Journal of Financial Planning: January 2024

Dr. Michael Kothakota co-owns WolfBridge Wealth and has 18 years of experience in financial planning. His research interests include behavior and artificial intelligence. He teaches financial planning at Columbia University. He earned his M.S. in predictive analytics from Northwestern University and his Ph.D. in financial planning from Kansas State University.

Dr. Jessica Wery co-owns WolfBridge Wealth. Her research interests include behavior and motivation. She is an experienced educator and has taught at North Carolina State University, University of North Carolina, and Elon University. She earned her Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction from North Carolina State University.

Note: Click the images below for a PDF version

Personal financial planning practitioners often struggle to use the results of financial planning research, including behavioral finance research. Many studies using large existing data sets that yield general information that is useful in describing population characteristics can be difficult to translate into actions financial planners can employ with their clients (Bogan, Gezcy, and Grable 2020). By their very design, those larger scale studies aggregate data to yield outcomes so that it can be generalized to the wider population. This process may obscure individual nuances. As such, many planners report frustration or dissatisfaction with this research, citing the incongruency with the individualized nature of the practice of financial planning. Here, we describe an approach that practicing financial planners (as well as researchers) can use to evaluate practices and interventions that respond to the individual characteristics of clients.

Overview of Single-Case Research as a Data-Based Decision-Making Approach

Single-case research designs have been used in applied behavioral research for over a century. They are not only scientifically rigorous (Kratchowill and Levin 2015), but also sound and efficient methods for practicing financial planners to use a data-based decision-making process that can inform their practice and measure their impact.

Unlike large-scale research that often compares one group to another (e.g., treatment to control group), single-case research employs a within-individual or within-group analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention or practice. Single-case research has informed the practical fields of behavior, education, psychology, and, more recently, exercise science (Kazdin 1989; Kratchowill and Levin 2015; Page and Thelwill 2013). This type of applied research is ideal for testing the effectiveness of interventions designed to change behavior in individualized professional settings such as financial planning. Financial planning by its very nature is individualized to meet each client’s unique needs, values, goals, and strengths. Planners know no two clients are the same.

Single-case research designs are both efficient and easy to implement by practitioners within their work with clients. The process provides valuable, objective, and data-based insights. For financial planners, this process may start with a client’s need. Planners may have a client who is exhibiting behaviors that are inconsistent with their stated goals or needs and wonder if a particular intervention would help. The next step includes identifying the behavioral outcome (i.e., how one would know if that intervention were effective) and deciding how to measure it. In addition, clearly describing and measuring the implementation of that intervention is essential to making a reliable evaluation. After obtaining buy-in and consent of the client, the practitioner can implement the intervention and collect the outcome data. These data are evaluated throughout the process and used to make decisions about proceeding.

The single case research method includes several designs. Here we will use one such design, the changing criterion design, to illustrate this process. We will share a hypothetical situation in which a financial planner wants to evaluate the effectiveness of a goal-setting strategy on increasing a client’s savings rate.

Behavioral Finance in Personal Financial Planning

The practice of financial planning has drawn on behavioral finance research to provide an understanding of the psychological and emotional factors that influence an individuals’ financial decision-making. For example, behavioral finance acknowledges people are not always rational. Clients come to financial planners with cognitive biases and emotional responses, such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and herding behavior, which can lead to suboptimal financial choices. Financial planners often act as behavioral coaches, helping clients stay disciplined during market fluctuations and avoid common biases that can lead to irrational decision-making, and encouraging clients to focus on their financial goals and stay committed to their investment strategies, even when short-term market events induce anxiety.

Additionally, behavioral finance research has provided an understanding of how individuals perceive and frame their financial goals. Planners are encouraged to communicate effectively with clients by framing financial objectives in ways that resonate with their emotions and motivations, providing emotional support and reassurance during periods of financial stress.

Increasing Savings Rate Behavior

In the case of savings behavior, the field of financial planning posits rules of thumb about how much an individual or household should save for various goals (Sabat and Gallagher 2019). However, financial planners know their clients experience a tension between savings and consumption. Life cycle hypothesis (Ando and Modigliani 1956) or behavioral life cycle hypothesis (Sheffrin and Thaler 1988) describe this behavior. However, these are descriptive models, and few financial planners find them helpful in motivating change in client behavior.

Employer-sponsored plans (e.g., 401(k), 403(b)) have implemented behavioral finance approaches but are critiqued as being paternalistic (Thaler and Sunstein 2021). In this approach, participants must “opt out” of saving, and some even include built-in increases in automatic savings (Benartzi and Thaler 2013). However, this approach has also been critiqued for affecting an individual’s agency and failing to provide sufficient financial education during new employee onboarding (Cable, Gino, and Staats 2013). Also, this approach does not consider the individual’s current consumption and shorter-term goals. While this solution may be effective for the masses within a given macro view, it may not be the best solution for a specific individual. What is the solution?

The following hypothetical situation illustrates how a financial planner could design and evaluate an intervention based on a client’s specific characteristics and needs. We illustrate use of a changing criterion design as a data-based decision-making process to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention that increases a client’s savings rate.

The Situation

Deirdre is a financial planner who has several clients who have begun saving but are not saving at a rate that helps them reach their stated long-term goals. She has decided to implement a changing criterion goal-setting intervention with one of her clients, Barry.

Prior to working with Deirdre, Barry was not saving consistently. Deirdre used a technique known as framing (Todd 2019), in which the planner utilizes a positive, story-driven scenario visualizing the outcome of achieving a goal to encourage clients to begin saving. After implementing this intervention, Barry has been consistently saving 1 percent of his income while meeting other financial obligations. However, Barry’s savings rate of 1 percent per month is far below the savings rate of 4.5 percent Deirdre has projected Barry needs to meet his goals. A review of financial statements confirms Barry has been saving at a rate of 1 percent for the last six months. Barry understands that he needs to save more yet has not been able to increase his savings rate. Barry stated he needs to wait until he receives a raise. Deirdre explained that his raises are built into the projections, and the 4.5 percent assumes future increases.

The Intervention

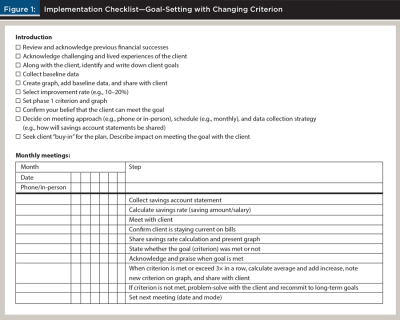

Using what she knows about Barry, Deirdre understood that shifting from a 1 percent to 4.5 percent (a 450 percent change) savings rate would be difficult for Barry. In fact, he has stated that doing so “feels impossible.” However, Deirdre has read in the behavioral research that a 10–20 percent change in behavior feels more attainable, so she decided to try a 10 percent increase. Deirdre also knows Barry is more effective when his successes are acknowledged and when he knows he will be accountable to reporting back to her on a regular basis, so she decided to set monthly phone check-ins with quarterly in-person meetings. During these meetings, Barry will share his progress, solve problems if necessary, and together they will plot his savings rate on a graph. As “savings rate” was the behavior of interest, Dierdre decided to use Barry’s savings account statement to measure his savings rate, and verbal confirmation from Barry to measure that he is staying current with his bills. Consistent with behavioral research, Deirdre set a pace for increasing the goal to three consecutive months of meeting or exceeding the goal. With this information in mind, Deirdre wrote a short but detailed description of his intervention and created her own implementation checklist (See Figure 1).

Her intervention included several key components: (1) acknowledged Barry’s background and history of saving, (2) obtained Barry’s buy-in and consent, (3) set realistic and attainable goals, (4) graphed outcome data, and (5) conducted regular meetings to summarize Barry’s performance.

Dierdre used this checklist to hold herself accountable for delivering the intervention as she intended over time and to be able to share it with others who are interesting in replicating her work.

Following the Changing Criterion Goal-Setting Implementation Fidelity Checklist she created, Deirdre met with Barry in July 2020 and sought his buy-in and consent to proceed. In that meeting she showed Barry his baseline data, confirmed his long-term goals, and shared her belief that he was capable of meeting those goals.

The Hypothesis

Setting an attainable increasing savings rate goal with Barry, meeting monthly, and graphing savings rate outcomes will increase his savings rate toward a level that meets his stated goals.

Research Design

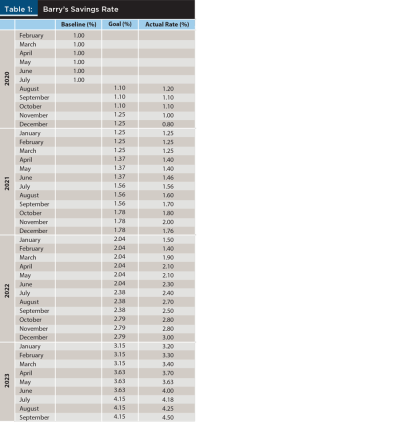

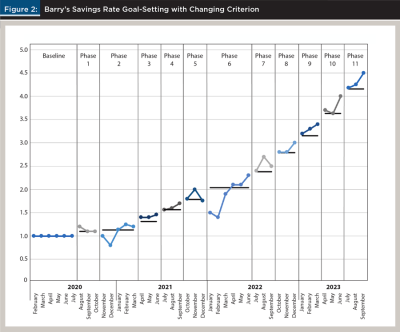

Dierdre selected the changing criterion design, which leverages successive increases in the behavioral outcome over time. Table 1 and Figure 2 describe Barry’s monthly goals and savings rates. Before the intervention (baseline), Barry’s savings rate was consistently 1 percent (February through July 2020). An initial 10 percent increase was added to Barry’s baseline savings rate of 1 percent. As such, the goal (i.e., criterion) for phase 1 is 1.1 percent of his salary. Barry’s goal is represented on the graph (Figure 2) by the black horizontal line in each phase. Also note the data points are connected within each phase, but not across phases. Additionally, a vertical line separates each phase.

Results

In the first phase of the intervention, Barry was able to save 1.2 percent, 1.1 percent, and 1.1 percent, which met or exceeded his initial goal of 1.1 percent. As such, 1.2 percent, 1.1 percent, and 1.1 percent were averaged and a 10 percent increase was added (1.133 percent × 10 percent = 1.247 percent). Barry’s goal for the second phase is now 1.247 percent. During monthly calls with Barry, Deidre acknowledged and celebrated his successes.

In phase 2, Barry was unable to meet his goal in November and December 2020. In their monthly calls, Barry reported expenses associated with the holidays impacted his ability to save at his goal rate. After this, Barry recommitted to saving to meet his future goals. Within this process, Deirdre can discuss roadblocks and solve problems with Barry as needed and respond to the real-life events of her client. Life is not an optimization problem and can be messy.

After the holiday retrenchment, Barry met his goal in January 2021 and exceeded his goal in February and March of that year. Consistent with the plan, they implemented a 10 percent increase from Barry’s three months of meeting or exceeding the previous goal. Barry’s goal for phase 3 is 1.374 percent. He met that criterion in the following three months. This process continued successfully until phase 6 when Barry again struggled to meet his expenses for the winter holidays and meet his goal.

At this point, Deirdre and Barry came up with a plan to prepare for future holiday spending (e.g., winter holiday savings plan distributed across the year, and developing and committing to sticking to the holiday budget). The winter holidays occurred in Phase 8, and Barry was able to meet his savings goal over that period. Figure 2 illustrates Barry’s savings rate outcome and shows a change in the behavior from 1 percent to 4.5 percent in September 2023.

Conclusion

In its simplest form, the scientific method is carefully manipulating a variable and measuring its impact on another variable. Scientific rigor comes from ensuring both the intervention and the observations are accurately observed and measured. Robust data-based decision-making uses the same guiding principles. In this case, we illustrated how a goal-setting intervention (i.e., independent variable) used within changing criterion design affected a client’s saving rate outcome (i.e., dependent or outcome variable). The savings account statement, a type of permanent product recording, is a reliable, objective measure of the desired behavior, the savings rate. Diedre’s implementation fidelity checklist measuring the intervention implementation allows for others to replicate this process and provides evidence for internal validity. The graphed data was visually analyzed along the way, and modifications to the intervention were set in place as needed.

Within this hypothetical example, Deirdre was able to respond to the idiosyncratic characteristics of her client, design an intervention that aimed to help her client meet his goal, objectively measured the client’s behavioral outcome, consistently monitored her implementation of the intervention, and analyzed the outcome data presented in a graph. In doing so, she was also able to identify and respond to Barry’s need for holiday spending and that impact on his savings rate. The graphing of the data not only supported Barry’s progress but also provided a mechanism to observe the impact of holiday spending. As she observed the effectiveness of this intervention, Deirdre decided to implement similar interventions with four other clients.

This approach provides an illustration of a powerful use of behavioral finance combined with a robust data-based decision-making process and evaluate specific financial planning services. Financial planners can mirror Deirdre’s approach with Barry or adapt it to meet the specific needs of their clients —keeping financial planning personal.

Single-case research allows practitioners and researchers to test the effectiveness of an intervention with one or more clients. Not to be confused with case studies, single-case research methods are scientifically rigorous. This scientific rigor is the result of the careful application of the scientific method, ensuring that research is credible, reliable, and reproducible. At its core, it involves drafting a research question and formulating hypotheses, selecting an appropriate research method, objectively and accurately collecting outcome data, analyzing that data, and deriving conclusions that are strictly contingent upon the data. Additional scrutiny through peer review and replication by independent researchers adds to the reliability of the results and serves as a bulwark against inadvertent errors or deliberate malfeasance, solidifying the credibility and generalizability of scientific knowledge.

While we illustrate how this objective approach can be used by financial planners with an intervention designed to help this client increase his saving behavior, the same approach can be used with any intervention that is aimed at changing a behavior that is difficult to change (i.e., behaviors in which large changes are difficult but smaller incremental changes are attainable). It can be used by practitioners to test, modify, and evaluate financial planning practices/interventions and determine if and how effective those practices are with their real clients. Furthermore, this process provides data that is immediately actionable by financial planners. It can also be used by researchers as a means to evaluate the effectiveness of financial planning practices and close the “research-to-practice gap.”

References

Ando, A., and F. Modigliani. 1963. “The ‘Life Cycle’ Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and Tests.” The American Economic Review 53 (1): 55–84.

Benartzi, S., and R. H. Thaler. 2013. “Behavioral Economics and the Retirement Savings Crisis.” Science 339 (6124): 1152–1153.

Bogan, V. L., C. C. Geczy, and J. E. Grable. 2020. “Financial Planning: A Research Agenda for the Next Decade.” Financial Planning Review 3 (2): e1094.

Cable, D. M., F. Gino, and B. R. Staats. 2013. “Reinventing Employee Onboarding.” MIT Sloan Management Review.

Kothakota, M. G., & Kiss, D. E. (2020). “Use of Visualization Tools to Improve Financial Knowledge: An Experimental Approach.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 19 (2).

Kratochwill, T. R., and J. R. Levin (Editors). 2015. Single-case Research Design and Analysis (psychology revivals): New Directions for Psychology and Education. Routledge.

Page, J., and R. Thelwell. 2013. “The Value of Social Validation in Single-Case Methods in Sport and Exercise Psychology.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 25 (1): 61–71.

Sabat, J., and E. Gallagher. 2019. “Rules of Thumb in Household Savings Decisions: Estimation Using Threshold Regression.” Available at SSRN 3455696.

Shefrin, H. M., and R. H. Thaler. 1988. “The Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis.” Economic Inquiry 26: 609–643.

Thaler, R. H., and C. R. Sunstein. 2021. Nudge: The Final Edition. Yale University Press.

Todd Jr, T. M. 2019. “Behavioral Economics and The Impact of Message Framing on Financial Planning Intentions.” Doctoral dissertation.