Journal of Financial Planning: March 2016

Barbara O’Neill, Ph.D., CFP®, AFC, CHC, CFED, is a distinguished professor in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University and is Rutgers Cooperative Extension’s Specialist in Financial Resource Management. She has received more than 35 national awards for program excellence and over $985,000 in funding to support financial education programs and research.

Jing Jian Xiao, Ph.D., is a professor of consumer finance in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Rhode Island. His research interests include consumer financial capability, behavior, education, and well-being. He is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning.

Karen M. Ensle, Ed.D., RD, holds the rank of associate professor at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. She has been a family and community health sciences educator in Union County, New Jersey since 1987 and is a registered dietitian and fellow of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Editor’s note: This manuscript was passed through the Journal’s peer review process and subsequently accepted for publication prior to co-author Barbara O’Neill beginning her term as the Journal’s academic editor.

Executive Summary

- This article describes a study of the relationship of a self-reported planning behavior and the frequency of performance of positive health and financial management practices. The study uses data from an online survey of personal health and financial practices to examine whether respondents who have higher health behavior scores also have higher financial behavior scores.

- The conceptual base of this study is the Theory of Planned Behavior, which links intentions to perform behaviors with attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This theory has been found to be well supported by empirical evidence as a highly accurate and reliable way to predict human behavior.

- Correlation analysis was conducted between the health and financial behavior indexes. The correlation was 0.46 at a significance level of p < .05. This result suggests that desirable health and financial behaviors are moderately associated.

- Support was found for all three hypotheses in this study. Respondents who reported frequent planning behavior had higher health behavior scores than others. Respondents who reported frequent planning behavior had higher financial behavior scores than others, and respondents who had higher health behavior scores also had higher financial behavior scores.

A person’s propensity to plan is a trait that has been linked with successful financial and health outcomes (Ameriks, Caplin, and Leahy 2003; Lusardi and Mitchell 2006; Lynch, Netemeyer, Spiller, and Zammit 2010; Scholz, Sniehotta, Burkert, and Schwarzer 2007). This paper describes a study of the relationship of a self-reported planning behavior and the frequency of performance of positive health, such as eating low-fat foods, and financial management practices, such as spending less than income. It also uses data from an online survey of personal health and financial practices to examine whether respondents who have higher health behavior scores also have higher financial behavior scores. Findings from this study add to the knowledge base about associations between personal health and finances, and about personality traits associated with the performance of recommended practices.

Health and personal finance behaviors are strongly related in dozens of specific ways, including life expectancy and job productivity (O’Neill 2004; 2005; O’Neill and Ensle 2014). More than 2,000 years ago, the ancient Roman poet Virgil stated, “The greatest wealth is health.” As any financial planner can attest, accumulated wealth has limited value (other than providing access to quality health care services and resources for survivors) if someone is unhealthy and unable to enjoy it. Poor health also carries a large opportunity cost; namely, positive outcomes are forgone when people elect not to take care of their physical and mental health. People generally cannot build wealth if poor health and/or disability prevent them from working and earning an income (O’Neill 2015).

Unfortunately, about two-thirds of the U.S. population is overweight or obese, and some people sacrifice their health in the pursuit of wealth by failing to take positive actions on a daily basis, such as eating nutritious meals and engaging in physical activity. Poor financial practices have been found to be associated with physical symptoms of stress (Drentea and Lavrakas 2000; O’Neill, Sorhaindo, Xiao, and Garman 2005). Conversely, poor health practices have associated financial costs to both individuals and society. These costs drain funds that could otherwise be used for wealth accumulation and financial goal attainment. Economic effects of unhealthy behaviors include their initial direct outlay (for example, the cost of a pack of cigarettes or junk food), associated out-of-pocket medical expenses, and higher life and health insurance costs than those for healthier individuals.

This study was conducted to better understand the health and financial management practices of a large online convenience sample and their association with a measure of planning behavior. Implications are provided to inform financial planning practice. Financial planners are encouraged to consider clients’ personality traits, health practices, and personal finances holistically, because the strengths and challenges in one aspect of a client’s life often affect others. Like culture, health status is a lens through which to assess clients’ values, goals, and lifestyles. The same is true for personality traits, such as organizational skills, conscientiousness, and propensity to plan. When financial planners understand a client’s health status and personality traits, they can provide more comprehensive, individually targeted advice.

Literature Review

Planning behavior. Personality traits affect patterns of thinking and behaving. Traits are a set of organized characteristics held by individuals that are relatively stable over time and across various life situations (Nabeshima and Seay 2015). A study by de Rubio (2015) found that a long planning horizon plays an important role in explaining household asset accumulation and financial security. Households with heads who are older, white, male, with more years of education, and who are married have higher odds of having a longer planning horizon.

The latest Savings Survey (Consumer Federation of America 2015), like previous versions of this annual study, found people with a savings plan with specific goals save more successfully than those without a plan. The study found that people who are planners are goal-oriented, careful about spending money, and more likely than non-planners to make savings progress and have sufficient savings for emergencies and retirement. People who are planners may make daily or weekly to-do lists to keep track of the tasks they plan to accomplish, juggle their workload, meet deadlines, and schedule time wisely. Bird, Sener, and Coskuner (2014) grouped 374 Turkish respondents as “planners” and “non-planners” and found that planners fared better than non-planners in controlling consumer debt.

Ameriks et al. (2003) studied the financial impacts of a household’s propensity to plan and found that those with a higher planning propensity spend more time developing financial plans. They also noted that this planning is associated with increased wealth. The authors concluded that those who plan may be better able to control their spending and thereby achieve their goal of wealth accumulation.

Lynch et al. (2010) validated a six-item propensity to plan scale and also found that planning has pronounced effects on consumer financial behavior. A key finding was that FICO credit scores increased with a propensity to plan. Specifically, a one point increase in propensity to plan (on a six point scale) was associated with a 15.3 point increase in a person’s FICO score, holding the effects of all other predictor variables constant. Because those with lower FICO scores pay higher interest rates to borrow money, having a propensity to plan “has a very real effect on welfare through effects on the cost of credit” (p. 123).

Additional evidence of the positive impact of planning was found by Lusardi and Mitchell (2006) who studied the retirement preparation of two age cohorts at two points in time. Planners in both cohorts arrived close to retirement with much higher wealth levels and displayed higher financial literacy than non-planners, even after controlling for many sociodemographic factors. Lusardi and Mitchell concluded that differences in planning behavior helped explain why household retirement assets differed.

Spiller (2011) studied whether and how consumers incorporate opportunity cost considerations—such as determining the loss of potential benefits from alternative actions when a decision to do something is made—into decision-making. They found that perceived constraints cue consumers to consider opportunity costs. However, consumers with a high propensity to plan considered opportunity costs even when not cued by immediate constraints. Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) studied a specific type of advance plan called an “implementation intention” (for example, “If situation x arises, I will implement goal-directed response y”) and found implementation intentions to positively affect goal attainment.

During the past two years, several organizations have conducted research to classify people according to their financial practices in an attempt to identify the attributes of financially successful people to inform financial education and practice. Each entity has identified a positive constellation of personal financial characteristics with the following terms: financial well-being (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or CFPB); financial health (Center for Financial Services Innovation, or CFSI); financial capability (FINRA Investor Education Foundation); and financial wellness (@Phroogal, a financial education blog at www.phroogal.com for millennials that completed a 30-day “road to financial wellness” in June 2015). The terms financial well-being, financial health, and financial wellness refer to financial status outcomes (state of being), while financial capability refers to the performance of desirable financial practices.

All of these groups include goal-setting and future planning in their descriptions of financially successful people. For example, people who exhibit financial well-being “are setting goals that are important to them and working toward those goals whether or not they have a formal financial plan,” (Ratcliffe 2015), and “planning ahead for predictable life events” is a key component of financial capability according to the FINRA Investor Education Foundation (2013). The CFSI classified consumers into three financial health tiers: healthy, coping, and vulnerable. The former has three segments—thriving, focused, and stable—all of which have a long-term savings outlook associated with planning behavior (Gutman, Garon, Hogarth, and Schneider 2015).

Planning behavior also has positive effects on physical health. Scholz et al. (2007) examined age effects of two types of planning interventions: action planning (when, where, how), and coping planning (anticipating barriers and mental simulation of success scenarios). Findings indicated that coping planning facilitates improvement of physical exercise.

Keller and Siegrist (2015) developed a weight management strategies inventory (WMSI) to assess self-regulation strategies to control food intake and weight. A total of 19 weight management strategies were classified under five main WMSI categories, including “Prospection and Planning” (planning food purchases and regular meals and avoiding food temptations). These were found to correlate positively with dieting success. Planning behavior, including realistic goal-setting and self-monitoring, was also found to be associated with weight loss in a study by Hindle and Carpenter (2011).

Health and personal finance relationships. During the past decade, a number of studies have investigated relationships between personal health and financial behaviors. For a summary of research findings see O’Neill (2015) and O’Neill and Ensle (2014). In discussions of these studies, some researchers have noted that personal qualities may underlie positive health and financial practices. For example, in one study, employees received a workplace health screening. Researchers then followed workers for two years to see if they attempted to improve their health and whether changes were tied to financial planning. Retirement plan (401(k)) contributors showed improvements in health behaviors about 27 percent more often than non-contributors, despite having few health differences prior to the program (Gubler and Pierce 2014). The relationship between retirement savings and health practices was correlational. Time discounting preferences and conscientiousness were believed to be related to similarities between workers’ retirement contribution patterns and health improvement behaviors. Time discounting refers to the inclination of an individual toward current consumption over future consumption.

Studies have also explored the effect of health status on earnings and wealth. For example, Kosteas (2012) investigated the economic effects of engaging in regular physical activity and found a positive relationship between regular exercise and labor market earnings. Engaging in regular exercise (defined as working out at least three hours a week) was found to yield a 6 to 10 percent wage increase. Study results indicated that moderate exercise resulted in a positive earnings effect, and more frequent exercise generated an even larger impact. One possible reason may be that fit employees are highly disciplined and more productive, which can lead to career advancement and higher earnings.

Conversely, poor health habits, such as smoking, have been shown to be associated with negative effects on an individual’s financial situation. For example, Zagorsky (2004) found that the typical nonsmokers’ net worth is roughly 50 percent higher than that of light smokers and roughly twice the level of heavy smokers. He also found a negative relationship between body mass index and white female’s net worth (Zagorsky 2005).

Conceptual Background

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship of self-reported planning behavior and the frequency of performance of 18 positive health and financial practices. It also examined whether respondents who had higher health behavior scores also had higher financial behavior scores. The conceptual base of this study is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which links intentions to perform behaviors of different kinds (future planning) with attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen 1991; 2006). This theory has been found to be well supported by empirical evidence as a highly accurate and reliable way to predict human behavior.

Hypotheses. Based upon previous studies indicating positive associations between planning behavior and successful life outcomes, and between health and personal finances, this study had three hypotheses:

H1: Respondents who report frequent planning behavior will have higher health behavior scores than others.

H2: Respondents who report frequent planning behavior will have higher financial behavior scores than others.

H3: Respondents who have higher health behavior scores will have higher financial behavior scores.

Methodology

Data source. Data for this study came from the Personal Health and Finance Quiz (http://njaes.rutgers.edu/money/health-finance-quiz) believed to be the only publicly available online self-assessment tool designed to simultaneously collect data about individuals’ health and financial practices, versus proprietary tools developed by employee assistance programs and workplace wellness firms. Respondents rated their performance of health behaviors and financial behaviors on a scale, in which 1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = usually; and 4 = always.

Upon completion of the quiz, respondents receive a score for each section, a total score, and links to online resources. A high quiz score means that respondents are frequently performing many of the activities that health and financial experts recommend to improve health and build wealth, increasing their likelihood of success.

Experts in health/nutrition, personal finance, and evaluation methods provided input during the development of the Personal Health and Finance Quiz. This included both the format of the quiz and the selection of practices used to measure health and financial management. It should be noted that quiz behaviors are a “step in the right direction,” even if they are not at the highest recommended level of action. For example, most financial planners would agree that investing $3,650 annually is probably not sufficient for most workers to achieve maximum financial security in later life. However, investing the equivalent of at least $10 per day is far better than doing nothing, which, unfortunately, is the case for many Americans.

According to a recent Retirement Confidence Survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (Helman, Adams, Copeland, and VanDerhei 2014), 36 percent of American workers have less than $1,000 saved for retirement, excluding the value of a primary home and any defined benefit pensions. Equally alarming, 60 percent of Americans have total savings and investments of less than $25,000.

Variables. Planning behavior was measured by responses to quiz question 20: “I make written to-do lists or specific plans to organize my financial goals, spending, and/or daily activities.” Like the other quiz questions, responses were: never, sometimes, usually, and always. Health behavior was measured by the total score for nine health behavior questions (with a range from 9 for all “never” responses, to 36 for all “always” responses). Financial behavior was measured by the total score for nine financial behavior questions.

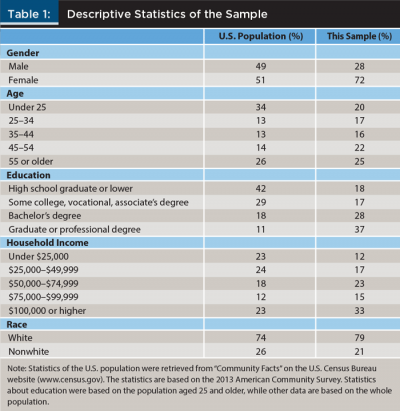

Sample. Data for this study were pulled for analysis in July 2015 on the one-year anniversary of the Personal Health and Finance Quiz. The sample had 944 observations. Excluding two cases with missing values, 942 observations were used in data analyses. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

As can be seen in Table 1, the sample is not reflective of the U.S. population, which is a limitation of this study. Rather, the sample was primarily white and female and had a higher educational and income level than typical Americans, with 65 percent of respondents holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 71 percent earning a household income of $50,000 or higher (versus a $51,939 median U.S. income in 2013). Only the age of respondents was more evenly distributed among the various ranges.

Results

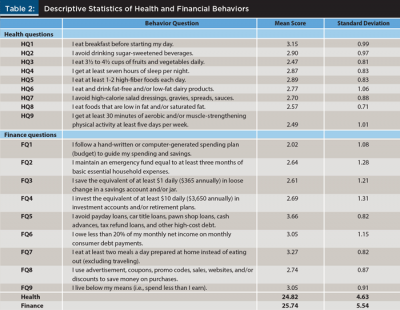

Descriptive statistics of the frequency of performance of health and financial behaviors reported by Personal Health and Finance Quiz respondents (N = 942) are provided in Table 2. The score of health behavior (Health) was the sum of responses to nine quiz questions (HQ1–HQ9) dealing with health practices. The score of financial behavior (Finance) was the sum of nine quiz questions (FQ1–FQ9) about financial practices. Question 20 on the online quiz was used as the planning variable in this study. This item, “I make written to-do lists or specific plans to organize my financial goals, spending, and/or daily activities,” received a mean score of 2.53 on the four-point rating scale.

A 10th health quiz question about drinking water was excluded from this analysis because it was later questioned by some health/nutrition experts and peer reviewers as not being the best indicator of positive health practice. This item was subsequently replaced with a statement about reading nutrition labels beginning with data collected in July 2015. This change followed publication of a study that found that individuals who engage in health information search behaviors, such as reading the contents and nutrition details of food labels, are more likely to engage in financial planning activities (Carr, Sages, Fernatt, Nabeshima, and Grable 2015).

The highest average score for a health quiz item was for eating a daily breakfast (M = 3.15), followed by avoiding consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (M = 2.90). The lowest average score for a health quiz item was for eating 3½ to 4½ cups of fruits and vegetables daily (M = 2.47) followed by getting at least 30 minutes of physical activity at least five days per week (M = 2.49).

The highest average score for a finance quiz item was for avoiding alternative financial services sector loans, such as payday and car title loans, and other high-cost debt (M = 3.66), followed by eating at least two meals a day prepared at home (M = 3.27). The lowest average score for a financial quiz item was for following a hand-written or computer-generated spending plan (M = 2.02), followed by saving the equivalent of $1 daily (M = 2.61).

A correlation analysis was conducted between the health and financial behavior indexes. The correlation was 0.46, which had a significance level p < .05 percent, suggesting that desirable health and financial behaviors are moderately associated, thereby providing some supporting evidence for H3.

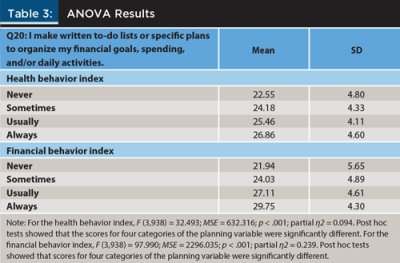

Table 3 presents mean scores for the health and financial behavior indexes by planning type (never, sometimes, usually, and always make plans). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis was conducted on the health behavior index by plan type. ANOVA is a statistical technique used to compare the means of three or more samples using the F distribution. The main effect of plan type was statistically significant, F (3,938) = 32.493; MSE = 632.316; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.094. Post hoc tests showed that, among the four categories of the planning variable, the scores of health behavior index were significantly different from each other. The results suggest that consumers who reported doing planning more often scored higher in the health behavior index.

The same ANOVA analysis was also conducted on the financial behavior index by plan type. The main effect of plan type was also statistically significant, F (3,938) = 97.990; MSE = 2296.035; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.239. Post hoc tests showed that, among the four categories of the planning variable, the scores of financial behavior index were significantly different from each other.

Based on these results, it was determined that consumers who reported doing planning more often scored higher than others in both the health and financial behavior indexes, providing supporting evidence for H1 and H2.

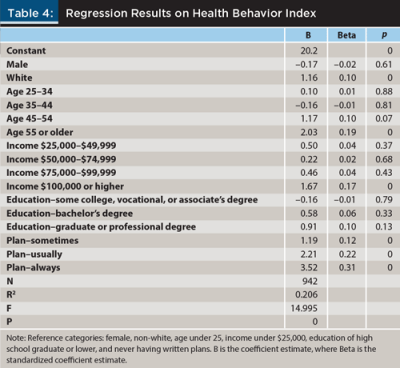

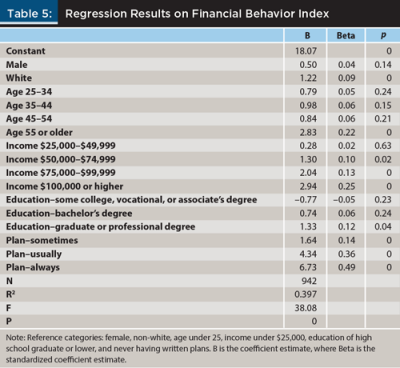

Multiple linear regressions were conducted to test if planning type makes a difference on health or financial behavior indexes by controlling for demographic variables. Tables 4 and 5 present the results. The results show that consumers who reported making financial and/or daily activity plans more often scored higher in both health and financial behaviors. For example, compared to consumers who reported “never” making financial plans, those who reported “sometimes,” “usually,” and “always” scored 1.19, 2.21, and 3.52 higher in the health behavior index, respectively. For the financial behavior index, compared to consumers who reported never making advance plans, those who reported “sometimes,” “usually,” and “always” increased their scores by 1.64, 4.34, and 6.73, respectively. These results provide supporting evidence for H1 and H2.

Based on Tables 4 and 5, several demographic variables were identified that show differences in both or either health and/or financial indexes. For both health and financial behaviors, whites scored higher than non-whites, but there was no gender difference. For health behavior only, consumers aged 44 and older (compared to those under age 25), and consumers with income of $100,000 or higher (compared to those with income under $25,000), scored higher, but there was no education difference. For financial behavior only, consumers aged 54 or older (compared with those under 25), those with an income of $50,000 or higher (compared with those with income under $25,000), and those having graduate and professional degrees (compared with those having high school or a lower educational level), scored higher.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between a self-reported measure of planning behavior and the frequency of performance of positive health and financial management practices using data from an online survey. It also examined whether respondents who had higher health behavior scores also had higher financial behavior scores. Support was found for all three hypotheses in this study. First, respondents who reported frequent planning behavior had higher health behavior scores than others. Second, respondents who reported frequent planning behavior had higher financial behavior scores than others. And third, respondents who had higher health behavior scores also had higher financial behavior scores.

The findings about the association of the frequency of planning behavior with health and financial management practices support previous research (Ameriks et al. 2003; Consumer Federation of America 2015; de Rubio 2015; Lynch et al. 2010; Lusardi and Mitchell 2006; Scholz et al. 2007).

The finding about the association of health behavior scores and financial scores supports previous research (Carr et al. 2015; Gubler and Pierce 2014; Kosteas 2012) and other “health and wealth” studies summarized by O’Neill (2015) and O’Neill and Ensle (2014).

Findings from this study make a unique contribution to the existing literature because relatively few studies to date have simultaneously investigated such a wide variety of individual health and financial practices. Most prior research has focused on just one key financial or health behavior, such as saving for retirement in a 401(k) plan, taking action to address physical health exam results, or reading nutrition labels.

Limitations

This study used data from an online convenience sample of respondents with different characteristics than the general U.S. population. However, sample characteristics more closely match the demographic profile of financial planning clients (Elmerick, Montalto, and Fox 2002). In addition, survey responses relied on respondents’ self-assessment of the frequency of planning behavior and of their performance of 18 health and financial management practices. These self-assessments could differ from an objective assessment by a neutral third party such as a financial planner. Nevertheless, the findings offer unique insights into the impact of a key personality trait—planning—upon personal health and finances.

Implications and Recommendations

Because the three hypotheses of this study were supported, there is evidence to suggest that clients’ organizational/planning skills and health behaviors are important factors to consider within the financial planning process. If clients do not indicate a propensity to plan, this skill can be fostered with strategies such as assigning tasks with deadlines, breaking large tasks down into small ones, and educating clients about organizational tools, such as to-do lists, whiteboard calendars, and smart phone apps. Planning behavior is not an inborn skill. People can learn to be better focused. Likewise, clients with health issues can learn about better health practices. Financial planners can frame this discussion with clients as reducing the risk of draining hard-earned wealth due to health expenses resulting from preventable causes.

The following are specific recommendations to foster improved planning skills and positive health and financial behaviors:

Given the positive associations among planning behavior and health and financial quiz scores, encourage clients to become better planners. In addition to benefits of “planfulness” identified in this study, other research has found that people who practice good planning tend to have a sense of control over their lives, cope better with stress, and feel happier than those who do not (Updegrave 2008).

Make planning as easy as possible for clients. For example, curating (collecting, organizing, and disseminating) and personalizing information, narrowing down viable options, and preparing forms for signature can go a long way toward reducing the “analysis paralysis” that can often accompany financial decision-making.

Empower clients with baby steps they could take to secure their financial future. An example of a helpful financial planning resource to do this is a graduated savings challenge, such as the popular 52-week money challenge. Savings begins with $1 during week 1 and rises to $52 during week 52, resulting in $1,378 of annual savings.

Encourage clients to better understand relationships between their personal health and finances. For example, if they practice healthy living habits, such as eating well and engaging in physical activity, they will probably have higher lifetime health care costs than unhealthy persons who often die at younger ages. This is due to more years of out-of-pocket expenses, an increased likelihood of contracting a chronic disease in later life, and the cost of long-term care (Sun, Webb, and Zhivan 2010).

Encourage clients to think holistically about actions they want to take to improve their lives. Not only are health and financial behaviors moderately correlated with one another, as indicated by the findings of this study, but the same behavior-change strategies can be employed to improve both aspects of people’s lives. Understanding the correlation between the two types of behaviors may be helpful in practice, because a person who is “planful” in health may also be “planful” in the domain of personal finance.

Apply behavioral science theories to help people develop desirable planning behaviors (Xiao 2008). For example, to encourage clients to develop positive planning behavior, 10 change processes based on the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross 1992; Xiao, O’Neill, Prochaska, Kerbel, Brennan, and Bristow 2004) can be used to help clients develop positive planning behaviors to reach specific long-term financial goals.

References

Ajzen, Icek. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211.

Ajzen, Icek. 2006. Behavioral Interventions Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Available online at: people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.intervention.pdf.

Ameriks, John, Andrew Caplin, and John Leahy. 2003. “Wealth Accumulation and the Propensity to Plan.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (3): 1007–1047.

Bird, Carolyn L., Arzu Sener, and Selda Coskuner. 2014. “Visualizing Financial Success: Planning Is Key.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (6): 684–691.

Carr, Nick A., Ronald A. Sages, Fred R. Fernatt, George G. Nabeshima, and John E. Grable. 2015. “Health Information Search and Retirement Planning.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 26 (1): 3–16.

Consumer Federation of America. 2015. Annual Savings Survey Reveals Across-the-Board Improvement in Past Year. Press release issued February 13, available online at: www.americasaves.org.

de Rubio, Alicia Rodriguez. 2015. “Factors Associated with Household’s Planning Horizons for Making Saving and Spending Decisions.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 43 (3): 284–292.

Drentea, Patricia, and Paul J. Lavrakas. 2000. “Over the Limit: The Association among Health Status, Race, and Debt.” Social Science and Medicine 50 (4): 517–529.

Elmerick, Stephanie A., Catherine P. Montalto, and Jonathan J. Fox. 2002.” Use of Financial Planners by U.S. Households.” Financial Services Review 11 (3): 217–231.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2013. Financial Capability in the United States: Report of Findings from the 2012 National Financial Capability Study. Available online at: www.usfinancialcapability.org.

Gollwitzer, Peter M., and Paschal Sheeran. 2006. “Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of Effects and Processes.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38: 69–119.

Gubler, Timothy, and Lamar Pierce. 2014. “Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Retirement Planning Predicts Employee Health Improvements.” Psychological Science 13 (3): 219–224.

Gutman, Aliza, Thea Garon, Jeanne Hogarth, and Rachel Schneider. 2015. Understanding and Improving Financial Health in America. Research paper for the Center for Financial Services Innovation. Available online at: www.cfsinnovation.com.

Helman, Ruth, Nevin Adams, Craig Copeland, and Jack VanDerhei. 2014. The 2014 Retirement Confidence Survey: Confidence Rebounds—For Those with Plans. Employee Benefit Research Institute Issue Brief No. 397.

Hindle, Linda, and Christine Carpenter. 2011. “An Exploration of the Experiences and Perceptions of People Who Have Maintained Weight Loss.” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 24 (4): 342–350.

Keller, Carmen, and Michael Siegrist. 2015. “The Weight Management Strategies Inventory (WMSI): Development of a New Measurement Instrument, Construct Validation, and Association with Dieting Success.” Appetite 92 (1): 322–336.

Kosteas, Vasilios D. 2012. “The Effect of Exercise on Earnings: Evidence from the NLSY.” Journal of Labor Research 33 (2): 225–250.

Lusardi, Annamarie, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2006. “Baby Boomer Retirement Security: The Roles of Planning, Financial Literacy, and Housing Wealth.” Journal of Monetary Economics 54 (1): 205–224.

Lynch, John G., Richard G. Netemeyer, Stephen A. Spiller, and Alessandra Zammit. 2010. “A Generalizable Scale of Propensity to Plan: The Long and the Short of Planning for Time and Money.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (1): 108–128.

Nabeshima, George, and Martin Seay. 2015. “Wealth and Personality: Can Personality Traits Make Your Client Rich?” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (7): 50–57.

O’Neill, Barbara. 2004. “Small Steps to Health and Wealth.” The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues, 9 (3) a refereed e-journal available at: ncsu.edu/ffci/publications/2004/v9-n3-2004-december/fa-1-small-steps.php.

O’Neill, Barbara. 2005. “Health and Wealth Connections: Implications for Financial Planners.” Journal of Personal Finance 4 (2): 27–39.

O’Neill, Barbara. 2015. “The Greatest Wealth Is Health: Relationships between Health and Financial Behaviors.” Journal of Personal Finance 14 (1): 38–47.

O’Neill, Barbara, and Karen Ensle. 2014. “Small Steps to Health and Wealth™: Program Update and Research Insights.” The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues 19 (1) a refereed e-journal available at ncsu.edu/ffci/publications/2014/v19-n1-2014-spring/oneil-ensle.php.

O’Neill, Barbara, Benoit Sorhaindo, Jing J. Xiao, and E. Thomas Garman. 2005. “Negative Health Effects of Financial Stress.” Consumer Interests Annual, 51: 260–262.

Prochaska, James O., Carlo C. DiClemente, and John C. Norcross. 1992. “In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Behaviors.” American Psychologist 47 (9): 1102–1114.

Ratcliffe, Janneke. 2015. “Four Elements Define Personal Financial Well-Being.” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau blog posted January 27 at www.consumerfinance.gov/blog.

Scholz, Urte, Falko F. Sniehotta, Silke Burkert, and Ralf Schwarzer. 2007. “Increasing Physical Exercise Levels: Age-Specific Benefits of Planning.” Journal of Aging and Health 19 (5): 851–866.

Spiller, Stephen A. 2011. “Opportunity Cost Consideration.” Journal of Consumer Research 38 (4): 595–610.

Sun, Wei, Anthony Webb, and Natalia Zhivan. 2010. “Does Staying Healthy Reduce Your Lifetime Health Care Costs?” Center for Retirement Research Working Paper 10–8.

Updegrave, Walter. 2008. “Save for Tomorrow, Be Happy Today.” Money Magazine, posted online September 24.

Xiao, Jing J. 2008. “Applying Behavior Science Theories in Financial Behaviors.” In J. J. Xiao (ed.). Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. New York: Springer.

Xiao, Jing J., Barbara O’Neill, Janice M. Prochaska, Claudia M. Kerbel, Patricia Brennan, and Barbara J. Bristow. 2004. “A Consumer Education Program Based on the Transtheoretical Model of Change.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 28 (1): 55–65.

Zagorsky, Jay L. 2004. “Does Smoking Harm Wealth as Much as Health?” Consumer Interests Annual 50: 108–116.

Zagorsky, Jay L. 2005. “Health and Wealth: The Late 20th Century Obesity Epidemic in the U.S.” Economics and Human Biology 3 (2): 296–313.

Citation

O’Neill, Barbara, Jing Jian Xiao, and Karen Ensle. 2016. “Propensity to Plan: A Key to Health and Wealth?” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (3): 42–50.