Journal of Financial Planning: April 2018

Sonya Britt-Lutter, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Her research in financial counseling, planning, and therapy utilizes her educational background in marriage and family therapy and financial planning from Kansas State University and Texas Tech University.

Cassandra Dorius, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of human development and family studies at Iowa State University. Her research on family instability and the well-being of individuals across behavioral, health, and financial domains is grounded in demographic and sociological training from Pennsylvania State University and the University of Michigan.

Derek Lawson, CFP®, is a doctoral student in personal financial planning at Kansas State University. His research is practitioner focused, allowing him to combine his past and present experience as a financial planner with his research interests.

Editor’s note: This research was presented at the 2017 FPA Annual Conference as unpublished research, where it received the award from the Journal of Financial Planning and the Financial Planning Association for the best theoretical research presented at the 2017 conference.

Executive Summary

- Cohabitation is a common path to marriage for many millennials, with two-thirds of couples living with a significant other at least once before marriage.

- By delaying or opting out of marriage in early years, couples may be less financially prepared for retirement in later years.

- Previous research has found that men and women who have consumer debt are more likely to begin cohabitating with their significant other, yet combining consumer debt is associated with a higher risk of relationship dissolution. In contrast, buying a home with one’s partner was associated in this study with a higher likelihood of transitioning to marriage, likely because of the higher entry and exit costs of the purchase.

- This study’s findings indicate that cohabiters have lower net worth and financial asset accumulation than married respondents, but repeat cohabiters and married respondents with previous cohabiting unions have no less non-financial assets than married respondents who have never cohabited.

- Younger clients who have cohabited many times may be less interested in long-term planning and more interested in current consumption in the form of non-financial assets; whereas clients who are not cohabiting or cohabiting for the first time with a long-term partner might be more future-oriented with their financial planning.

Cohabitation—or living with a significant other outside of marriage—is the most common way young adults form their first residential relationship in America today (Manning, Brown, and Payne 2014). Although fewer cohabiting couples are transitioning to marriage than in the past (Guzzo 2014), nearly two-thirds of marriages formed since the early 2000s involve couples who lived together prior to their wedding (Manning and Cohen 2012). Consequently, cohabitation is viewed by young adults as both a pathway toward, and an alternative to, marriage.

Often, the decision to begin cohabiting is not a formal one, but occurs gradually and without clear communication between partners on what it might mean to live together (Manning and Smock 2005). People frequently choose to cohabit so that they can spend more time together, because it is convenient for them to do so, and because it is a way to test the relationship (Rhoades, Stanley, and Markman 2009).

Like marriage, cohabiting unions provide adults an opportunity to live in a committed relationship, pool resources, establish economies of scale, and potentially work toward a shared financial future (Lundberg and Pollak 2014; Sassler 2004). Unlike married adults, cohabiters are prone to more frequent and earlier disruptions, are less likely to have shared children (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Curtin, and Mathews 2015), are less likely to own a home (Kerr, Moyser, and Beaujot 2006), and are more economically disadvantaged (Guzzo 2014), all of which may impact the level and quality of consumption and asset accumulation.

Although married and cohabiting couples are equally capable of establishing joint accounts to pay for shared expenses, the legal guidelines regarding the dividing of assets can be challenging for unmarried couples. This may negatively influence cohabitating partners’ willingness to invest in long-term asset accumulation, such as the purchase of a home and saving financial assets for retirement.

What relationships signify to others has changed over time. Work by Arnett (2000) demonstrated that in prior generations, early marriage and childbearing were cornerstones to being viewed as adults, but among millennials, career-oriented objectives like work and higher education are more central to being viewed as an adult.

Financial responsibility has been cited as one of the primary markers that influence young adults’ sense of feeling of being in-between adolescence and adulthood (Beutler 2012). During this developmental stage, young adults are, for what is likely the first time in their lives, starting to earn money and take on financial responsibility while simultaneously determining how to form their first residential relationship (Arnett 2000). What is more, many young adults today have taken on debt, which may be a reason for the increased cohabitation rates and delays in marriage (Addo 2014).

This study explores how living together outside of marriage influences net worth and the accumulation of financial and non-financial assets across the span of young adulthood.

Conceptual Background and Related Research

From an economic perspective, the decision to marry is based on perceived benefits and realized gains. People who expect to gain more from marriage than remaining single will marry. If the variation in expected versus realized gains are too great (i.e., less than anticipated), the relationship will dissolve (Becker 1981). When Becker wrote his theory, cohabitation was uncommon and socially unsanctioned. Individuals expected marriage to bring economics of scale and household-labor market specialization, and it was generally assumed that the husband would specialize in labor-market participation while the wife would specialize in household production (Lundberg, Pollak, and Stearns 2016). The family structures studied in Becker’s work focused on single or married adults, so further exploration is needed regarding whether cohabitation serves as a substitute for marriage in regard to investments in joint financial efforts. As society has changed, the perceived gains from marriage (and hypothetically cohabiting unions) have shifted from household-labor market specialization to shared leisure time (Lundberg et al. 2016).

To increase realized gains, individuals can engage in spousal-specific investments—a known contributor to increased relationship satisfaction (Britt and Huston 2012). In a practical sense, this means that people are putting time, energy, money, and other resources into a relationship that cannot easily be transferred to a new relationship. If an individual expected to gain 100 utils (a measure of utility or satisfaction) by being involved with a significant other, but invested time into the relationship so they actually receive 150 utils, that person is more likely to report a high degree of satisfaction that cannot be easily transferred to a new relationship, because new unions start at the original expectation of 100 utils of satisfaction.

Like married people, cohabiters also make partner-specific investments, although it may be more difficult to invest in these relationships for legal or other reasons. For example, less risk is associated with making investments of time and energy into a marriage where exit costs are greater and dissolution is less likely (Matouschek and Rasul 2008). According to NOLO data, the average divorce costs approximately $15,500 and takes about 10.7 months to complete (Michon 2014).

From a financial perspective, spousal-specific investments are potentially riskier for cohabiting versus married individuals (e.g., automatic co-ownership of assets obtained during cohabitation may not be the same as for marriage). In most states, for example, a boat purchased by a married person is owned 50 percent by each spouse regardless of contribution, whereas a boat purchased by a cohabitating person is owned by the person who made the contribution. At the dissolution of the relationship, separating assets can be more difficult for cohabiters. For individuals in a cohabiting relationship who have a clear separation plan, there is greater motivation to accumulate non-financial assets.

It is well-known that married respondents accumulate the greatest wealth over time measured by both financial assets and housing (Zissimopoulos, Karney, and Rauer 2015). By delaying or opting out of marriage in early years, couples may be allocating resources in a way that hinders long-term asset accumulation leading to lower retirement preparedness. That said, young couples who are planning to get married are more likely to start combining assets and debt prior to marriage (Addo 2017), which may cut down on some of the costs associated with lower wealth accumulation among single and cohabiting individuals.

Like trends of cohabitation among generations (Manning, Smock, Dorius, and Cooksey 2014), wealth also tends to follow patterns that are similar to one’s parents (Adermon, Lindahl, and Waldenström 2016). Prior research suggests that more than one-third (37 percent) of wealth is persistent across generations, net of bequests, and this may be due to children mimicking their parents’ savings behaviors (Charles and Hurst 2003). To explore whether this association is due to genetics or environment, Black, Devereux, Lundborg, and Majlesi (2015) investigated the differences in wealth between adopted children and their adoptive parents versus that of their biological parents. They found that the resulting wealth of the adopted children was much more closely related to that of their adoptive parents, indicating that the wealth environment one grows up in has a larger role in one’s own personal wealth accumulation than does genetic makeup. In consideration of wealth transfers influencing financial and non-financial asset accumulation, parental wealth during the formative years was included in this study as a control variable in the regression analyses.

Purpose

Understanding how young people are accumulating assets is important for long-term financial security and stability. The current study explored the financial implications of cohabitation among a younger cohort of individuals born between 1980 and 1984 at the cusp of the transition from the Generation X to the millennial era. Much of the prior literature has focused on older adults and the accumulation of financial assets and/or housing wealth, but more work is needed to understand the financial implications of relationship experiences among young adults who are setting the course for their long-term financial and relationship pathways.

The current study incorporated measures of net worth (total assets minus total debts), financial assets (including one’s primary residence, cash, stocks, mutual funds, etc.), and non-financial assets (such as cars, boats, furniture, and real estate other than the primary residence) to underscore the varied ways in which these family groupings may influence financial well-being.

When financial planners meet with prospective clients, it will be useful to learn about their relationship status to guide the conversation about what types of assets they have and how they are titled. Based on economic theory and related literature, the hypothesis to be tested as it relates to asset accumulation among millennial-aged respondents is:

H1: Married respondents will accumulate greater net worth, financial assets, and non-financial assets than other household types.

Data and Sample Characteristics

Data were obtained from the latest round of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 cohort (NLSY97). Respondents were between the ages of 12 and 17 when they were first interviewed in 1997 (N = 8,984). The most recent round of data was collected in 2013–2014 when respondents were between the ages of 28 and 34. The analytic sample relied on young adults aged 30 or older who responded to at least one financial well-being measure and the relationship assessment (N = 5,191).

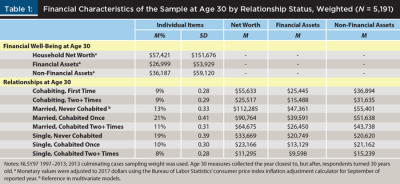

The NLSY97 includes household asset data when respondents turn 30 years old (see Table 1 for summary statistics for the current sample). Respondents were assumed to be out of college by this time and in the stage in life where they are taking on greater personal and career responsibilities, including transitioning to marriage, cohabiting, or remaining single.

The mean household net worth of the sample was $57,421 (SD = $151,676), mean financial assets were $26,999 (SD = $53,929), and mean non-financial assets were $36,187 (SD = $59,120). All reported monetary values were inflation-adjusted to 2017 dollars using the Consumer Price Index in September of the year the data were reported.

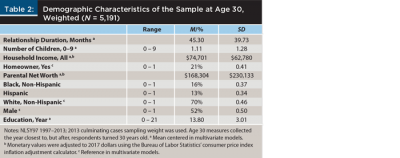

Among the sample, 45 percent were married, 18 percent were cohabitating (i.e., living with a partner in a marriage-like relationship), and 37 percent were unmarried and not cohabitating. Respondents had an average of 1.1 children (SD = 1.3). Mean household income was $74,701 (SD = $62,780), and 21 percent of respondents were homeowners. To control for possible distributions of wealth between generations, parental net worth, as reported by the parent when the respondent entered the survey in 1997, was used (M = $168,304; SD = $230,133). See Table 2 for a summary of demographic characteristics.

Analysis

Three ordinary least squares regressions were used to explore the financial implications of cohabitation. Marital and cohabitation experiences up to the age of 30 were used to predict net worth, financial asset, and non-financial asset accumulation of 30-year-olds. Due to missing data concerns, particularly with respect to the income-related questions, multivariate normal imputations were conducted with 50 imputations of the dataset (Graham, Olchowski and Gilreath 2007).

Results

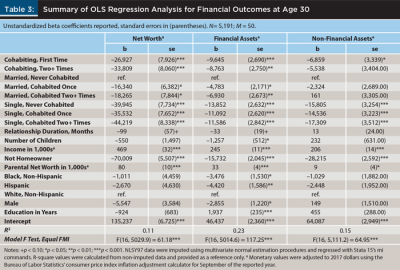

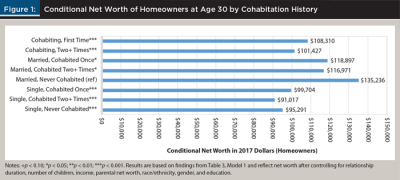

Net worth. The results of the multivariate regression analyses are presented in Table 3. As hypothesized, those with the highest net worth were the married respondents. Within the married group, respondents who had never cohabited had, on average, $16,340 more wealth than married respondents who had cohabitated once before, and $18,265 more wealth than married respondents who had cohabitated two times or more.

First-time cohabiters were the next wealthiest group; when compared to married, never-cohabited respondents, they had $26,927 less in wealth. Serial cohabiters had $33,809 less in wealth than respondents who were married and never cohabited.

The results indicate that single respondents had the least amount of net worth. Specifically, when compared to married, never cohabited people, single respondents who had never cohabited had $39,945 less in net worth, while single respondents who had cohabited one time had $35,532 less wealth, and single respondents who were serial cohabiters had $44,219 less net worth than respondents who were married and had never cohabited.

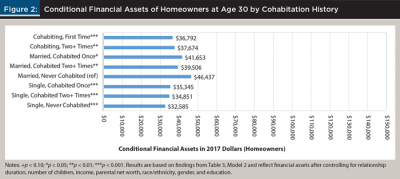

Financial assets. With respect to financial assets, married respondents who had never cohabited accrued the largest amount of financial assets. Specifically among married respondents, when compared to married, never-cohabited respondents, those who had cohabited one time had $4,783 less in financial assets, while respondents who were serial cohabiters had $6,930 less in financial assets. Respondents who were currently cohabiting for their first time held $9,645 less in financial assets as compared to their married, never-cohabited counterparts, while serial cohabiters had $8,763 less in financial assets.

Again, single respondents appeared to be the group with the least amount of financial assets, as single respondents who had never cohabited had $13,852 less in financial assets when compared to their married, never-cohabited counterparts. Single respondents who had cohabited held $11,092 or $11,586 less in financial assets if they cohabited one time or were serial cohabiters, respectively, as compared to married respondents who had never cohabited.

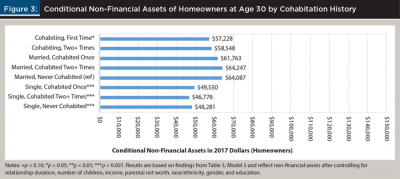

Non-financial assets. In terms of non-financial assets, results showed no difference in non-financial asset values among married respondents, regardless of how many times they had cohabited. First-time cohabiters reported $6,859 less non-financial assets as compared to married respondents, while serial cohabiters reported statistically no less in non-financial assets as compared to married respondents.

Once again, single respondents appeared to have less non-financial assets. When compared to respondents who were married and had never cohabited, single people had accrued $15,805 less in non-financial assets, while respondents who had cohabited one time had reported $14,536 less non-financial assets, and single people who were serial cohabiters had $17,309 less in non-financial assets. In summary, relative to married respondents, both cohabiting respondents and single respondents had less net worth, financial assets, and non-financial assets (see Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Control variables. Among the control variables, income and parental wealth were associated with an increase in net worth and asset accumulation. Not being a homeowner decreased net worth by about $70,009, financial assets by $15,732, and non-financial assets by $28,215.

Black, non-Hispanic, and Hispanic respondents were associated with lower financial assets as compared to white, non-Hispanic respondents, as were males compared to females.

A respondent’s number of years of education was positively associated with financial assets, and a statistically significant reduction in financial assets of $1,257 was found when children were present in the home.

Research Limitations

Certain limitations must be considered before taking financial planning implications into account—namely, issues of endogeneity. It is possible that causality may run contrary to the hypothesized relationship. For instance, perhaps cohabiting status does not lead to financial and non-financial asset accumulation as much as assets inform cohabiting status.

Furthermore, cohabiting individuals who were previously married and divorced may have different motivations with their assets. Future studies would benefit from continuing to explore the relationship of specific forms of assets and debts as it relates to relationship status. Furthermore, findings are only generalizable to samples of similar composition to the one used in this study.

Discussion

In light of the limitations, two-thirds of the respondents in the nationally representative sample lived with a partner outside of marriage by the time they turned 30, reinforcing prior literature that cohabitation has become a normative experience for young adults (Manning, Smock, Dorius, and Cooksey 2014). This study found significant support for the hypothesis that married respondents accumulate more wealth and financial and non-financial assets than other household types. And prior research was extended with findings that cohabiters were more likely to prefer the accumulation of non-financial assets as compared to financial assets. This is especially relevant to financial planners who are more focused on financial asset accumulation to help meet long-term financial goals versus current consumption in the form of non-financial assets.

Client intake questionnaires that do not ask about relationship statuses beyond the typical single, married, divorced, or widowed categories could be missing an opportunity for discussion of financial planning implications associated with cohabitation. Regardless of belief systems, cohabitation is becoming the norm and something that must be factored into the financial planning process.

Individuals who ever cohabited, regardless of current relationship status, had significantly lower net worth and financial assets than those who had married directly without cohabiting. The results for non-financial assets were mixed, with those who had cohabited two or more times looking most like currently married respondents, controlling for income, home ownership, number of children, parental net worth, and race. More work is needed to explore why respondents who had cohabited two or more times looked most similar to married respondents in regard to their non-financial assets, and to single respondents in regard to wealth and financial assets.

Those who were married and never cohabited or cohabited just once had significantly more financial assets, non-financial assets, and net worth as compared to their non-married, non-cohabiting counterparts (results not shown with alternate reference groups). This may be an indication of positive financial behaviors such as the need to save for the future while also balancing the couples’ need for home-use assets such as furniture.

Financial Planning Implications

Although young adults may not be the typical demographic for many financial professionals today, this trend is changing. As such, the results of this study have implications that are paramount for financial planners for several reasons. First, the transition of assets is occurring and many planners are wanting to continue to work with the children of their current clients. Knowing that many of these young clients are cohabiting with a significant other (or have done so in the past), and understanding how those decisions influence their financial and non-financial assets is important knowledge for the financial planner.

Second, this study offers support that the traditional view of marriage is not sufficient for understanding the needs of today’s young couples; cohabitation is common and it has unique impacts on financial well-being. For each additional cohabiting union from none to two or more, financial asset accumulation falls.

Future studies should consider following respondents over a longer period to identify the financial asset accumulation pattern past three cohabiting unions. All household types (single, cohabiting, and married with former cohabitations) reported less financial assets than married never-cohabited respondents. However, only single and first-time cohabiting respondents reported significantly less non-financial assets than married respondents. In other words, married respondents with prior cohabiting unions and respondents who were cohabiting for the second or more time had no less non-financial assets than married never-cohabited respondents. It could be the case that cohabiters have the desire to accumulate new household furnishings with each cohabiting union. The merging of two lives into one household naturally brings change. The desire to merge preferences may show through as purchasing different living room furniture, new artwork, etc. It could also be the case that different forms of transportation are needed with different cohabiting unions, and non-financial assets may have been purchased on credit.

When advising cohabiting clients, it will be important to take a closer look at non-financial asset accumulation and provide education regarding the life expectancy and depreciation of such items versus financial assets.

Financial planners can use the results of this study to better understand their clients’ mentality around the relationship. For example, working with younger clients who have cohabited many times may indicate that these individuals might be less interested in long-term planning and more interested in current consumption in the form of non-financial assets. Clients who are not cohabiting or cohabiting for the first time with a long-term partner could be focused on their long-term future together.

Financial planners should be sure to have in-depth discussions with clients about their relationship status, views around cohabiting, and long-term goals, both personally and professionally. These future-oriented conversations might also help clients think about the importance of saving financial assets, even if they do not have joint assets with their significant other. A client who has cohabited just once in their life, or who maybe are cohabiting for their first time, may not have significant financial consequences, but clients who are frequently cohabiting with significant others may be a sign that a discussion is warranted around the negative impact of such decisions on their financial assets and overall net worth.

References

Addo, Fenaba R. 2014. “Debt, Cohabitation, and Marriage in Young Adulthood.” Demography 51 (5): 1,677–1,701.

Addo, Fenaba, R. 2017. “Financial Integration and Relationship Transitions of Young Adult Cohabiters.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 38 (1): 84–99.

Adermon, Adrian, Mikael Lindahl, and Daniel Waldenström. 2016. “Intergenerational Wealth Mobility and the Role of Inheritance: Evidence from Multiple Generations.” IZA Discussion Papers No. 10126: 1–56. Available at hdl.handle.net/10419/145260.

Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Twenties.” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469–480.

Becker, Gary S. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Beutler, Ivan F. 2012. “Connections to Economic Prosperity: Money Aspirations from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 23 (1): 17–32.

Black, Sandra E., Paul J. Devereux, Petter Lundborg, and Kaveh Majlesi. 2015. “Poor Little Rich Kids? The Determinants of the Intergenerational Transmission of Wealth”. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 9227: 1–38. Available at hdl.handle.net/10419/114088.

Britt, Sonya L., and Sandra J. Huston. 2012. “The Role of Money Arguments in Marriage.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 33 (4): 464–476.

Charles, Kerwin K., and Erik Hurst. 2003. “The Correlation of Wealth across Generations.” Journal of Political Economy 111 (6): 1,155–1,182.

Graham, John W., Allison E. Olchowski, and Tamika Gilreath. 2007. “How Many Imputations Are Really Needed? Some Practical Clarifications of Multiple Imputation Theory.” Prevention Science 8 (3): 206–213.

Guzzo, Karen B. 2014. “Trends in Cohabitation Outcomes: Compositional Changes and Engagement Among Never-Married Young Adults.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76 (4): 826–842.

Kerr, Don, Melissa Moyser, and Roderic Beaujot. 2006. “Marriage and Cohabitation: Demographic and Socioeconomic Differences in Quebec and Canada.” Canadian Studies in Population 33 (1): 83–117.

Lundberg, Shelly, and Robert A. Pollak. 2014. “Cohabitation and the Uneven Retreat from Marriage in the United States, 1950–2010.” In Human Capital in History: The American Record, 241–272. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at ideas.repec.org/h/nbr/nberch/12896.html.

Lundberg, Shelly, Robert A. Pollak, and Jenna Stearns. 2016. “Family Inequality: Diverging Patterns in Marriage, Cohabitation, and Childbearing.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (2): 79–102.

Manning, Wendy D., and Pamela J. Smock. 2005. “Measuring and Modeling Cohabitation: New Perspectives from Qualitative Data.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67 (4): 989–1,002.

Manning, Wendy D., and Jessica A. Cohen. 2012. “Premarital Cohabitation and Marital Dissolution: An Examination of Recent Marriages.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (2): 377–387.

Manning, Wendy D., Susan L. Brown, and Krista K. Payne. 2014. “Two Decades of Stability and Change in Age at First Union Formation.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76 (2): 247–260.

Manning, Wendy D., Pamela J. Smock, Cassandra Dorius, and Elizabeth Cooksey. 2014. “Cohabitation Expectations Among Young Adults in the United States: Do They Match Behavior?” Population Research and Policy Review 33 (2): 287–305.

Martin, Joyce A., Brady E. Hamilton, Michelle J. K. Osterman, Sally C. Curtin, and T. J. Mathews. 2015. “Births: Final Data for 2013.” National Vital Statistics Reports 64 (1). National Center for Health Statistics. Available at cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf.

Matouschek, Niko, and Imran Rasul. 2008. “The Economics of the Marriage Contract: Theories and Evidence.” The Journal of Law and Economics 51 (1): 59–110.

Michon, Kathleen. 2014. “How Much Will My Divorce Cost and How Long Will It Take?” NOLO.com, available at nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/ctp/cost-of-divorce.html.

Rhoades, Galena K., Scott M. Stanley, and Howard J. Markman. 2009. “Couples’ Reasons for Cohabitation: Associations with Individual Well-Being and Relationship Quality.” Journal of Family Issues 30 (2): 233–258.

Sassler, Sharon. 2004. “The Process of Entering into Cohabiting Unions.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (2): 491–505.

Zissimopoulos, Julie M., Benjamin R. Karney, and Amy J. Rauer. 2015. “Marriage and Economic Well-Being at Older Ages.” Review of Economics of the Household 13 (1): 1–35.

Citation

Britt-Lutter, Sonya, Cassandra Dorius, and Derek Lawson. 2018. “The Financial Implications of Cohabitation Among Young Adults.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (4): 38–45.