Journal of Financial Planning: December 2025

Philip DeMuth, Ph.D., is managing director of Conservative Wealth Management LLC (https://phildemuth.com) in Los Angeles and the author of 10 books on finance, most recently The Tax-Smart Donor: Optimize Your Lifetime Giving Plan.

NOTE: Click on the table below for a PDF version.

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

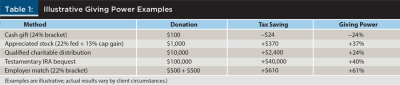

Charitable giving often comes as an afterthought in life cycle financial planning. These dollars seem to go out a side door in the financial plan, frequently in response to a year-end fundraising drive, but disconnected from broader tax, estate, and investment strategies. This article introduces “giving power,” a practical metric that measures the after-tax cost per dollar delivered to charity. Properly calculated and applied, giving power enables planners and clients to compare giving opportunities available currently, as well as across life stages. The result is a more strategic, life cycle-based approach to philanthropy that can amplify your client’s impact while minimizing their out-of-pocket cost.

Why a New Metric Matters

Ask a typical high-net-worth client how much they gave last year, and they’ll give you a number. Ask how much it cost them to donate that amount, and you’ll get a blank stare. Despite our sophisticated advances in tax planning and investment analytics, charitable giving remains orphaned from the rest of the client’s financial life, often guided more by emotion than deliberation and strategy.

Financial planners need a common yardstick to evaluate giving strategies. Giving power provides that measure. It can help you take your client’s gifting to the next level.

Defining Giving Power

Giving power answers: What does it cost me, after taxes, to deliver $1 to charity?

- A giving power of 0 percent means the gift is tax neutral.

- A positive giving power means the government is subsidizing the gift.

- A negative giving power means the donor is paying more than $1 after taxes to deliver $1 to charity. This is the outcome we want to avoid.

While the metric is straightforward, its implications are powerful: it enables donors and planners to compare giving methods on a level playing field.

Case Example: The $10,000 Gala Gift

A high-earning California couple writes a $10,000 check at a year-end fundraiser. They know there’s a charitable deduction available and assume this will be a significant one—possibly even an outright tax credit, making it a free gift to charity.

Planners know the reality is otherwise. The couple’s Schedule A state and local taxes are capped at $10,000 in 2025 (and they earn too much to receive any further relief from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which runs until 2030). They do get a $11,000 deduction from their 2 percent mortgage, and now they have a $10,000 charitable contribution to add to the pot. These items add up to $31,000, which is $500 less than what they can claim simply by taking the standard deduction.

Their $10,000 charitable gift costs them $15,030 (37 percent federal, 13.3 percent state): $10,000 for the gift, and $5,030 to pay the taxes. Giving Power: –50.3 percent.

If the couple had planned ahead and itemized strategically, the same $10,000 donation might have yielded a $4,970 tax benefit. Giving Power: +49.7 percent.

Notice how the tax swing between planning and no planning—$10,000—is as big as the gift itself. Yet the clients may never appreciate this. The tax bill arrives months later, a hefty return with an array of bewildering schedules. For all they can tell, their gift was fully deductible. This underscores the need for a clear metric like giving power at the point of decision.

While this example is extreme, consider a typical case: a couple in the 24 percent federal bracket and 6 percent state bracket. The giving power on their $10,000 charitable gift is either +30 percent in the best case with tax planning or –30 percent in the worst case under the standard deduction. There is an overall tax swing of $6,000 between these two outcomes.

Due to the confusing tax code, it is common for sophisticated clients to make rookie mistakes. Negative giving power is by far the most common scenario. Only 12 percent of taxpayers itemize; the other 88 percent take the standard deduction. Charitable gifts under this umbrella usually have a giving power equal to the negative of the client’s marginal federal + state tax rate.

It is not just moderate earners who struggle to optimize their deductions. In a 2021 letter, looking back on the difficulties he encountered with his own philanthropy, even Warren Buffett concluded that “all or a portion of philanthropic contributions can generate significant tax deductions for the donor. That benefit, however, is far from automatic.”

Applying the Metric in Practice

Giving power provides financial planners with a higher level of comparative measurement, transforming nominal or ordinal ranking into ratio-level data. The simplest use of giving power is to identify the best opportunity available at a single point in time (such as the current tax year).

In client meetings, giving power is best used comparatively:

“Donating $25,000 in appreciated stock costs you about $18,000 after tax, while donating the same amount from your checkbook costs closer to $30,000. You could be getting the same charitable impact for 40 percent less money, after-tax.”

Even a back-of-the-envelope calculation can make this advantage apparent.

Giving Power Across the Life Cycle

Now consider this situation: a young client visits a planner’s office and asks for the best way to give $10,000 to their favorite charity this year. The planner examines the various options and directs the client to the one with the highest giving power. Pleased with the result, the client comes back every year thereafter over the course of 50 years with the same request.

Then, sadly, the client dies. Attending the funeral, the planner reflects on how they helped the client donate half a million dollars to charity (50 years × $10,000) over their lifetime with maximum effectiveness.

But—is that accurate? By planning year by year, the adviser failed to take advantage of a life cycle perspective.

It could have been better had they engaged in a conversation like this:

“I notice that you are very charitably inclined. Instead of giving away the same amount every year, you could concentrate your giving in the years when your tax deductions will be the greatest. That would allow you to give more money to charity at a lower out-of-pocket cost just by letting Uncle Sam underwrite your giving.”

Financial planners are familiar with the general list of techniques that can lead to charitable deductions. However, the software suites they use—which can project retirement cash flows to the dollar and optimize complex trade-offs such as Roth conversions—are silent when it comes to long-term charitable planning. Until the technology catches up, advisers will have to make these kinds of estimates manually, perhaps assisted by hypothetical case queries to the rapidly improving AI models.

Giving power arithmetic demonstrates the overwhelming importance of taxes in giving. As a result, the financial planner should be central to the charitable conversation. Instead of giving simply because a development officer (who is just optimizing for the annual gift) has their hand out, it invites clients to be more thoughtful and intentional about their charity, and giving when it optimizes their own economic resources as viewed holistically under their life cycle financial plan. This enables the client to direct their capital exactly as they wish. The main beneficiary is their end charity; the main loser is the Internal Revenue Service.

Young Clients

Gifts from clients in their early careers typically do not qualify as itemized deductions, which means their giving power will be negative. Better uses for their early dollars include emergency funds, Roth IRAs, health savings accounts, 529 plans for their children, or saving for a down payment on a home. There are only a few exceptions: employer matching programs or windfalls of appreciated stock (such as from incentive stock options or restricted stock units) can sometimes provide ammunition for tax-advantaged giving. Otherwise, I advise younger people to give in small amounts or donate their time, while studying which charities they may want to support later when they are better situated to make larger donations.

Starting in 2026, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will allow non-itemizers to deduct $1,000 gifts to public charities ($2,000 married filing jointly) from their taxable income, which will enable them to donate tax-effectively up to these limits (provided they can otherwise afford to give).

Mid- and Late-Career Clients

Higher earnings and higher marginal tax rates create prime conditions for bunching deductions, compressing multiple Schedule A items into a single tax year and filling the standard deduction, thereby allowing charitable gifts to create positive giving power. Contributing appreciated securities to a donor-advised fund is typically the most effective way for clients to capture a charitable deduction, while avoiding future capital gains taxes, and fund multiple years’ worth of gifts to their targeted charities.

Retirees

Once required minimum distributions begin, qualified charitable distributions (QCDs) can deliver a giving power equal to the client’s combined federal and state marginal bracket because they completely bypass the standard deduction. Each dollar donated offsets ordinary income from their required minimum distribution that year, lowering their adjusted gross income (AGI), with possible beneficial side effects on Social Security taxation and the notoriously unpopular Medicare income-related monthly adjustment amounts.

Wealthy Seniors

For clients with larger estates, charitable giving offers a welcome alternative to paying the 40 percent estate tax. Giving while living creates a current-year income-tax deduction while reducing the size of the eventual estate. Testamentary gifts of IRAs (which receive no reset to fair market value upon the death of the owner) avoid the double taxation at both the estate and ensuing beneficiary levels.

For charitably motivated families with long time horizons, irrevocable charitable trusts can be a source of highly tax-advantaged giving that can be incorporated into their estate plans. These instruments are complex and should be developed in consultation with the family’s accountant, estate attorney, and financial planner (who, as fiduciaries, should be transparent with their clients about the costs of maintaining these structures, which may span decades).

Call to Action

Financial planning has successfully modeled the tax implications of retirement preparation, college funding, insurance planning, investment allocation, cash flow and budgeting, and estate planning. Charitable giving deserves the same rigor.

Giving power is not about which causes clients should support: it is about ensuring their generosity is deployed with maximum efficiency—the most charity for the least taxes. With tax law changes looming in 2026, it is time to integrate this metric into planning software, onboarding processes, and client conversations.

Why Giving Power Matters

- It respects tax reality. Tax costs or benefits are decisive for charitable planning. Whether a gift occurs above or below the AGI line, whether it offsets income tax or avoids estate tax, whether it triggers capital gains or avoids them—all these factors impact the cost of giving. Giving power captures these effects in a single number across all types of gifts, from clothes to Goodwill to the Picasso over the fireplace.

- It enables a life cycle strategy. Different life stages present different giving challenges and opportunities. Planners can time gifts to help clients optimize their tax leverage, not just today, but over their lifetimes. It rarely makes economic sense to donate when giving power is negative.

- It creates planning discipline. Advisers can help prioritize tactics: Should a client give cash now, stock later, or QCDs in retirement? Clients need this information to make the best decisions about the trade-offs. “Please don’t give without running it by me first” should be the mantra.

- It supports client psychology. Clients do not enjoy seeing their charity dollars needlessly diverted to Washington, D.C., to pay more taxes. Showing which methods produce the most impact per after-tax dollar can clear the way ahead, motivating greater generosity.