Journal of Financial Planning: November 2019

Mitch Anthony is the author of The New Retirementality (now in its fourth edition), Your Clients for Life, and Your Client’s Story. He is a popular keynote speaker who is widely recognized as a pioneer in financial life planning. He co-founded ROL Advisor, a company that equips financial advisers to facilitate Return on LifeTM conversations with their clients and prospects.

Lisa Kueng is director of creative campaigns at Invesco. She is co-author of Picture Your Prosperity: Smart Money Moves to Turn Your Vision into Reality.

Gary DeMoss is director of Invesco Consulting, a group dedicated to helping advisers get new clients, keep the clients they have, and grow their businesses.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

In 2018, the authors of this column embarked on a unique study sponsored by the Invesco Consulting Group with the goal of uncovering what was working—and what was not working—for those who had been in retirement for an average of seven years; a group we have dubbed “Retirementors.” The idea was to tap into this group to learn their retirement life lessons, and then pass those lessons along to those planning or just beginning their retirements—and the financial advisers who serve them.

The study profiled 500 retirees who had saved between $500,000 and $3 million in investable assets, 61 percent of whom had also employed a financial adviser in their retirement planning. In this column, we’ll discuss the top-level findings discovered in the study and some interesting insights passed on by study participants. The Retirementors study asked more than 100 questions covering allocation issues as well as the three areas discussed here: location, vocation, and vacation.

In subsequent columns, we plan to examine two critical retirement questions: “Should I stay or should I go?” and “What are the key attitudinal factors affecting your retirement experience?”

Balancing Purposeful and Recreational Activity

The original interest driving our research was to discover how retirees had negotiated the balancing act of purposeful (vocation) versus recreational (vacation) activity. Vacation is broadly defined as “leisure”—travel, hobbies, and recreational pursuits. We thought this research necessary, because other findings in the last decade have highlighted that the vast majority of retirees view retirement primarily as a phase during which leisure can be pursued, yet has also pointed out that there is a “law of diminishing returns” on leisure, thus creating a potentially conflicted situation.

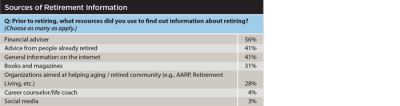

Another original interest driving the study was the role that financial advisers play as their clients plan for or engage in retirement. We found that a majority of respondents view their financial advisers as their No. 1 source for retirement information, with 56 percent reporting they rely on their advisers for such advice. This is higher than any other retirement information source, including AARP, online research, and advice from other retirees.

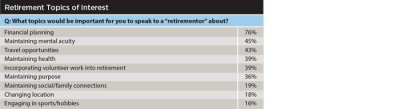

It is also interesting to note the areas of chief interest to those who are already retired. Financial planning is their top area of interest, followed by maintaining mental acuity and travel opportunities.

The Role of Work

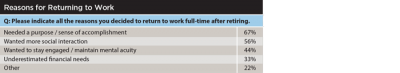

In the research questions around vocation, we inquired exhaustively into the arena of work and the role it plays for those who have retired in the last decade or so. If current trends play out, 26 percent of your clients who make an initial decision to stop working entirely will return to work. Our research tells us that a majority of them (56 percent) will make this decision within one year of retirement, and all of them will do so within five years.

Contrary to popular belief, in this demographic, the decision to return to work was not necessarily because they needed the money. Needing a sense of purpose, something to wake up and show up for, was four times more important than money for those who returned to work. Respondents commented that “time moves slowly if one is not actively involved in something interesting,” and that “it can get boring not having people around to talk with.”

Our research subjects wrote about returning to a range of work situations, including project-based work and consulting; teaching; art as a second career; real estate as a second career; and sports-oriented work such as part-time ski instruction or work at a golf course.

They also advised their peers to carefully consider their decision to leave work before taking action, suggesting that they should “back away slowly,” “do some soul searching” and “avoid quitting all at once because a slower transition allows for better adjustment.”

The findings support a common disconnect in retirement—that which exists between the lip service paid to the importance of purpose and the actual actions taken to pursue that purpose. It’s not unusual for a prototypical retiree to enthusiastically agree that it’s important to have something meaningful to do. Our research subjects advised other retirees to “find something you can get excited about,” to “find things that energize you,” and proclaimed that “you definitely need a reason to get up every morning.”

Yet when asked what they’re actually involved with, one of the most common retiree responses is, “Oh, I’m keeping busy,” at which point the real question becomes, “Busy doing what?” Is the texture of daily life for your retired and pre-retired clients purposeful, intellectually stimulating, and rewarding? For some, it is, as evidenced by this research, but for many, it is not.

Case in point: one of the planning meetings for this research was held at an offsite inn located in a residential neighborhood, with lots of windows facing out to the surrounding homes. As we were discussing this very topic, we noticed a retiree across the street with a leaf blower fastidiously clearing his driveway of what could not have been more than three leaves. He may have won the designation of cleanest driveway in town, but he was likely losing out on a true feeling of stimulation and satisfaction that day.

Seventy-seven percent of retirees surveyed look to fill in that need for stimulation and satisfaction with hobbies such as arts, crafts, music; 49 percent look to do so with sports such as golf and tennis. Yet, only 44 percent of those engaging in these activities report being passionate about them, and 27 percent describe them as “just something to do,” inferring a possible lack of visceral engagement or satisfaction with the activities they participate in.

Volunteering

Continuing with the theme of purpose, the Retirementors study found that volunteering provided the biggest “purpose payoff.” In the qualitative portion of our work, Retirementors made comments like, “I foster animals for the local animal shelter. Being retired gives me more time to devote to this work.” Others wrote of “volunteering on my condo board and using my skills there,” or doing research at the local university where “the young people keep me sharp.”

Regardless of the form it takes, 86 percent of those who volunteer in retirement report that doing so gives them that all-important sense of purpose. The purpose payoff was almost twice that of what hobbies provided. Despite the clear reward, a full 60 percent of the study participants

do not volunteer. Reasons why: 41 percent reported simply “not being interested,” and 25 percent said—perhaps somewhat ironically—they “were too busy to have time to help others.”

RetireMyths

One unintended consequence of the study was discovering a number of what we labeled “RetireMyths.” These are ideas around retirement that we’ve heard circulated in the past decade that our research simply did not support. Some of these myths include:

Retirees are going back to school to pursue advanced degrees/more education (only 7 percent thought about it).

A significant number of retirees are moving abroad (only 2 percent are).

Most retirees are going to move (most don’t move; 75 percent stay put).

Retiring means you no longer work (25 percent who made a decision to stop work entirely went back to work full- or part-time within five years).

Your expenses will decrease in retirement (37 percent indicated that expenses have not decreased and many indicate that they are increasing).

Clearly, retirement success is a highly personalized puzzle that each person must work out on his or her own. Everyone requires a place, a pace, and the proper space to make it work.