Journal of Financial Planning: December 2018

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is the founder of Goals Gap Planning LLC in Laguna Beach, Calif., and Las Vegas, Nev.

John Brannon, CFP®, CTP, is a portfolio adviser with Beshear Financial in Cincinnati, Ohio and a Ph.D. candidate with The American College of Financial Services.

In advance of the holiday and year-end giving season, this column reviews changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and suggests strategies for taxpayers who receive little or no tax benefit from their charitable giving.

Charitable Giving Changes

The TCJA made three major changes to the charitable contribution deduction. First, for cash contributions, the prior-law 50 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI) limitation on deductible charitable contributions for the current year increased to 60 percent of AGI from 2018 through 2025. For example, if Ann has AGI of $100,000 and makes a cash donation of $57,000 to her favorite charity, she can deduct the full amount in 2018. In 2017, her deduction would have been limited to $50,000 (50 percent x $100,000), with a $7,000 ($57,000 – $50,000) carryover to 2018 of the excess contribution.

Second, the TCJA repeals the charitable deduction for 80 percent of payments to an institution of higher education in exchange for the right to purchase seats at athletic events. So, if Frank donates $10,000 to his alma mater in exchange for the right to purchase two 50-yard line football season tickets that cost an additional $6,000, the allowable charitable deduction for the $10,000 payment in 2018 is $0, rather than the $8,000 (80 percent x $10,000) allowed under prior law. No deduction is allowed for the purchase of the tickets themselves either.

Third, for years after 2016, the TCJA repeals the provision relieving a donor of the contemporaneous written acknowledgement requirement for contributions of $250 or more if the charitable organization reported the required information to the IRS. Previously, there was an alternative, whereby charities were permitted to file a document with the IRS containing detailed information about the donor and his or her gift. This change should have limited practical effect, as most charities send acknowledgement letters to all donors for their contributions.

The Charitable Contribution/State Tax Credit Battle

Another major charitable planning change is a byproduct of the TCJA’s $10,000 limit on personal state and local taxes for the years 2018 through 2025. In May, New Jersey passed legislation allowing its taxpayers to make charitable contributions to designated organizations in exchange for reductions in their taxes. Prior to the TCJA, 33 states had similar deduction-for-credits programs in place.

The Treasury Department responded to this legislation with Proposed Regulation 1.170A-1(h), which provides for both newly created and pre-existing tax credit programs that a taxpayer who receives a state or local tax credit in exchange for a payment or transfer of property to a charity must reduce the charitable contribution deduction by the amount of the credit. In other words, if Alex makes a payment of $1,000 to a charity and receives a state tax credit of $700 (70 percent x $1,000) in consideration for the contributions, Alex’s charitable contribution deduction is reduced to $300 ($1,000 – $700).

Post-TCJA Charitable Contribution Strategies

Although tax savings is not the primary reason many taxpayers make charitable contributions, changes made by the TCJA may still have an adverse effect on charitable giving. Generally, to receive a tax deduction for charitable giving, an individual must itemize deductions. From 2018 through 2025, the Tax Policy Center projects nine out of 10 individuals will claim the standard deduction, thanks to the new $12,000 standard deduction ($18,000 for head-of-household filers and $24,000 for married couples filing jointly), the elimination of miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2 percent floor, and the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap of $10,000. In other words, only one out of 10 individuals will itemize deductions and receive tax deductions for charitable giving.

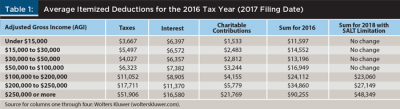

Table 1 gives an indication of itemized deduction patterns (the IRS does not break this data down by filing status). Also, Table 1 shows the averages for those who itemized and reported a number on Schedule A in the deduction category, not those who reported zeroes in a category or did not itemize.

With regard to charitable giving, itemizing deductions, and the averages from Table 1, four categories of individuals can be identified.

Category 1: Does Not Itemize

The first category is those who will claim the standard deduction (e.g., non-homeowners with less than $100K of AGI). Strategies include: (1) volunteering; (2) donating appreciated property; and (3) if over age 70½, making qualified charitable distributions from an IRA.

Example: Ann is a single, non-homeowner with $60,000 of AGI. She is in the 22 percent federal marginal income tax bracket, and she expects to claim the standard deduction; her only itemized deduction is $5,000 of state and local taxes, well below the $12,000 standard deduction amount.

Volunteering. Considering federal payroll (7.65 percent) and income (22 percent) taxes, to make a $1,000 charitable contribution, Ann must earn $1,421 ($1,000/(1 – (0.22 + .0765))) before tax. Consequently, Ann chooses to volunteer for a variety of causes.

Donating appreciated property. Ann contributes $1,500 annually to her church. She could receive a tax benefit by donating $1,500 of her mutual fund shares that are held in a brokerage account. The mutual fund shares have an income tax basis of $500. By transferring the mutual fund shares to the church, she can avoid recognizing the $1,000 gain ($1,500 – $500) and the $150 (15 percent x $1,000) in federal tax she would owe on the gain. Ann does not receive a deduction for the donation that an itemizer would, but at least she can avoid paying tax on the gain.

Making qualified charitable distributions from an IRA. If Ann is over age 70½, she could transfer $1,500 from her IRA directly to charity. The IRA distribution is not reported in her income, allowing Ann to satisfy her pledge obligation and receive a $330 (22 percent x $1,500) tax benefit, even though she does not itemize.

Category 2: On the Brink of Itemizing Deductions

The second category is those who would itemize if they doubled their charitable giving (e.g., taxpayers in the $100K to $200K range). Strategies include: all of those for category 1 individuals, plus: (1) bunching charitable contributions in one year, allowing them to itemize deductions in one year and claim the standard deduction in alternating years; and (2) taking advantage of donor advised funds.

Example: Barry is a head-of-household homeowner with $100,000 in AGI. Barry’s deductions are similar to the average itemized deductions from Table 1. He claims taxes of $6,323; interest expense of $7,382; and charitable contributions $3,244, for a sum of $16,949, meaning he will claim the $18,000 standard deduction rather than itemize.

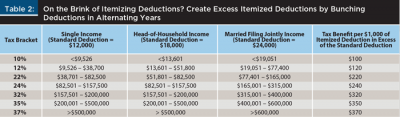

Bunching charitable contributions in 2018 and 2019. If Barry was so inclined and had the assets available to bunch his 2018 and 2019 charitable contributions in 2018, he could claim total itemized deductions of $20,193 ($16,949 + $3,244), $2,193 in excess of the $18,000 head-of-household standard deduction amount in 2018, and then claim the standard deduction in 2019. Alternatively, he could claim the standard deduction in 2018 and bunch charitable contributions at the beginning and end of 2019. In his 22 percent marginal federal tax bracket, this excess itemized deduction would reduce his federal taxes $482 (22 percent x $2,193) in 2018 and 2019. Other itemized deductions, such as medical expenses and tax payments, could also be bunched to increase the excess itemized deduction.

Table 2 illustrates the 2018 tax benefit for those on the brink of itemizing deductions who can create excess itemized deductions by bunching those deductions in alternating years.

Donor advised funds. The ideal technique for implementing this bunching strategy is a donor advised fund. Charitable organizations may not be thrilled with the alternating-year bunching strategy, but a contribution to a donor advised fund of the two-year total in the first year creates an immediate deduction of the two-year amount. The charitable distributions from the donor advised fund may then be spread over the two-year period. Research whether a donor advised fund is a suitable strategy for your client, as there are many pros and cons of using them, including investment minimums and fees.

Category 3: Would Not Itemize Without Charitable Contributions

The third category is itemizers who would not itemize without charitable contributions (e.g., taxpayers in the $200K to $250K range). Strategies include: all of the previous strategies with emphasis on planning not to itemize in one year and bunching charitable contributions into alternating years when they do itemize.

Category 4: Would Itemize Regardless of Charitable Contributions

The fourth category is those who would itemize regardless of charitable contributions (e.g., homeowners who have outstanding mortgages and higher taxable incomes). Strategies include: all of the previous strategies, plus traditional planning, such as charitable annuities, trusts, and entities.

Example for categories 3 and 4: Ed and Fran itemize every year. They are both 72 years old; married-filing-jointly homeowners with $450,000 in AGI. Their deductions are similar to the average itemized deductions in Table 1, except they paid off their mortgage in the previous year. They now claim: taxes of $51,906 (limited to $10,000 by the TCJA); interest expense of $0; and charitable contributions $21,769, for a sum of $31,769. With their mortgage paid off, they will itemize deductions but only because of their charitable giving.

They would be wise to contribute to their charities using qualified charitable distributions from IRAs or use donor advised funds to implement a bunching strategy. By doubling their contributions every other year and claiming the standard deduction in the off year, they would have excess deductions of $26,938 (($21,769 + $21,769 + $10,000) – ($24,000 + $1,300 + $1,300)), which at their 35 percent federal tax rate would provide tax savings every other year of $9,428 (35 percent x $26,938).

Summary

December is the peak month of the charitable giving season. For many donors, charitable donations will determine whether they itemize or claim the standard deduction in 2018 and 2019. Help your clients compare their projected itemized deductions to their standard deduction amounts to see which charitable giving technique would be most beneficial.