Journal of Financial Planning: January 2012

Executive Summary

- Many factors affect the decision of when to file for Social Security benefits, including health, personal financial considerations, and employment status. If clients can be flexible in their decision, planners should help them assess the financial advantage of the options available. One method of assessing the financial advantage is to calculate the break-even age. Break-even is the age when total Social Security income from two retirement options is the same.

- Using break-even calculations, we compare three basic options for when to start collecting Social Security benefits: (1) age 62, (2) full retirement age, which in our examples is assumed to be age 66, and (3) age 70. The calculations are highly dependent upon the numeric value of the variables used in the computations. These variables include the assumed rate of inflation, the return on investment, and marginal tax rates.

- Based on statistical averages, if the worker is the only person entitled on the account and the earnings test is not involved, the rate of return must generally exceed the rate of inflation by 5 percent or more to justify taking benefits at age 62 rather than at full retirement age. At higher inflation rates and/or higher marginal tax rates, the rate of return may need to be even higher, perhaps in excess of 7 percent or 8 percent above inflation to justify taking benefits at age 62.

- The rate of return needs to exceed the rate of inflation by a lesser amount to justify taking benefits at full retirement age rather than waiting until age 70. It may make sense for a man to start collecting benefits at full retirement age rather than waiting until age 70 if the rate of return exceeds the inflation rate by as little as 3 percent. For a woman whose life expectancy is longer, the rate of return would need to exceed inflation by 5 percent or 6 percent. At higher inflation rates and/or higher marginal tax rates, the rate of return may need to be higher.

- The break-even calculation is also affected by the number of other beneficiaries entitled on the worker’s record and/or whether the worker is entitled on multiple records.

- Every client’s situation is unique. The planner may use the information in this paper to assist clients in conducting break-even calculations tailored to individual circumstances.

Doug Lemons retired from the Social Security Administration as a deputy assistant regional commissioner after 36 years of federal service. He is currently working toward his CFP certification.

Deciding when to start collecting Social Security benefits is a major decision that will affect clients and their families for the rest of their lives. It is a complicated decision with many moving parts, including health factors, family longevity, personal financial considerations, and/or occupational vicissitudes. Clients may want to delay taking Social Security to ensure that they do not run out of money in their later years. Conversely, maybe the quality of their early years in retirement would be sacrificed by waiting until later to file for benefits. This decision can become particularly complicated in situations in which the worker is entitled to more than one benefit, when other family members are on the rolls, or when work is involved. A final consideration is the amount of widow(er)’s benefits payable to a surviving spouse in the event of a worker’s death.

Background

A refresher on certain key concepts relating to Social Security is needed to begin this examination. Full retirement age (FRA) is age 66 for people born between 1943 and 1954, and gradually rises to age 67 for people born in 1960 or later.1 The primary insurance amount (PIA) is the dollar amount a worker receives if he or she waits until full retirement age to start collecting Social Security. The PIA is different for each worker depending on various factors. Although the calculation of the PIA is beyond the scope of this paper, the Social Security Administration does provide this information on its website.2 In addition, clients may obtain an estimate of their own PIAs with Social Security’s online retirement estimator.3

A worker may start retirement benefits as early as age 62, or choose a month of entitlement (MOE) to benefits in any month up to age 70.4 The PIA is actuarially reduced for age for each month a worker collects benefits prior to FRA. Someone born between 1943 and 1954 who files for benefits at age 62 will have his or her PIA reduced by 25 percent—this is the reduction for someone who files for a retirement benefit 48 months prior to full retirement age.5 A worker’s PIA may also be increased by waiting to take benefits after full retirement age. A worker gets extra credit—called delayed retirement credits—by waiting to take Social Security after FRA. Someone can wait to start receiving benefits as late as age 70 when the benefit amount is the highest. There is no advantage to waiting beyond age 70 because benefits do not increase any further. For someone born in 1943 or later, the amount of the delayed retirement credit is 8 percent of the PIA for each year beyond full retirement age until age 70, for a maximum credit of 32 percent.

Work and earnings may affect benefits of someone who collects Social Security prior to FRA. In the years before full retirement age, benefits are reduced by $1 for every $2 of earned income above $14,160 (2011). In the year someone reaches FRA, benefits are reduced by $1 for every $3 of earned income above $37,680 (2011). Once someone reaches FRA, there is no earnings limit. There is no advantage to starting Social Security before FRA for someone who earns enough income to prevent him/her from collecting benefits.

According to the Social Security Administration, more than 73 percent of the population start taking benefits before FRA.6 Although everyone’s situation is unique, this is not necessarily the most financially advantageous time to start benefits, particularly for those who can be flexible in their decision. If a client does not need the income immediately, is it more advantageous to claim benefits early or wait until later to start collecting Social Security? Break-even calculations tailored to individual circumstances can help answer this question.

Break-Even Calculations

The break-even calculation compares two or more options for claiming benefits. Break-even occurs at the age when the total Social Security income from two options is the same. Other researchers have used this analytical tool, such as Rose and Larimore (2001) and Muksian (2004, 2006). I expand on some of this research by considering variables that affect the break-even calculations through analyses of increasingly complex case studies. The variables include inflation, taxes, and the time value of money. To illustrate the conclusions I have created Excel spreadsheets that incorporate these variables.

This paper compares the option of starting benefits at age 62 with starting at age 66, and the option of starting at age 66 with starting at age 70. These time frames are used because they are key dates for reasons explained above. However, comparing other months of entitlement is also possible. In all of the examples I presume that the earnings test is not a factor, because individuals who are still working may not be as likely to consider the option of filing for benefits prior to FRA.

The Analysis Begins

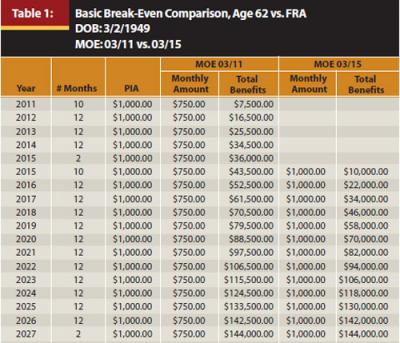

A worker born March 2, 1949, is considering retirement at age 62 with a month of entitlement (MOE) of March 2011, versus retirement at age 66 with an MOE of March 2015. His reduced Social Security Benefit at age 62 is $750. If he waits until full retirement age at 66 he receives $1,000. By taking the lesser benefit now, his benefit is permanently reduced by 25 percent or $250 per month. Let us enter the information into a spreadsheet that will be used for all future scenarios (see Table 1). Although the worker in our example was born in 1949, the calculations would apply to anyone whose full retirement age is 66—someone born between 1943 and 1954.

Basic information is entered into the first column. The “# Months” column shows the number of months in the calendar year for which benefits are paid. The PIA is the dollar amount of a worker’s Social Security Benefit at full retirement age. The column labeled “MOE 03/11” shows the monthly amount along with the accumulated total benefit amount. At the end of 48 months or in February 2015, the month prior to full retirement age, the individual will have accumulated $36,000. This is the initial monetary advantage gleaned from filing for benefits at age 62. The last column, “MOE 03/15,” compares the monthly benefit amount and the total benefits accumulated if the individual files for Social Security at full retirement age, in this case 03/15. You may compare the total benefits accumulated year by year. At the end of February 2027, or 144 months after full retirement age, the two amounts are the same—$144,000 total accumulated benefits. This is the break-even point. For each month after February 2027, the accumulated benefit amount is greater for an MOE of 03/15 than it is for an MOE of 03/11.

Social Security benefits are designed to be actuarially equivalent for someone with average mortality. Theoretically, it should not make a difference when an individual starts collecting benefits. However, external factors may affect the actual amount of benefits received. These factors include (1) inflation as measured by annual cost-of-living increases, (2) the time value of money of taking benefits early and investing that amount, and (3) taxes.

Inflation and Cost-of-Living Increases

Beginning in June 1975 Social Security benefits have been adjusted for inflation annually. This inflation adjustment is referred to as a COLA (cost-of-living adjustment). Except for 2010 and 2011, benefits have increased every year since 1975 based on the consumer price index (CPI). The worker’s PIA at age 62 is increased each year commensurate with the COLA regardless of when he starts receiving benefits. If the worker’s PIA at age 62 is $1,000, and the subsequent year’s COLA is 3 percent, his PIA is increased to $1,030 the next year. Individual scenarios assume a constant inflation amount, although the spreadsheets could accommodate variable annual inflation figures.

The net effect of inflation in the break-even calculation is to reduce the break-even age. This is because the amounts used to recover the initial financial advantage are inflated dollars. In the example above, if inflation increases 3 percent each year, the break-even age is reduced to 118 months after age 66. This is 26 months sooner than the non-COLA-adjusted calculation.

Return on Investment

Taking Social Security earlier allows a client to invest the proceeds at some compounded interest rate. This return on investment should be taken into account. If inflation reduces the break-even age, the return on investment stretches it out. Individual scenarios assume a consistent return on investment, although spreadsheets can be designed for variable returns. Our calculations presume that benefits, once received, are invested in interest-bearing accounts and allowed to accumulate until the break-even point.

Income Taxes

Income taxes should also be taken into consideration. Taxes reduce the overall rate of return on investment. Current federal marginal tax rates may be as high as 35 percent. In addition, Social Security benefits can be federally taxed on as much as 85 percent of the yearly benefits received. Our calculations presume that every dollar of Social Security benefits is taxed at the marginal tax rate, which may not be the case, particularly for lower income beneficiaries. We further assume that earnings from accumulated savings are in the form of taxable interest rather than dividends or tax-exempt interest. As with the other variables, spreadsheets can be developed to accommodate tax-advantaged investments.

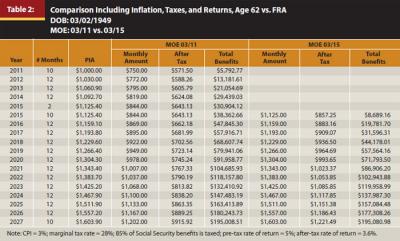

Continuing with the previous example, let us assume a marginal tax rate of 28 percent and that adjusted gross income is high enough so that 85 percent of Social Security benefits is taxed. If the nominal interest is 5 percent, the after-tax rate of return on earnings is 3.6 percent, or 5% x [1 – (28%/100)]. As shown in Table 2, the after-tax initial financial advantage in our example is $30,904.12. This initial advantage is recovered in 152 months (October 2027) or a little over 12½ years when the individual is about age 78½.

We arrive at the same results if we assume all of the benefits received from taking early retirement are invested at the designated interest rate; then, when the worker reaches full retirement age, he starts spending at a dollar amount equal to the monthly benefit rate he would have received had he taken the later retirement date. In other words, in March 2015 the worker has saved $30,904.12, and his tax-adjusted monthly benefit amount is $643.13. If he then starts spending $857.25 per month, an amount equal to his tax-adjusted monthly benefit if he waits until FRA, he will exhaust his savings in October 2027.

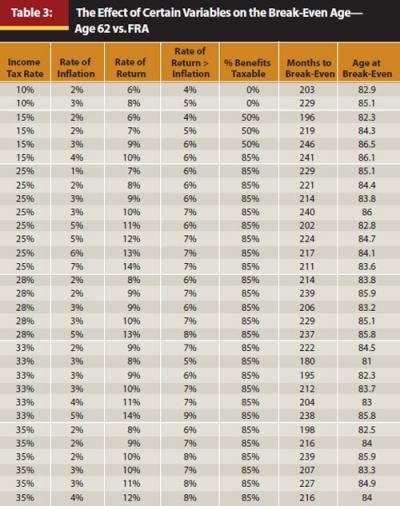

Table 3 provides an overview of how the variables we have discussed affect the break-even age for the worker in our example. We list various income tax rates, inflation rates, and rates of return on investment. In addition, we provide examples of different percentages of taxation of Social Security benefits. Up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits may be taxed, but this figure may be less depending upon overall income levels. Calculations were performed for each set of variables listed, and the break-even results are shown in Table 3.

The average mortality for a male and female who reach age 62 today is 83.2 and 85.5 respectively.7 In order to break even on or before average mortality, the rate of return on investment should exceed the rate of inflation by 4 percent to 6 percent at lower tax rates (and with lower percentages of Social Security benefits taxed). Other things being equal, this percentage needs to be higher as the marginal tax rate and/or the rate of inflation increases. In the medium tax brackets, the rate of return may need to exceed the rate of inflation by 6 percent to 8 percent, and in the higher tax brackets, the rate of return may need to be 7 percent to 9 percent (or more) above the rate of inflation.

Full Retirement Age vs. Age 70 Retirement

Workers are not required to start collecting benefits by the time they reach full retirement age. They receive delayed retirement credits by waiting to collect Social Security benefits as late as age 70. The amount of delayed retirement credit is 8 percent per year added to the PIA for each year beyond full retirement age, for anyone born in 1943 or later.

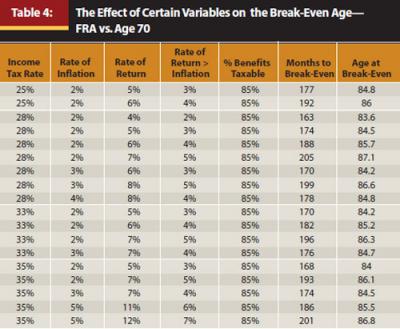

Continuing with our previous example, the same worker born March 2, 1949, is considering filing for benefits at age 66 or waiting until age 70 to collect the maximum number of delayed retirement credits. Table 4 illustrates the effects of inflation, taxes, and investment return on the break-even age. In this scenario break-even represents the number of months beyond age 70 when the two adjusted income streams are the same.

A male who will be 66 years old four years from today can expect to live on average an additional 18.2 years beyond age 66 or until age 84.2. Under similar circumstances, a female can expect to live on average an additional 20.3 years beyond age 66 or until age 86.3.8 Based on these statistics, the return on investment does not need to exceed inflation by as much as it did in our prior example. A male in the 28 percent tax bracket needs his return on investment to exceed inflation by about 3 percent when inflation is mild. The return on investment would need to be somewhat higher at higher marginal tax rates or when inflation is higher. The return on investment would also need to be higher for a woman because of average longer life span. To break even around age 86.3, the rate of return needs to exceed inflation by 4 percent to 5 percent when inflation is mild. At higher marginal tax rates and/or higher inflation rates, the rate of return may need to be 6 percent or more to break even by age 86. One might conclude that on average it is financially more beneficial for a woman to consider delaying Social Security benefits until age 70 than it is for a man.

Factors other than a break-even calculation may influence the decision to start benefits at age 70 rather than at FRA. Individuals in good health who expect to live well into their 80s may decide that filing for benefits at age 70 is a good deal. They spend down other assets while their Social Security “deferred annuity” grows at 8 percent per year with little or no risk. Others may wait until age 70 to collect benefits because they do not want to risk running out of money in their later years. Meyer and Reichenstein (2010) discuss the advantages of filing at age 70 to minimize longevity risk.

Multiple Entitlement

Up until now our examples have dealt with a single worker entitled to a retirement benefit. The choice of when to start collecting benefits becomes more complicated when other beneficiaries are entitled on the worker’s record or when the worker is entitled to more than one benefit. Family structures today can become quite complex given the high divorce rate, the rise of second families, children born out of marriage, and so on. Each new layer of family composition can change the financial advantages of when to start claiming benefits.

Although more complicated, break-even calculations in these situations have general similarities. Total benefits for one month of entitlement are compared with the benefits for another month of entitlement to determine a break-even age. Sometimes it is necessary to analyze two or more options before deciding when is the best time to begin collecting benefits.

Worker and Child

Generally speaking, children may collect benefits on the worker’s record until age 18. If a child is under age 16, the mother (father) of the child may also be entitled to benefits on the worker’s record. Each eligible family member is entitled to up to half of the worker’s PIA subject to a family maximum, which is generally between 150 percent and 180 percent of the PIA. By taking an earlier month of entitlement, a worker may gain from having a young child collect benefits on his/her account. This option may be precluded if the worker waits until full retirement age, because the child may be 18 or older by that time. Moreover, the child likely qualifies for favorable tax treatment on Social Security benefits if he/she has little or no other income.

Let us continue with our example of a worker born March 2, 1949, who is contemplating filing for Social Security at age 62 versus full retirement age. Assume the same input variables as above: a CPI of 3 percent, a marginal tax rate of 28 percent, and an after-tax rate of return of 3.6 percent. However, in this scenario his 14-year-old daughter, born August 1996, is entitled to a child’s benefit on his record in the amount of half of the PIA if he takes the earlier filing date. His daughter will receive 41 months of child’s benefits before turning 18 in August 2014. If the father waits until FRA to file for Social Security, his daughter will not be eligible for benefits. As a result, by claiming benefits at age 62 versus claiming at FRA, the break-even age is 275 months—nearly 23 years after he reaches full retirement age when he is almost 89 years old. In this situation, he should probably consider filing at age 62 instead of waiting until FRA or later.

Couples

Deciding when couples should start collecting benefits can become quite complex. In addition to the variables discussed before, Social Security law and regulations may permit one or both partners to file for spouse’s benefits depending upon the circumstances. Other variables may also influence the decision, including the variations in the ages of the couple, the working history of each partner, and the amount of each individual’s PIA. As a result of these and other factors, there are often multiple permutations for each couple’s particular situation.

A spouse may be entitled to the higher of the retirement benefit on his/her own record or half of the PIA actuarially reduced for age on the record of his/her spouse. A spouse who files for either retirement or spouse’s benefits before FRA is deemed filed for both benefits. That is, he/she cannot restrict the application to one type of benefit only. In effect, the spouse receives only the higher of the two benefit amounts. After a spouse reaches FRA, however, he/she can restrict the application to one type of benefit only. This means that he/she can file for one type of benefit at FRA and the other benefit later. One consequence of this flexibility is that a lower-earning spouse may file for retirement benefits at age 62, and the higher-earning spouse files for spousal benefits at FRA and switches to his/her own retirement benefit at age 70.

A worker may also file for benefits at FRA, suspend benefits until age 70, and then collect the maximum delayed retirement credits. This allows the worker’s spouse to collect spousal benefits on the worker’s record at FRA and subsequently file for his/her own retirement benefits at age 70, thereby also receiving maximum delayed retirement credits.

Every family’s situation is unique—a strategy that may be appropriate for one couple does not necessarily mean that it’s appropriate for another. However, break-even calculations may be constructed according to individual circumstances.

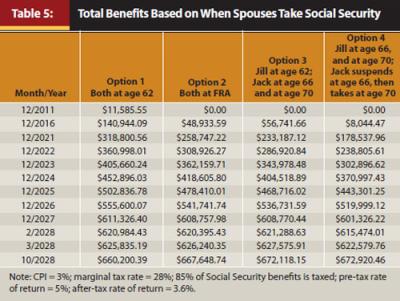

Consider a couple, Jack born on March 2, 1949, and Jill born on April 2, 1950. Jack’s PIA at age 62 is $2,000, and Jill’s PIA at age 62 is $1,200. Neither of them is working, so the work test does not apply. They do not need the money immediately and are flexible in when they start collecting benefits. They are considering four options: (Option 1) both start benefits at age 62, (Option 2) both start at FRA, (Option 3) Jill starts at age 62, and Jack files for spousal benefits at FRA and retirement benefits at age 70, (Option 4) Jack files for retirement benefits at FRA and suspends benefits until age 70, and Jill files for spousal benefits at FRA and retirement benefits at age 70. Assume a CPI of 3 percent, a marginal tax rate of 28 percent, and an after-tax rate of return of 3.6 percent.

Table 5 summarizes break-even calculations for each of these options. Total benefits are compared at the designated time frames, including break-even ages.

At the end of February 2028 total benefits for Option 3 exceed the total benefits for Options 1 and 2. Jack will be about 79 years old and Jill will be almost 78. Rather than both filing at age 62 or both filing at FRA, it would seem to be more advantageous for Jill to take benefits at age 62 and Jack to claim spousal benefits at FRA and switch to retirement benefits at age 70. By the end of October 2028, however, when Jack is still 79 years old, and his wife is 78, Option 4 becomes more advantageous than Option 3. The couple might seriously want to consider having Jack file at 66, suspend benefits, and collect his maximum possible benefit at age 70. This will allow Jill to receive spouse’s benefits on Jack’s account at FRA and file for her own retirement benefits at age 70. Fahlund (2010) reaches a similar conclusion in analyzing strategies for one hypothetical couple. Of course, results may vary depending on the values of the input variables discussed above (inflation, taxes, rate of return).

The Impact of the Worker’s Decision on Widow(er)’s Benefits

Any discussion of when to start collecting Social Security should address the effect of the worker’s decision on widow(er)’s benefits. A surviving spouse is generally limited to the benefit amount the worker received at the time of death. If the worker received a reduced benefit at the time of death, the widow(er)’s benefit cannot exceed the greater of this amount or 82.5 percent of the PIA. On the other hand, if the worker received delayed retirement credits at time of death, the widow receives this increased benefit amount. Of course, this increased amount may be actuarially reduced if the surviving spouse files for widow’s benefits prior to her own FRA.

This provision of the law has persuaded some researchers (for example, Munnell and Soto 2007) that men, who are usually the higher income earners, should claim benefits later than FRA in order to maximize benefits for their surviving spouses.

Retirement and Widow(er)’s Benefits

Unlike a spouse, a widow filing for benefits before FRA is not deemed filed for both retirement and widow’s benefits. In fact, in these situations, a widow will often file for one benefit prior to FRA and the other benefit later. Generally speaking, it is better to file for the lower benefit first and the higher benefit later (FRA or age 70). The issue is complicated by the fact that someone may be eligible for widow’s benefits as early as age 60 (age 50, if disabled), whereas to be eligible for retirement benefits you must be at least age 62. Moreover, a widow may be entitled to delayed retirement credits on her widow’s benefit if the deceased wage earner had been entitled to these credits prior to his death.

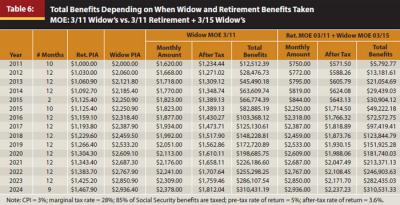

Consider a widow who qualifies for either retirement benefits or widow’s benefits in March 2011 when she turns 62. Her retirement PIA is $1,000 and the widow’s PIA is $2,000. The widow’s PIA is reduced by 19 percent at age 62.9 Should she take the higher benefit (widow’s) now, or the lower benefit (retirement) now and the higher (widow’s) benefit later?

As shown in Table 6, the advantage of taking the higher widow’s benefit first is somewhat offset by taking the lower retirement benefit instead. The net financial advantage at FRA is $35,870.27 ($66,774.39 minus $30,904.12). This amount is recovered within a little more than 9½ years. The break-even age is September 2024 when the widow is still only 75 years old. It would appear advantageous for her to take the lower retirement benefit at 62 and the higher widow’s benefit at full retirement age.

If we change this example so that the retirement PIA in 2011 is $1,700 instead of $1,000, it becomes more advantageous to file for widow’s benefits first and take the higher retirement benefit at 70. By waiting until age 70 to start collecting retirement benefits, the amount of the retirement benefit will be higher than the widow’s PIA because of delayed retirement credits she accumulates on her own record.

Conclusion

Deciding when to file for Social Security involves many factors. Break-even analysis provides planners a valuable tool to assist clients with this decision. Break-even calculations may be tailored to individual and family circumstances. They also accommodate economic variables such as inflation, return on investment, and current tax rates. If clients are flexible regarding when to start collecting benefits, conducting break-even calculations will allow them to make more informed decisions.

Endnotes

- For a chart on full retirement age by year of birth, refer to Social Security’s website: www.socialsecurity.gov/pubs/retirechart.htm.

- The calculation of the PIA can be found online in Social Security’s Program Operations Manual System (POMS): secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/subchapterlist!openview&

restricttocategory=03006. - Social Security’s Online Retirement Estimator: www.socialsecurity.gov/estimator.

- For most people, the earliest filing date is age 62 and 1 month. Generally speaking, a worker must be age 62 for the entire month before she can start collecting benefits. However, someone born on the 1st or 2nd of the month may qualify for benefits in the month of attaining age 62.

- A worker’s PIA is reduced by 5/9 of 1 percent per month for the first 36 months he elects benefits prior to FRA and by 5/12 of 1 percent per month thereafter. In performing the actual benefit calculations, the Social Security Administration rounds down both the PIA and the monthly benefit payment. The PIA is rounded down to the nearest dime, and the monthly benefit payment is rounded down to the nearest dollar.

- Social Security Administration. 2009. Annual Statistical Supplement, Table 5.B8. www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2009/5b.html.

- In this document we use Social Security’s Life Expectancy Calculator to determine average remaining life expectancy at designated ages. Information is based on its cohort life expectancy tables. For more information, see www.socialsecurity.gov/planners/lifeexpectancy.htm and www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/population/longevity.html. If periodic life tables are used instead of cohort life tables, average mortality may be somewhat lower.

- Social Security Benefits Planner, Life Expectancy: www.socialsecurity.gov/planners/lifeexpectancy.htm.

- Social Security POMs Section 00615.301, Reduced Widow(er)’s Benefits: secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0300615301.

References

Fahlund, Christine S. 2010. “5 Social Security Strategies for Couples.” Journal of Financial Planning (December).

Meyer, William, and William Reichenstein. 2010. “Social Security: When to Start Benefits and How to Minimize Longevity Risk.” Journal of Financial Planning (March).

Muksian, Robert. 2004. “The Effect of Retirement Under Social Security at Age 62.” Journal of Financial Planning (January).

Muksian, Robert. 2006. “Calculating Break-Even Ages for Delaying Social Security Beyond Normal Retirement Age.” Journal of Financial Planning (March).

Munnell, Alicia H., and Mauricio Soto. 2007. “When Should Women Claim Social Security Benefits?” Journal of Financial Planning (June).

Rose, Clarence C., and L. Keith Larimore. 2001. “Social Security Benefit Considerations in Early Retirement.” Journal of Financial Planning (June).