Journal of Financial Planning: May 2019

Fabio Ambrosio, J.D., LL.M., CFP®, EA, CPA/PFS, is an assistant professor of accounting at Central Washington University and a recurring lecturer at Swiss and Chinese universities. He is a former appeals officer in the estate and gift tax program at the IRS.

Editor’s note: This online appendix provides additional information and data related to the May 2019 Tax Planning Column “The Transfer Tax Tale of Disenfranchised U.S. Citizens.”

Introduction to the Possessions

The United States exercises sovereignty overall several territories and possessions, some of which most readers may have never heard of, such as Jarvis Island, Wake Island, Kingman Reef, and Johnston Atoll. Some of these territories have an independent form of government and tax code, while others do not.

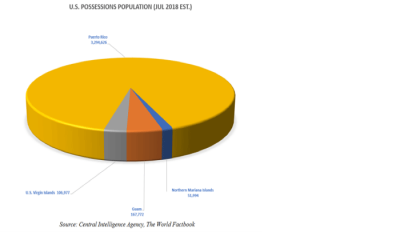

The term “United States” as defined under Title 81 includes only four such territories: Guam,2 the U.S. Virgin Islands,3 Puerto Rico,4 and the Northern Mariana Islands.5,6 Another territory, American Samoa, is considered to be an “outlying possession” of the United States.7 Under this distinction, persons born in Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, or the Northern Mariana Islands are considered U.S. citizens,8 while persons born in American Samoa are considered U.S. nationals.9

Because this article focuses on the transfer tax implications affecting people who acquired U.S. citizenship by birth in a U.S. possession, the discussion excludes U.S. nationals and is therefore applicable only to Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Northern Mariana Islands, which are collectively referred to as “the possessions.” More than 90 percent of persons residing in the possessions reside in Puerto Rico. Anyone who acquired U.S. citizenship by birth or citizenship in the possessions is hereinafter referred to as a “citizen of a possession” or collectively as “citizens of possessions.”

In general, U.S. federal law applies throughout the possessions with the most notable exception being federal tax law. The relationship between federal tax law and the possessions is complicated and fraught with special rules. While the definition of “United States” under Title 8 includes the possessions, the definition of “United States” in the Code includes only the States and the District of Columbia.10 As a result, the Code considers the possessions foreign countries and income from the possessions is taxed as foreign-source income.

Transfer Tax History and the Possessions

The estate tax was introduced in the United States by the Revenue Act of 1916.11 The Revenue Act of 1916 imposed a transfer tax as a percentage “of the value of the net estate” of every decedent “whether a resident or nonresident of the United States.”12 The “value of the net estate” was determined differently for residents and nonresidents. For residents of the United States, the term included the value of all property, wherever situated, subject to some deductions and an exemption amount of $50,000.13 For nonresidents, the term “net estate” included only property situated within the United States, subject to deductions based on the proportion of the estate situated within the United States, and without any exemption.14

The Revenue Act of 1916 defined “United States” as “the States, the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii, and the District of Columbia.”15 When the Revenue Act of 1916 was enacted, neither the U.S. Virgin Islands nor the Northern Mariana Islands had yet been acquired. While Guam and Puerto Rico had already been annexed through the Treaty of Paris on April 11, 1899, they had been excluded from the estate tax definition of “United States.”

The estate tax loophole in the Revenue Act of 1916 was glaring: because the tax applied only based on the residence of the decedent and the situs of the decedent’s assets, a U.S. resident could entirely escape the tax by: (a) taking up residency outside the United States; and (b) moving his/her assets outside the United States.

The Revenue Act of 193416 tried to correct the loophole by merely adding the word “citizen” alongside the word “resident” and the word “alien” alongside the word “nonresident.”17 Nothing else changed. As a result, the revised estate tax regime followed two alternative tracks: one for “a citizen or resident of the United States” and another for “a nonresident not a citizen of the United States.”18 These small revisions closed the loophole for those U.S. citizens who, prior to the amendment, took up residency in, and moved their assets to, a foreign country. For example, a U.S. citizen moving himself/herself and his/her assets to France would no longer escape the estate tax.

The Revenue Act of 1934 met a new challenge at the interplay with the Foraker Act.19 The Foraker Act of 1900 was passed shortly after the acquisition of Puerto Rico through the Treaty of Paris of 1898. The Treaty of Paris concluded the Spanish-American War, at the end of which the United States acquired Guam and Puerto Rico from Spain. The Foraker Act established limited independence and self-governance for Puerto Rico. At that time, Puerto Ricans were not granted U.S. citizenship but instead section VII of the Foraker Act established a separate Puerto Rican citizenship. As a result, a person could be a dual U.S. and Puerto Rican citizen.

How would the Revenue of Act of 1934 impose an estate tax on a dual citizen residing in Puerto Rico with assets only in Puerto Rico? Two cases were decided on this issue shortly thereafter.

In the first of the two cases, Estate of Smallwood v. Comm’r,20 the decedent was a U.S. citizen born in the contiguous United States21 who permanently relocated to Puerto Rico and acquired Puerto Rican citizenship. The government contended that, while not a resident of the United States, the decedent was still a citizen of the United States and therefore subject to the estate tax on all assets, wherever situated. The taxpayer contended that the definition of U.S. citizen for federal tax purposes did not include persons who were also Puerto Rican citizens, because “Congress has consistently maintained a benevolent policy in regard to Puerto Rico which it would not change by a general provision of an internal revenue law containing no specific reference to Puerto Rico.”22 The court agreed when it held that “[t]he Revenue Act of 1934, which merely added the word ‘citizen‘ alongside of the word ‘resident,‘ is not sufficient … to indicate a change in policy of Congress toward Puerto Rico and citizens thereof.”23 Therefore, despite being a U.S. citizen, the taxpayer was subject to estate tax as a non-citizen/non-resident only on assets situated within the United States.

In 1952 the Tax Court was called to decide a different spin to the same issue in Estate of Rivera v. Comm’r.24 The Rivera case brought the same estate tax considerations of Smallwood in the opposite context: that of a Puerto Rican citizen acquiring U.S. citizenship. While the Foraker Act established a separate Puerto Rican citizenship, in 1917 Congress passed the Jones-Shafroth Act,25 which granted U.S. citizenship to anyone born in Puerto Rico after the Treaty of Paris.26

The taxpayer in Rivera was born in Puerto Rico and acquired U.S. citizenship solely by virtue of the Jones-Shafroth Act. He lived in Puerto Rico his entire life until death. His estate was composed of tangible assets located in Puerto Rico and stock certificates issued by U.S. companies. Unlike Smallwood, where the government contended that dual citizens were in principal U.S. citizens, the government’s position in Rivera was the opposite: that the taxpayer was in principle not a U.S. citizen and therefore the estate tax applied to him as a non-citizen/non-resident only on assets situated within the United States. The Court of Appeals held that the estate could not be taxed as non-citizen/non-resident because the decedent was indeed a U.S. citizen.27 Further, the court noted, “we have been unable to find anything either in the changes in the estate tax law made by the Revenue Act of 1934, or in the committee reports or hearings relating thereto, which indicates that Congress intended to extend the estate tax law to Puerto Rico … Congress never intended to make the estate tax law applicable to the estates of deceased Puerto Ricans.”28

The combination of the holdings in Smallwood and Rivera opened two new loopholes. First, estates of U.S. citizens who, like Smallwood, acquired Puerto Rican citizenship and moved to Puerto Rico until death would be subject to estate tax only on assets situated within the United States, escaping the estate tax entirely if the assets were kept offshore. This offered a new loophole for U.S. citizens wishing to escape the estate tax. Second, estates of U.S. citizens who, like Rivera, acquired U.S. citizenship solely by virtue of the Jones-Shafroth Act would be exempt from all transfer taxes, even with respect to property situated in the United States because, as stated by the Rivera court, “Congress never intended to make the estate tax law applicable to the estates of deceased Puerto Ricans.”29

Congress passed the Technical Amendments Act of 1958 with the intent to “correct unintended benefits.”30 One such correction was the loophole created by the holding in Smallwood. Congress closed the Smallwood loophole by adding Section31 2208 and its gift tax counterpart, Section 2501(b), both of which clarified that U.S. citizens residing in the possession were still considered U.S. citizens for transfer tax purposes and thus subject to estate tax on their worldwide estate. Therefore, estates like Smallwood could no longer defeat the estate tax by taking up dual Puerto Rican citizenship. The 1958 amendments, however, did nothing to change the tax treatment of estates like Rivera, thus continuing then existing law that estates of those who acquired U.S. citizenship by virtue of the Jones-Shafroth Act would remain exempt from all transfer taxes, even with respect to property situated in the United States. Consequently, while estates of any other non-citizen/non-resident would be taxed on assets located in the United States, estates like Rivera continued to enjoy complete exemption, being taxed neither as citizens/residents nor as non-citizens/non-residents.

In 1960 Congress also closed the Rivera gap by amending the Code and adding Section 2209, which established that the estates of those persons who acquired U.S. citizenship by birth in a possession and resided on a possession at the time of death would be taxed as non-citizens/non-residents on assets located in the United States.32 Citizens of possessions were no longer exempt from transfer taxes.

The Disenfranchising Zone

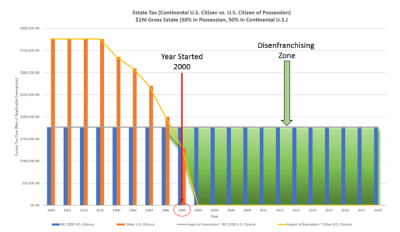

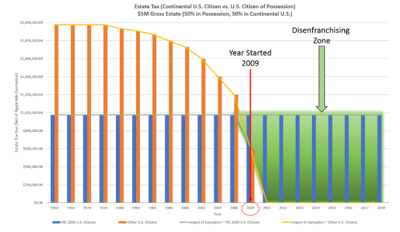

The yellow area in the chart below, labeled as Disenfranchising Zone, demonstrates the growing gap between the transfer tax exemption amount available to U.S. citizens and citizens of possessions. The exemption had stayed at $60,000 for all estates since 1942 and remained at $60,000 for all estates until 1976. Starting in 1977 the exemption amount for citizens/residents began to climb and has climbed steadily and steeply until reaching $11.2M in 2018. On the other hand, the exemption amount available to estates of non-citizens/non-residents remains $60,000.

The key factors in determining when citizens of a possession begin to be taxed less favorably than any other U.S. citizen in the same situation are: (a) the size of the unified credit available in the year of death; and (b) the proportion of wealth in the contiguous United States. If a given citizen of a possession holds half of his/her assets in the contiguous United States, the point in time where he/she began faring worse than any other U.S. citizen was the year 2000 for a gross estate totaling $1M, the year 2009 for a gross estate totaling $5M, and the year 2012 for a gross estate totaling $10M. Therefore, smaller estates were adversely impacted first.

Endnotes

- All references to “Title” are to titles of the United States Code.

- Guam and Puerto Rico were acquired through the Treaty of Paris on April 11, 1899.

- The U.S. Virgin Islands were acquired through the Treaty of the Danish West Indies on March 31, 1917.

- Guam and Puerto Rico were acquired through the Treaty of Paris on April 11, 1899.

- The Northern Mariana Islands were acquired through UN Security Council Resolution 21, which placed the territory under U.S. trusteeship from the end World War II until November 4, 1986, when the trusteeship ended and it formally became a U.S. possession.

- U.S. Code 8, § 1101(a)(38).

- U.S. Code 8, § 1101(a)(29).

- U.S. Code 8, § 1401.

- U.S. Code 8, § 1408. The main distinction between U.S. citizens and nationals is that U.S. nationals do not have a right to vote or hold office.

- U.S. Code 26, § 7701(a)(9).

- See Endnote 1.

- See Endnote 1, § 201, page 777.

- See Endnote 1, §§ 202, 203(a), page 777-778.

- See Endnote 1, § 203(b), page 778.

- See Endnote 1, § 200, page 777.

- Revenue Act of 1934, U.S. Statutes at Large 48 (1934): 680-772. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/73rd-congress/session-2/c73s2ch277.pdf.

- See Endnote 18, § 403, page 753.

- See Endnote 19.

- Foraker Act, Public Law 56–191, U.S. Statutes at Large 31 (1900): 77-86. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/56th-congress/session-1/c56s1ch191.pdf.

- Estate of Smallwood v. Comm’r, 11 TC 740 (1948).

- The working definition of “Contiguous United States” includes all those States located south of Canada and north of Mexico.

- See Endnote 22.

- See Endnote 23.

- Estate of Rivera v. Comm’r, 19 TC 271 (1952), affd. 214 F.2d 60 (2nd Cir., 1954).

- Jones-Shafroth Act, Public Law 64–368, U.S. Statutes at Large 39 (1917): 951-968. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/64th-congress/session-2/c64s2ch145.pdf.

- The issue of whether the Jones-Shafroth Act superseded or supplemented the Foraker Act is still alive. See Ramirez de Ferrer v. Brás, 144 D.P.R. 141, 1997 P.R.-Eng. 870,836, P.R. Offic. Trans.

- See Endnote 26.

- See Endnote 27.

- See Endnote 27.

- Technical Amendments Act of 1958, Public Law 85-866, U.S. Statutes at Large 72 (1958): 1606-1685. Accessed January 13, 2019. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-72/pdf/STATUTE-72-Pg1606.pdf.

- All references to “Section” are to sections of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, U.S. Code 26.

- Internal Revenue Ruling 74-25 later explained that the same tax treatment would apply to anyone who, having acquired U.S. citizenship by birth in a U.S. possession, dies residing in another U.S. possession.