Tax carry forwards can be a footnote on the investor’s personal balance sheet but should not be considered reinvested and compounded in the projected returns of the strategy.

For these reasons, direct indexing fails to fulfill its promises and is clearly a way for sponsors to trap clients in expensive SMAs.

Other Considerations

Practical areas that are often missed or overlooked in a direct indexing sales pitch:

Tax reporting complexity. Instead of a simple 1099 form, clients receive pages of transaction details, making overall tax assessment and preparation more cumbersome.

Wash sale complications. Direct indexing has the potential for wash sales across other strategies, especially other SMAs, that are used throughout an investor’s portfolio. A wash sale occurs when an investor sells a security at a loss and repurchases the same or “substantially identical” security within 30 days. With direct indexing’s numerous positions, this rule becomes difficult to monitor across multiple strategies and accounts, potentially negating some intended tax benefits.

Increased time. Implementing any investment strategy that promises alpha necessitates extra time, research, and energy in explaining or justifying the investment selection to the client. This is a significant distraction from the ultimate goals of implementing an asset allocation designed for the client’s specific planning objectives.

Practical Alternatives for Advisers

To the extent that direct indexing is used to implement a long-term investment strategy consistent with the client’s financial goals, we believe that an adviser is delivering value in planning and asset allocation alignment. However, using direct indexing as the implementation solution for that client is more sizzle than substance.

Advisers need to approach the investment sponsor community with a very skeptical eye. The industry has been completely transformed given the dominance of passive strategies over the last decade, and reliable revenue centers have been decimated. The burden of proof to veer from passive tools that offer low costs, diversification, liquidity, and simplicity should be exceptionally high. We find that, ironically, leading with a simple investment framework is the path of most resistance because it’s not newsworthy or interesting cocktail party conversation. However, in the end, it creates far more sustainable portfolio outcomes that lead to enduring client relationships.