Journal of Financial Planning: December 2011

Betty Meredith, CFA, CFP®, CRC®, is director of education and research for the International Foundation for Retirement Education (InFRE). She participates in and incorporates research findings and best practices into InFRE’s Certified Retirement Counselor® certification study and professional continuing education programs to help professionals meet the retirement preparedness and income management needs of clients and employees.

I was somewhat surprised to receive an invitation from the Financial Planning Association (FPA) late last summer to participate in a conference call with representatives from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) on recommended retirement income solutions for American workers. I’ve pointed out several times in this column the need for our profession to establish more concrete guidelines around this issue.

The U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging asked the GAO to report1 on recommendations of professionals and choices made by American workers regarding retirement income. For this report, the GAO interviewed a variety of academics, financial professionals, and industry sources, along with officials from the Department of Labor, the Internal Revenue Service, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Social Security Administration, and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

Recommendations and Choices

The GAO randomly selected five scenarios from the National Institute on Aging’s Health and Retirement Study (HRS)2 in the lowest, middle, and highest quintiles with varying dependence on defined-benefit and defined-contribution assets. Those interviewed were asked to recommend retirement income solutions for near-retirement workers, ranging from a single individual below the poverty level to a millionaire married couple. Delaying Social Security and increasing annuitized income tied as the solutions most often recommended by professionals.

The GAO study also identified retirement income choices being made by retirees today:

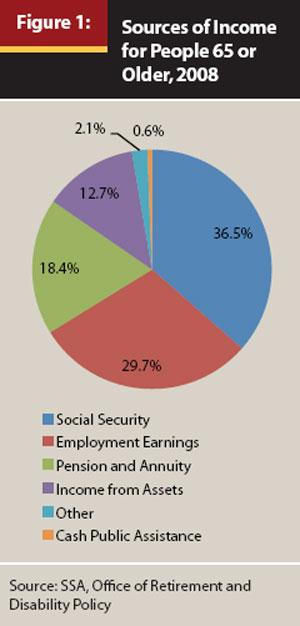

- Individuals over age 65 are depending on employment income for almost one-third of their income. Average sources of aggregate retirement income for individuals over age 65 are shown in Figure 1.3 The average 401(k) plan balance for workers in their 60s, with at least 30 years of job tenure at their current employer, was about $200,0004 at year-end 2009; Figure 1 shows that income from assets produces less than 13 percent of total income. This substantial dependence on employment income is concerning if not properly protected; it increases the risk of retirement income failure if the health of the retiree or spouse precludes them from working.

- People are choosing not to delay Social Security. Social Security is the most cost-effective, inflation-adjusted option for increasing lifetime retirement income, as it is probably the world’s least expensive annuity. Today, 43 percent of people take their benefit within one month of their 62nd birthday.5 About 73 percent take benefits before age 65, which means they get penalized $1 for every $2 of income earned over the 2011 earnings limit of $14,160. Only 14 percent take benefits the month they reach their full retirement age, and 3 percent begin after their 66th birthday. If health allows, delaying receipt of Social Security until age 70 1/2 will increase lifetime income for the primary earner and the spouse/survivor about 75 percent6 more than if they collected benefits at age 62.

- People over age 60 are decreasing their exposure to equities in their retirement portfolios. The allocation to equities for 401(k) holders in their 60s has steadily declined from 2005–2009. About 30 percent now have less than 20 percent in equities, and 42 percent have less than 40 percent in equities. A key principle for the success of a 4 percent systematic withdrawal plan is that equity exposure be at least 50 percent of assets7 for the portfolio to have a high probability of lasting at least 30 years. These individuals are trading future inflation and longevity protection for principal protection today, and need to be educated about protecting their retirement income and assets from other retirement risks as well.

The Need for Advice

The results of the GAO study clearly indicate the urgent need for better retirement income decisions by people who are over age 60. Just to give you perspective on the enormity of this issue, the total U.S. retirement market now consists of $18.2 trillion in assets,8 more than the $13.6 trillion in banking deposits in FDIC-insured U.S. banks and savings and loans, and more than current GDP. IRA assets at $4.9 trillion are the largest slice, and growing every year. The majority of IRA assets come out of employer defined-contribution plans, which now contain $4.7 trillion. Currently, most of the owners of these savings receive insufficient guidance on how to make informed decisions about when and how to convert their savings into retirement income. It’s a huge amount of capital, critical to the underlying financial stability of our country. Poor decisions will eventually affect everyone—not only the retiree—as the effects of the decisions “potentially place a heavier burden on public-need-based assistance and other resources.”9

What FPA Is Doing

FPA is currently working with the Society of Actuaries (SOA) Post-Retirement Needs and Risks Committee and the International Foundation for Retirement Education (InFRE) to build on work begun by SOA10 to more formally define retirement income best practice solutions and standards for middle mass and mass affluent consumers. Here are some questions we’re seeking to answer:

- What are planners doing to serve this market? What issues do they have in serving the market? Are there some changes that would enable them to serve the market better and more cost effectively?

- How do they set goals with this market?

- What is the process used for looking at risk, for minimizing taxes, and for setting a strategy for the distribution period?

- How should housing and housing equity be considered in financial/retirement planning?

- How does long-term care financing fit in?

- What would advisers recommend if they were free from policy constraints?

- What types of products would help advisers serve their clients?

- How do advisers engage in life issues such as helping clients think about what they need to do to get re-employed?

Conversations around these issues are tentatively being planned for the FPA Retreat 2012 conference next May. If the mid-market is a substantial part of your current or prospective business, stay tuned!

Endnotes

- United States Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). 2011. Retirement Income: Ensuring Income Throughout Retirement Requires Difficult Choices. Report to the Chairman, Special Committee on Aging, U.S. Senate (June).

- National Institute on Aging. 2007. Growing Older in America: The Health and Retirement Study. www.nia.nih.gov/ResearchInformation/ExtramuralPrograms/BehavioralAndSocial

Research/HRS.htm - Data reported by the Social Security Administration for pension income include regular payments from IRA, Keogh, or 401(k) plans. Non-regular (non-annuitized or lump sum) withdrawals from IRA, Keogh, and 401(k) plans are not included. “Other” includes non-cash benefits, veteran’s benefits, unemployment compensation, workers’ compensation, and personal contributions. Income from others is excluded.

- Investment Company Institute (ICI). 2011. 2011 Investment Company Fact Book. 51st ed.

- U.S. GAO ibid.

- Social Security Calculator, http://www.ssa.gov/: FRA 2011 benefits for a 66-year-old with $44,500 annual income.

- Bengen, William P. 1996. “Asset Allocation for a Lifetime.” Journal of Financial Planning (August).

- ICI ibid.

- U.S. GAO ibid.

- Society of Actuaries. 2010. Segmenting the Middle Market: Retirement Risks and Solutions, Phase II Report.