Journal of Financial Planning: February 2026

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- This study examines the effectiveness of a simple savings heuristic—the savings-to-income multiple (SIM) ratio—in predicting individuals’ perceptions of retirement income adequacy.

- Traditional retirement planning methods often require extensive financial literacy and the ability to interpret complex projections, such as Monte Carlo simulations. Many individuals lack the tools or understanding to use these methods effectively.

- The study leverages a commonly promoted heuristic of recommended savings by income and age.

- Analysis is based on the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), using a final sample of 3,227 non-retired households aged 25 and older with reported income data.

- Results indicate that the simple savings-to-income multiple measure tracks well with people’s subjective feelings about current or expected retirement income.

- Not surprisingly, higher perception of retirement savings adequacy is also associated with using a financial planner, being married, educated, financially literate, and retired. Non-White households were less likely to report a sense of adequacy. The savings-to-income multiple is a valid and accessible heuristic for retirement planning, potentially improving consumer confidence and decision-making. It also offers actionable insights for financial educators and tool developers.

Stuart J. Heckman, Ph.D., is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® professional and Charted Financial Analyst. He serves as the Ph.D. program director at Texas Tech University’s School of Financial Planning. His research focuses on the professional practice of financial planning and financial decision-making under uncertainty, particularly among young adults and college students.

J. Michael Collins, Ph.D., is the Fetzer Family Chair in Consumer & Personal Finance and a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he directs the Center for Financial Security. His research on household finance, financial capability, and the impact of public policy on consumer decision-making is widely cited internationally.

Sonya Lutter,Ph.D., is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® professional and licensed marriage and family therapist. She serves as the director of financial health and wellness at Texas Tech University School of Financial Planning, where she leads curriculum and continuing education in the areas of financial psychology, financial therapy, and financial behavior.

Emily Koochel, Ph.D., AFC, CFT, BFA, is a behavioral financial expert and educator specializing in client communication and financial planning. With experience across academia and fintech, she bridges research and practice to empower advisers and clients alike. Dr. Koochel is heavily involved in tech solutions that incorporate psychology of financial planning science and behavior change.

Tairsa Mathews is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® professional and a student in the Texas Tech University School of Financial Planning doctoral program. Her research focuses on household financial decision-making, financial wellness, and financial behavior. She is also an instructor at Utah Valley University, where she teaches courses in retirement planning, investment management, and personal financial planning.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Retirement planning is inherently risky and uncertain, involving many variables. The common approach is to ask what level of income an individual or household would hope to achieve in retirement and use that as a starting point for time value of money calculations. The calculations require assumptions over an entire lifetime about inflation, rates of return, earnings growth, savings rates, work life expectancy, retirement age, and age of death. Even with Monte Carlo simulations that can allow these assumptions to vary, there is little evidence that consumers can understand and interpret these results in helpful ways (Garcia-Retamero et al. 2019).

Research shows that heuristics do very well in settings where there is a lot of uncertainty (Mousavi and Gigerenzer 2014). Combined with financial literacy and nudges, increased awareness of one’s situation has positive associations with increased action toward retirement saving (Garcia and Vila 2020; Lusardi and Streeter 2023). We posit that retirement planning is a setting full of uncertainty, and it might, therefore, be more useful to take a heuristic approach to guiding consumers. This approach might attempt to present more simplistic guidelines that are easy to understand and are likely to get close to adequate retirement savings. Fidelity (2025) provides an example of a simple heuristic approach with a single overarching goal: “save 10× your income by age 67.” To achieve that single goal, they develop saving guidelines for ages beginning at age 30 as a multiple of income. This approach is useful because most consumers can identify their annual income easily and it allows for simple adjustments. If they are under the benchmark, they need to save more to improve the likelihood of maintaining their standard of living. If they are over the benchmark, they may be able to choose between continuing their current level of saving and having a higher standard of living in retirement or reducing their saving and enjoying a higher standard of living now. To explore whether the savings-to-income multiple is a useful metric for consumers, we test whether the multiple is correlated with perceptions of retirement income adequacy in a national dataset from the United States.

Literature Review

Retirement planning remains a complex task for most households due to numerous uncertainties—fluctuating income, variable rates of return, changing inflation rates, and unknown longevity. Traditional planning methods, such as Monte Carlo simulations, are often inaccessible or incomprehensible to the average consumer. This complexity has created interest in simplified tools and heuristics that can guide financial behavior without requiring advanced expertise.

Planning is further complicated by a mix of defined contribution and defined benefit plans from multiple employers over the course of a lifetime, as well as any anticipated government retirement benefits. More than half of the U.S. adult population aged 18–64 is covered by some employer-sponsored account, according to data pooled by Sabelhaus (2022). The United States has been opting for workplace defined contribution plans over defined benefit plans since their inception in 1978 (McWhinney 2024). The European Union has also started the shift to defined contribution plans with a combined reliance on defined benefit plans (Hinrichs 2021).

Defined contribution plans can offer an attractive vehicle for savings. Contributions often reduce taxable income, accumulations are tax deferred, and many employers offer a match, for example, 50 percent of an employee’s contributions up to a threshold of their salary (e.g., 5 percent). Passing up “free” money, as it is often referred to, does not generally make much sense, yet surprisingly, not all eligible employees participate. Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) posit that this may be due in part to a lack of financial literacy. With the shift from pension plans, where most of the planning was done for the employee, to defined contribution plans, employees are now responsible for determining both whether and how much to save, shifting the responsibility for long-term financial choices onto the individual.

Heuristics have long been recognized for their potential to support decision-making under uncertainty (Mousavi and Gigerenzer 2014). In financial contexts, heuristics can reduce cognitive load and facilitate more timely and effective choices (Garcia and Vila 2020), although the use of heuristics can lead to situations where individuals fail to optimize planning-related decisions, such as investment allocations (Benartzi and Thaler 2007). An example of a heuristic that has proven inadequate is the income replacement ratio, which was shown to have low correlation with actual retirement readiness as it fails to capture consumption needs or variations in wealth levels (Burnett et al. 2018). Burnett et al. (2018) argue that more comprehensive metrics are necessary to adequately capture retirement income adequacy. Heuristics are generally based on data that accounts for the typical expectations and some volatility, with the assumptions used contributing to the accuracy and usefulness of the heuristic. For instance, the Fidelity savings-to-income multiple has several built-in assumptions. Namely, people are invested in an “appropriate” mix of securities for their age, have an ongoing 15 percent savings rate, a 1.5 percent constant real wage growth, a retirement age of 67, and a life expectancy of 93. The retirement income replacement rate is estimated at 45 percent of pre-retirement annual income but assumes no pension income. The lower replacement ratio is justified by assuming that people will claim Social Security benefits at age 67 (Fidelity 2025). According to research in Germany, to maintain income satisfaction requires higher replacement ratios for those with lower incomes (around a 75 percent income replacement ratio for a single person with a €1,000 monthly income), but lower replacement ratios for those with higher incomes (around 55 percent for a single person with a €4,000 monthly income—the pattern holds for married households) (Schmied 2023).

Despite criticism of heuristics for their lack of nuance, growing evidence suggests that well-designed guidelines or benchmarks can enhance financial literacy and outcomes, especially when paired with educational nudges. This paper investigates whether a commonly used heuristic, the savings-to-income multiple (SIM), correlates with subjective measures of retirement income adequacy. We then analyzed whether individuals whose actual savings align with heuristic benchmarks perceive their retirement income as more satisfactory. The objective is to provide simplified heuristics of savings to date; therefore, defined benefit plan benefits are ignored.

It is worth noting that the purpose of this paper was to evaluate one element (i.e., the savings-to-income multiple) relative to perceptions of retirement income adequacy. As noted by Chen and Wettstein (2025) and their analysis of multiple data sets, income and net wealth are not typically good discriminators in life satisfaction. What is important is spending patterns, debt management, and feelings of regret about not saving enough. The savings-to-income multiple may address elements of spending by capturing money saved relative to income at various life stages and could help people get more on track at an earlier age and feel more satisfied in retirement.

Methods

Sample

The data used for this study comes from the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a triennial survey sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board. The SCF employs a dual-frame sampling technique to oversample wealthy households and utilizes multiple imputations to estimate missing data and protect the privacy of respondents. The analyses began with the full sample (n = 4,595) to explore the research question. Data were then limited to a sample of respondents who are not retired, at least 25 years old, and report having household income. After those sample restrictions, the analytic sample included 3,227 households. Throughout this paper, raw sample proportions are reported rather than population-weighted proportions due to the sample restrictions.

Savings-to-Income Multiple

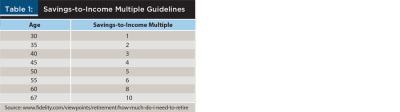

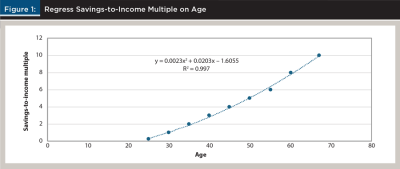

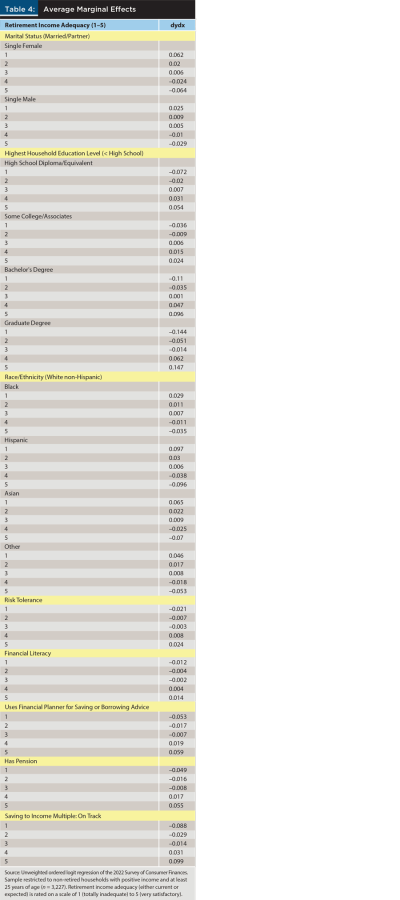

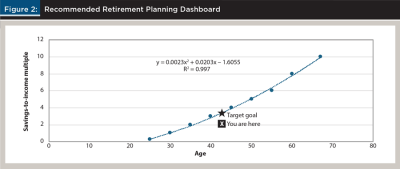

The analysis began with taking retirement savings guidelines published by Fidelity (see table 1) and fitting a polynomial regression line to estimate a relationship between age and the benchmark income multiple to determine a benchmark given any age. More specifically, table 1 provides the general benchmarks for being on track at various ages. To limit the number of predicted zero or negative values, an age 25 benchmark of 0.25 was added so that the predicted benchmark was positive. A second order polynomial was then used to fit the data points resulting in a prediction equation of y = 0.0023x2 + 0.0203x – 1.6055.

The explained variance of the resulting line was 0.997 as shown in figure 1.

To determine whether a household i is on track with the retirement savings heuristic, the actual savings-to-income multiple (SIMi) was divided by the benchmark savings-to-income multiple (SIMB) to determine the extent to which the household is on track with the simple retirement guideline. The ratio of the actual savings-to-income multiple for household i to the benchmark savings-to-income multiple ratio (i.e., SIMRi) should be greater than or equal to 1 if the household is at least on track (or better). That is,

The actual savings-to-income multiple was estimated for household i by taking financial assets divided by household income using the variables created by the Federal Reserve Board. For couple households, an average of the two ages was used to formulate a household average age for the purpose of determining the appropriate benchmark threshold. The SIMR is computed by dividing the household SIM by the benchmark SIM. Lastly, a binary variable indicates whether the household is on track (i.e., SIMRi > 1 ) or not (i.e., SIMRi < 1).

To illustrate the process just described, take Bob and Sue as an example. They earn $300,000 per year and have saved $1 million for retirement. Bob is 46 and Sue is 44. Their household age is 45. Their savings-to-income multiple (SIMi) is 1,000,000 / 300,000 or 3.33. We then applied the regression formula to calculate their benchmark savings-to-income multiple (SIMi):

(.0023 × 452) + (.0203 × 45) – 1.6055 = 3.97

Lastly, we then divide their actual savings-to-income multiple by their benchmark savings-to-income multiple to determine if they are on track for retirement or not: 3.33 / 3.97 = 0.84, which is less than 1, so they are not on track for adequate retirement income.

Retirement Income Adequacy

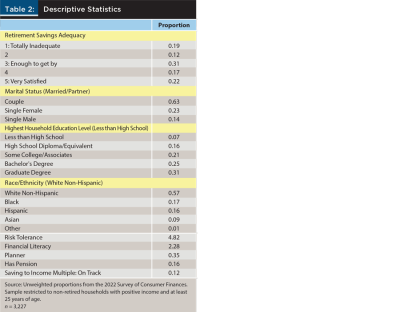

SCF respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with their current or expected retirement income. Specifically, variable X3023 asks, “Using any number from one to five, where one equals totally inadequate and five equals very satisfactory, how would you rate the retirement income you receive (or expect to receive) from all sources?” As shown in table 2, 22 percent of the sample reports a 5 (very satisfactory), 17 percent reports a 4, 31 percent reports a 3, 12 percent reports a 2 and 19 percent reports a 1 (totally inadequate).

Analysis

Using the 2022 SCF, we controlled for confounding factors to identify the relationship between the SIMR and retirement income adequacy by selecting variables that could reasonably be expected to be related to some component of the SIMR (e.g., age, income, assets) and also to the outcome (i.e., current or expected retirement income adequacy). Marital status, household education level (i.e., the highest level of education for individuals or among partners in couple households), race of respondent, risk tolerance, financial literacy, and whether the household has a pension enter the regression equation as control variables.

Based on the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, we utilized an ordered logit to estimate the relationship between the independent variable and control variables and the outcome. Given that the SCF uses multiple imputation to account for missing data and to protect the privacy of participants, we used the repeated imputation inference (RII) method to adjust the standard errors (see Lindamood et al. 2007; Montalto and Sung 1996; Montalto and Yuh 1998).

Results

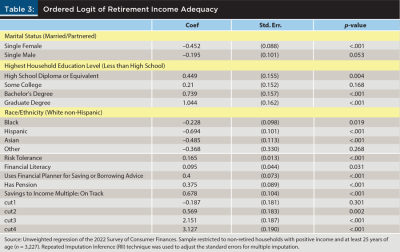

The results of the ordered logit, shown in table 3, indicate that being on track with retirement savings according to the savings-to-income multiple ratio is positively related to retirement income adequacy. As indicated by the average marginal effects shown in Table 4, those who are on track are 8.8 percentage points less likely to report that their expected retirement income is totally inadequate and 9.9 percentage points more likely to report that their expected retirement income is very satisfactory.

Other results indicate that married or partner households report more adequate retirement income than single households, with single female households significant at all levels, but single male households only significant at the 10 percent level. Education is positively related to retirement income adequacy. Individuals who earn a bachelor’s degree are 9.6 percentage points more likely to report retirement income is very satisfactory, and the completion of a graduate degree are 14.7 percentage points more likely to report very satisfactory retirement income. Risk tolerance, financial literacy, and use of a financial planner for saving or borrowing advice are positively related to higher retirement income adequacy. Those reporting financial planner use for saving or borrowing advice are 5.3 percentage points less likely to report their retirement income is totally inadequate and 5.9 percentage points more likely to report that their retirement income is very satisfactory. Non-White households are generally less likely to report adequate retirement income compared to White households. Lastly, retired households and households reporting a pension plan (where the employer bears the investment risk) are also more likely to report adequate retirement income.

Discussion

The results of the current study provide evidence that a simple savings-to-income multiple is related to perceptions of retirement income adequacy. This finding aligns with findings that in financial contexts, heuristics can facilitate more timely and effective choices (Garcia and Vila 2020; Lusardi and Streeter 2023). Dashboards that show the current savings-to-income multiple relative to a guideline may be helpful in simplifying feedback to the individual about whether they are on track or not. In other words, providing overly specific recommendations on retirement dashboards may lead to false assumptions of retirement preparedness among employees. The implications suggest a redesign of retirement dashboards to improve planning and retirement outcomes. We suggest a dashboard visual aid that represents figure 2 with a mark at the client’s age to indicate their current status as on track, ahead of, or behind the benchmark expectation.

The results also provide additional insight into the benefits of financial planner use in the perception of retirement income adequacy. The use of heuristics alone can lead to inadequate retirement readiness (Burnett et al. 2018), but the use of a financial planner can support clients in optimizing planning-related decision-making. With higher financial literacy and education also indicating higher likelihood of reporting adequate retirement income, financial planners can play an additional role to improve financial literacy among their clients to help them make financial decisions utilizing the savings-to-income multiple.

Limitations

As with any survey research, there may be concerns about the validity of self-reported data. Problems with the accuracy of self-reporting are minimized through the rigorous data collection process used by NORC—the SCF stands out as an authoritative source on the state of household balance sheets. However, the SCF does not provide information about the respondent’s personality or general disposition, which could certainly relate to the dependent variable in this study. Lastly, because the dependent variable is a subjective perception about the adequacy of expected retirement income, future research should consider exploring how the savings-to-income multiple tracks with objective retirement income adequacy. A longitudinal dataset, such as the Health and Retirement Study, would allow researchers to observe households pre- and post-retirement, which could provide evidence regarding the efficacy of the heuristic in terms of actual rather than expected outcomes.

Conclusion

In an environment where consumers struggle with the complexity of retirement planning, heuristics like the savings-to-income multiple provide accessible and effective guidance. The results of the study revealed a positive relationship between a simple savings-to-income ratio and perceptions of retirement income adequacy. Integrating a savings-to-income multiple indicator into financial planning tools and educational interventions, particularly when enhanced by visuals and personalized feedback, could be useful for planners and retirement plan providers. Professionals should also bear in mind that while heuristics may be especially helpful early in the life cycle and for clients with long time horizons before retirement, as clients near retirement, the more detailed retirement planning analyses and scenarios may provide more clarity and peace of mind.

While only an estimated 10 percent of U.S. adult workers are supported by a defined benefit plan, it is still important to note that pension benefits are not factored into this simplified indicator of retirement preparedness. Future research may want to consider adjusting the multiple to account for the present value of such benefits, knowing it introduces more complexity and uncertainty to the equation. Researchers should also explore how heuristics perform longitudinally and across diverse populations (e.g., between racial and ethnic groups), and account for non-financial or direct financial support received from social support systems.

Citation

Heckman, Stuart, J. Michael Collins, Sonya Lutter, Emily Koochel, and Tairsa Mathews. 2026. “Retirement Savings Heuristics and Perceptions of Retirement Income Adequacy.” Journal of Financial Planning 39 (2): 62–72.

Endnotes

- Respondents with retired spouses were also excluded.

- The Fidelity guidelines begin at age 30 and before age 25, individuals may be still completing education or otherwise navigating their first few years in the labor market. Income appears in the denominator of the actual and benchmark ratios, which would case the ratio to be undefined if income is zero. Given the multiple imputation in the SCF, we exclude households who report zero income in any implicate.

- Although there is procedure within Stata to simultaneously adjust for both the multiple imputation and the complex sample design of the SCF (see Shin and Hanna (2016) for a discussion), scfcombo does not work with ordered logit. Therefore, we present the RII-adjusted standard errors from the ordered logit and ran a robustness check using an OLS regression with scfcombo to adjust the standard errors via RII method and the Fed-provided replicate weight file to account for the complex sample design. Results were consistent and are available upon request.

References

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard Thaler. 2007. “Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (3): 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.3.81.

Burnett, John, Kevin Davis, Carsten Murawski, Roger Wilkins, and Nicholas Wilkinson. 2018. “Measuring the Adequacy of Retirement Savings.” Review of Income and Wealth 64 (4): 900–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12307.

Chen, Anqi, and Gal Wettstein. 2025. “A Review of Existing Measures of Retirement Well-Being Research Dialogue.” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College no. 25-6. https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IB_25-6.pdf.

Fidelity. 2025. How Much Do I Need to Retire? www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/how-much-do-i-need-to-retire.

Garcia, Jesus Maria, and Jose Vila. 2020. “Financial Literacy Is Not Enough: The Role of Nudging Toward Adequate Long-Term Saving Behavior.” Journal of Business Research 112: 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.061.

Garcia-Retamero, Rocio, Agata Sobkow, Dafina Petrova, Dunia Garrido, and Jakub Traczyk. 2019. “Numeracy and Risk Literacy: What Have We Learned So Far?” The Spanish Journal of Psychology 20:22: E10.

Hinrichs, Karl. 2021. “Recent Pension Reforms in Europe: More Challenges, New Directions. An Overview.” Social & Policy Administration 55 (3): 409–422.

Lindamood, Suzanne, Sherman D. Hanna, and Lan Bi. 2007. “Using the Survey of Consumer Finances: Some Methodological Considerations and Issues.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 41 (2): 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2007.00075.x.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia Mitchell. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing.” NBER Working Paper No. 17078.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Jialu L. Streeter. 2023. “Financial Literacy and Financial Well-Being: Evidence from the U.S.” Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing 1 (2): 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2023.13.

McWhinney, James. 2024. “The Demise of the Defined-Benefit Plan and What Replaced It.” Investopedia. www.investopedia.com/articles/retirement/06/demiseofdbplan.asp.

Montalto, Catherine P., and Jaimie Sung. 1996. “Multiple Imputation in the 1992 Survey of Consumer Finances.” Financial Counseling and Planning 7: 133–46.

Montalto, Catherine P., and Yoonkyung Yuh. 1998. “Estimating Nonlinear Models with Multiply Imputed Data.” Financial Counseling and Planning 9 (1): 97–103.

Mousavi, Shabnam, and Gerd Gigerenzer. 2014. “Risk, Uncertainty, and Heuristics.” Journal of Business Research 67 (8): 1671–1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.02.013.

Sabelhaus, John. 2022. “The Current State of U.S. Workplace Retirement Plan Coverage.” Pension Research Council Working Paper, PRC WP2022–07. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4049143.

Schepen, Arjen, and Martijn J. Burger. 2022. “Professional Financial Advice and Subjective Well-Being.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 17 (5): 2967–3004.

Schmied, Julian. 2023. “The Replacement Rate That Maintains Income Satisfaction Through Retirement: The Question of Income-Dependence.” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 26: 100471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2023.100471.