Journal of Financial Planning: January 2019

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is the founder of Goals Gap Planning LLC, delivering financial education to individuals and employer and professional groups.

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a state bar certified specialist in estate planning, trust, and probate law. She is the founder of Estate Plan Inc.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) temporarily doubled the estate tax exclusion from $5.49 million in 2017 to $11.18 million in 2018 ($11.4 million in 2019). In 2026, the exclusion reverts to the 2017 amount, adjusted for inflation. This potential exclusion creates the possibility of “clawback,” the automatic imposition of estate tax on those who made gifts protected by the doubled exclusion and then died after 2025 when the estate tax exclusion is lower.

To address clawback concerns, in the TCJA, Congress directed the Treasury Department to issue regulations “as may be necessary or appropriate to carry out section 2001 with respect to any difference between the basic exclusion amount applicable at the time of the decedent’s death and the basic exclusion amount applicable with respect to any gifts made by the decedent.” (Access the full text of the act at govinfo.gov.)

The Treasury Department issued the mandated guidance on Nov. 20, 2018 in the form of proposed regulations 20.2010-1(c)(3).

The proposed regulations offer good news and bad news. The good news is the regulations provide certainty with regard to clawback by allowing the decedent to claim a basic exclusion amount of the higher of: (1) the basic exclusion at death; or (2) the sum of the basic exclusion amounts applied to post-1976 gifts.

The bad news is the donor/decedent is treated as using his or her full exclusion amount if the gifts made during the higher-exclusion period exceed the post 2025-exclusion. In other words, if the decedent owns any property after 2025, the decedent will automatically owe estate tax on the property at the applicable rate (currently 40 percent).

Excerpts from the Proposed Regulations

Here is the applicable language from the proposed regulation (access the full text on the Federal Register at federalregister.gov):

“If the total of the amounts allowable as a credit in computing the gift tax payable on the decedent’s post-1976 gifts … exceeds the credit allowable … in computing the estate tax, … then the portion of the credit allowable in computing the estate tax on the decedent’s taxable estate that is attributable to the basic exclusion amount is the sum of the amounts attributable to the basic exclusion amount allowable as a credit in computing the gift tax payable on the decedent’s post-1976 gifts.”

Here is the example from the proposed regulations:

“Individual A (never married) made cumulative post-1976 taxable gifts of $9 million, all of which were sheltered from gift tax by the cumulative total of $10 million in basic exclusion amount allowable on the dates of the gifts. A dies after 2025, and the basic exclusion amount on A’s date of death is $5 million … . Because the total of the amounts allowable as a credit in computing the gift tax payable on A’s post-1976 gifts (based on the $9 million basic exclusion amount used to determine those credits) exceeds the credit based on the $5 million basic exclusion amount applicable on the decedent’s date of death, … the credit to be applied for purposes of computing the estate tax is based on a basic exclusion amount of $9 million.”

Individual A would not owe estate tax due to the add-back of adjusted taxable gifts but, if A owned $1 million of property at death, A would owe $400,000 of estate tax because there would be no exclusion left to shelter the property owned at death.

Individuals who take advantage of the higher exclusion amounts between 2017 and 2025 will need to wait for inflation adjustments to the 2017 basic exclusion to exceed the sum of their gifts and the property owned at death. (See the table below.)

In other words, Individual A from the regulation example will have to live until 2042 when the basic exclusion amount, adjusted for inflation, exceeds the $9 million exclusion amount (unified credit) used to avoid gift tax before he or she will have excess exclusion (unified credit) to offset estate taxes on property owned at death. An individual who uses the maximum projected exclusion of $12.84 million to avoid gift tax before 2025 will have to live until 2061 before his or her inflation-adjusted exclusion amount will start to shelter property owned at death.

Married Couples Have an Advantage

The proposed regulation example refers to the basic exclusion amount, not the applicable exclusion amount which also includes the portable exclusion (deceased spousal unused exclusion, or DSUE). The DSUE elected by a surviving spouse is not affected by the scheduled reduction in exclusion amount in 2026.

In other words, using numbers from the table of basic exclusion amounts below, if the first spouse dies in 2019, and the surviving spouse files a Form 706 to elect a DSUE of $11.4 million, the surviving spouse’s applicable exclusion amount in 2026 is $17.96 million ($11.4 million plus the projected $6.56 million basic exclusion amount). The $11.4 million DSUE does not decrease to $6.56 million after 2025.

Furthermore, married couples can engage in tandem strategies. For example, assume John, age 70, and Mary, age 65, think John will likely die first. In 2019, John could make gifts of $11.4 million. When he dies in 2030, the tax due on the adjusted taxable gifts he made in 2019 will be offset by the credit claimed in 2019, and he can avoid estate tax on any additional property he owns by using the marital deduction to pass the property to Mary.

Alternatively, Mary, who is expected to live longer, could make the large gift transfer in 2019, using all the credit related to her exclusion amount. When John dies in 2030, he could pass all the property he owns to Mary using the marital deduction, and Mary could file a Form 706 for John electing a DSUE of $7.1 million to add to the basic exclusion amount of $11.4 million from the add-back of her adjusted taxable gifts.

In other words, they could use the basic exclusion amount of one spouse or the other to maximize the gifts during the high exclusion period and have the other spouse’s basic exclusion amount as a reserve to avoid tax on any property they still own at death. If the marriage is unstable, the couple could split gifts up to $11.18 million (not $22.36 million), adjusted for inflation, and still each have a reserve to cover property owned at death going forward.

Strategies for the Ultra-High Net Worth

For the ultra-high net worth, the proposed regulation opens the gates to advanced planning strategies. Outright transfers to loved ones will work, but most clients will prefer to use irrevocable trusts. Single individuals may benefit from domestic asset protection trusts (DAPTs) established in one of the 17 states that allow them. A transfer to a DAPT is a completed gift that avoids estate tax, allows discretionary distributions to the grantor, can include generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax/dynasty trust provisions for the remainder interest and, of course, protects the trust assets from the grantor’s creditors when the conditions of the applicable state statute are met.

Married couples may prefer non-reciprocal spousal lifetime access trusts (SLATs). Each spouse can establish a trust for the other spouse’s life that will not qualify for the marital deduction, provide a stream of income for the other spouse, with the remainder going to the grantor spouse’s beneficiaries while taking advantage of the grantor spouse’s GST tax exemption, and offer asset protection. For this technique to work, it is important that: (1) neither the spouses nor their immediate relatives serve as trustees of the trusts; and (2) the terms of the trusts are substantially different from each other.

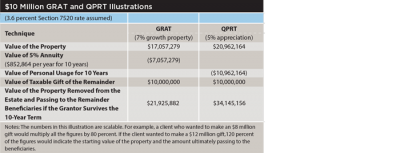

Exemption leveraging strategies, such as grantor-retained annuity trusts (GRATs) and qualified personal residence trusts (QPRTs), will also be popular. With a GRAT, the grantor transfers property to a trust and retains an annual annuity for a term of years shorter than the grantor’s life expectancy. The remainder is a taxable gift that passes to the grantor’s loved ones at the end of the term. The value of the gift is the property’s fair market value less the value of the retained annuity, which is discounted based on the federal government’s Section 7520 rate (3.6 percent in December 2018).

By adjusting the amount and payment period of the annuity, the size of the gift can be increased or decreased. A QPRT is similar to a GRAT, except the grantor’s primary residence (and possibly an additional residence) is transferred to the trust. The retained annuity is the personal use of the home(s) for the specified term(s). See the table below for an illustration.

Other Factors to Consider

The proposed regulation’s “use it or lose it” coupled with “if you do use it, you lose it for years to come” approach creates the need for more analysis.

The first question is: which clients are impacted by this issue? Assuming a 7 percent growth rate, any client with current net worth in excess of $3.56 million ($7.12 million for a married couple) is looking at the possibility of estate tax in 2026, if the law does not change.

Other factors, such as income tax basis planning, likelihood of transferred propety being sold, life expectancy, and making sure the donor has a means of support that will not be included in the estate, also come to mind. But perhaps the biggest question is: will the exclusion amount decrease in 2026? Except for a brief moment in 2013, the exclusion has not decreased before, but the political parties are split on whether the exclusion should be high or low.

With uncertainty, unless death is likely to occur before 2026, many clients will choose the “wait and see—look for the signals” approach, perhaps even waiting until the end of 2025 to implement a strategy. The presidential elections in 2020 and 2024 may offer some clues to whether the exclusion will revert to 2017 levels, continue at the current level, or change in some other way.

The Treasury Department is to be commended for issuing guidance on this controversial subject within one year of major legislation. It is still possible to make comments on the proposed regulations, which the Treasury Department could incorporate into the final regulations. Comments can be submitted online at regulations.gov. In the meantime, we should be encouraging our clients who are likely to be subject to estate tax to start thinking about next steps.