Journal of Financial Planning: January 2026

Christopher D. Bentley, CLU, BFA, CRPC, is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® and former wealth management adviser with 15 years at RBC and Ameriprise. A Naval Academy graduate and M.B.A. holder, he founded Wings for Widows (www.wingsforwidows.org) in 2018. Chris authored The Widow’s Guidebook to Financial Wellness and advocates nationally for the widowed community.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

When a client loses a spouse, a planner’s immediate focus is prudently on triage: securing cash flow, addressing housing, and providing a steady hand amidst emotional turmoil. In this hierarchy of needs, long-term goals like college planning can feel like an impossible luxury, a conversation for a distant and unimaginable future. Framing this conversation not as an added burden, but as a beacon of hope, is one of the most powerful ways a planner can serve a grieving family. Proactively guiding a client through this landscape demonstrates foresight and a profound commitment to their family’s future. By understanding the seismic shifts brought about by the FAFSA Simplification Act and applying specific strategies tailored to the client’s new reality, planners can turn attending college from an improbability back into a tangible reality.

Assessing the New Financial Reality

The first step is to move beyond immediate crisis management to establish a new financial snapshot. This is not just about updating the balance sheet but about creating a forward-looking cash flow projection that accounts for the new dynamics of the household. The planner must ask: How has income changed, factoring in lost salary, Social Security survivor benefits, and the surviving spouse’s potential return to the workforce? How has the balance sheet shifted with the infusion of life insurance proceeds or the assumption of new liabilities?

Based on this new reality, we can segment clients into three broad scenarios that will guide our subsequent discussions:

- Scenario A: “Stay the course.” The surviving spouse was the primary earner, or life insurance and other assets are sufficient to maintain the existing college plan with only minor adjustments.

- Scenario B: “Recalibrate.” The deceased spouse was the primary earner, creating a significant income gap. The goal remains achievable, but the path must change significantly.

- Scenario C: “Rebuild.” The loss creates severe financial hardship, requiring a fundamental rethinking of the entire college-funding strategy.

Planning Considerations for College Aid

Planners must be familiar with the significant changes introduced by the FAFSA Simplification Act. For your clients, these new rules create both substantial opportunities and potential pitfalls.

From EFC to Student Aid Index (SAI). The misleading term “Expected Family Contribution” (EFC) has been replaced by the SAI. This is more than semantics; it reframes the metric as an eligibility index for aid, not a bill for college. Crucially, the SAI can be a negative number, with a floor of –$1,500. This allows financial aid administrators to better distinguish between families with no ability to pay (a $0 SAI) and those with significant unmet basic needs (a negative SAI).

Understanding cost of attendance (COA). Each college publishes a cost of attendance—its official estimate for one academic year. This COA is the maximum amount of total financial aid a student can receive. It includes direct costs (tuition, fees, on-campus room and board) and indirect costs (books, supplies, transportation, personal expenses, and housing allowances).

Here’s where clients get confused: the housing component is a standardized allowance based on whether students live on-campus, off-campus, or at home. It’s not reimbursement of actual rent.

The fundamental formula is simple: COA – SAI = Financial Need.

This means reducing the COA is just as meaningful as reducing the SAI.

FAFSA Simplification’s Key Impacts for Widowed Clients

A positive change for widows and any single parent is the new formula includes a more generous income-protection allowance (IPA), shielding more of a parent’s income from the calculation. Furthermore, Pell Grant eligibility has been expanded and is now directly tied to the federal poverty level. For a single parent, the income thresholds are particularly favorable. If their adjusted gross income (AGI) is at or below 225 percent of the poverty level for their family size, they automatically qualify for the maximum Pell Grant.

The single most detrimental change for some families is the elimination of the “multi-child discount.” Previously, the parent’s contribution was divided by the number of children in college. The SAI formula removes this provision entirely, which can dramatically reduce or eliminate need-based aid for families with multiple children enrolled simultaneously.

Tax Filing Status Matters

A client’s tax filing status is a key lever in managing the AGI that drives the SAI calculation. Planners should work with a client’s tax professional to ensure they’re using the most advantageous status:

- Married filing jointly: In the year of the spouse’s death.

- Qualifying surviving spouse: For two years after, if they have a dependent child, allowing them to use the favorable joint return tax rates.

- Head of household: In subsequent years, this is still more advantageous than filing single.

Higher deductions mean lower taxes, and lower taxes result in lower SAI calculations and a higher financial need.

The Two-Step FAFSA Process

For a recently widowed parent, the FAFSA’s reliance on prior-prior year tax data presents a (correctible) issue. The automated data will pull from a joint tax return that reflects a financial reality that no longer exists. Overcoming this requires two distinct but necessary actions; let’s review for the 2024–2025 cycle:

- Correct the FAFSA. First, the parent must report their marital status as “Widowed” (as of the day they file the FAFSA). Then, they must manually subtract the deceased spouse’s 2022 income and earnings from the figures imported from the joint tax return.

- Initiate the professional judgment review. After submitting the corrected FAFSA, the essential second step is to initiate a “special circumstances” or “professional judgment” (PJ) review with each college’s financial aid office. This formal process allows administrators to adjust the FAFSA data to reflect the family’s current, lower-income reality.

Because this is a manual process handled differently by each school, proactive and persistent follow-up is critical to ensure the review is completed promptly.

Planner Guidance Dependent on Client Timeline

Applying these new rules requires a tailored approach based on when the loss occurs.

Loss Occurs When Children Are Young

For these clients, the focus is on long-term planning. Planners should advise them to use the advantageous tax filing statuses for as long as possible. Allocate life insurance proceeds into parent-owned 529 plans and retirement accounts. Funds in 401(k)s and IRAs are not reportable assets on the FAFSA, making them a powerful option for sheltering assets while rebuilding the surviving spouse’s financial security.

Loss Occurs When Children Are in High School

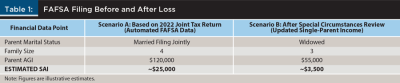

This is a time-critical crisis scenario where the planner’s tactical guidance is paramount. The goal is to execute the two-step FAFSA process flawlessly. The impact of a successful PJ review cannot be overstated, as table 1 illustrates.

As shown, the automated FAFSA data (scenario A) would result in a high SAI figure, rendering the student ineligible for most need-based aid. Following a successful PJ review, however, which reflects the loss of one income (scenario B), the SAI plummets, indicating significant financial need and unlocking eligibility for Pell Grants, institutional grants, and subsidized loans.

Loss Occurs When Children Are Attending College

It’s crisis management in this case. The first call must be to the college’s financial aid office to initiate a PJ review for the current and all subsequent academic years. This is also the time to facilitate a candid family conversation about cost-mitigation strategies to ensure the student can stay enrolled and complete their degree.

Cost-Mitigation Strategies

For “Recalibrate” and “Rebuild” scenarios, reducing the overall COA is essential. This requires a multi-pronged approach that goes beyond simply securing aid.

Scholarships and merit aid. Planners should guide clients to pursue external funding beyond need-based aid. This includes targeted scholarships for students who have lost a parent (e.g., from organizations like the American Legion) and merit-based aid from colleges. Merit scholarships, awarded for academic achievement, act as a direct tuition discount and can make more expensive universities surprisingly affordable.

Student contributions. Planners should encourage a conversation about the students’ contributions, positioning it as an empowering investment in their own future. A part-time job or federal work-study can help cover indirect costs, such as books and personal expenses, thereby reducing the overall loan burden. Additionally, students can assume a reasonable amount of Federal Direct Student Loans. This is often preferable to the surviving parent taking on high-interest Parent PLUS loan debt, as it allows the student to share in the responsibility for their education while protecting the parent’s financial recovery.

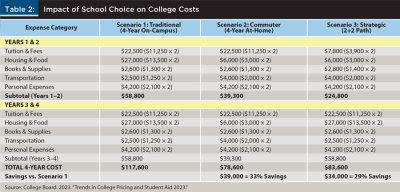

School and housing choices. Finally, the single most impactful cost-mitigation decision is often where the student attends college and where they live. Table 2, based on national averages from the College Board, quantifies the significance of this choice.

The most dramatic savings come from living at home. Compare scenario 1 and scenario 2: a 33 percent cost reduction, nearly $40,000 over four years. For a “Rebuild” situation, this may be the only viable path.

The 2+2 path—two years at community college, two years at a university—offers over $14,000 in up-front savings during those critical first two years when cash flow may be tightest. For “Recalibrate” situations, this presents a powerful middle ground: significant up-front savings while preserving the traditional on-campus experience for the final two years.

It’s essential to view these choices not as downgrades, but as informed, empowering financial decisions. The student still gets a bachelor’s degree. The diploma doesn’t indicate where someone completed the first two years. And the family avoids crippling debt.

Conclusion

Guiding a widowed client through college-funding complexities is profound work that transcends portfolio management. It requires technical mastery of an evolving aid system combined with deep empathy for a family navigating unimaginable loss.

These conversations are hard. You’re discussing the future when clients are still processing the present. But by mastering these nuances and applying them proactively, you provide immense tangible value. You cement your role not just as a financial adviser but as an indispensable partner for the entire family.

When you raise this topic proactively—when you demonstrate that you’ve thought through their situation and have a concrete plan forward—you show that their family’s future, while irrevocably changed, can still be bright.